Walpert v. Jaffrey

Walpert v. Jaffrey

2016 WL 11271873 (S.D.N.Y. 2016)

August 17, 2016

Pitman, Henry, United States Magistrate Judge

Summary

The court found that the plaintiff's records included ESI, such as emails and documents, which were important to the court's assessment of the reasonableness of the work. The court noted that the plaintiff's decision to change counsel in the midst of litigation led to redundancies, and that both firms had overstaffed the matter. The court also found that the 1,145.6 hours worked by the two firms was clearly excessive for the amount of work required by the case.

GARY WALPERT, Plaintiff,

v.

SYED JAFFREY, et al. Defendants

v.

SYED JAFFREY, et al. Defendants

13 Civ. 5006 (PGG)(HBP)

United States District Court, S.D. New York

Filed August 17, 2016

Counsel

Blair Courtney Fensterstock, Evan Steele Fensterstock, Fensterstock & Partners LLP, New York City, NY, for Plaintiff.Deborah J. Denenberg, Gallo Vitucci Klar LLP, New York, NY, for Defendants.

Pitman, Henry, United States Magistrate Judge

REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION

*1 TO THE HONORABLE PAUL G. GARDEPHE, United States District Judge,

I. Introduction

Plaintiff Gary Walpert commenced this action against defendants Syed Jaffrey and Wingate Capital Inc., also known as Wingate Capital New York (“Wingate”), asserting claims for (1) breach of contract, (2) quantum meruit, (3) unjust enrichment, (4) violations of New York Labor Law (“NYLL”) § 193and (5) conversion (Amended Complaint, dated Dec. 13, 2013 (Docket Item (“D.I.”) 19) (Am. Compl.”)).[1] During the course of discovery, defendants “engaged in a variety of misconduct which appears to have been calculated to derail this litigation and frustrate any judgment that Plaintiff might obtain.” Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 124. Defendants’ misconduct included (1) repeatedly failing to pay their counsel’s fees, causing their first two attorneys to move to withdraw; (2) “refusing to obey four separate orders issued by this Court to retain counsel by a specific date”; (3) defendant Jaffrey’s leaving the country less than two weeks prior to his scheduled deposition for an indefinite period of time due to an expired visa and without informing plaintiff of the severity of his immigration issues and (4) Jaffrey’s selling his New Jersey residence and its contents four days before he left the United States in an apparent attempt to frustrate plaintiff’s ability to recover any judgment against him. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 124-27. Accordingly, on August 28, 2015, Judge Gardephe entered a default judgment against defendants on all five claims set forth in plaintiff’s amended complaint, struck defendants’ Answer and referred the matter to me to conduct an inquest on damages concerning plaintiff’s claims and to determine whether Wingate is entitled to an offset based on its unjust enrichment counterclaim. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 129, 137.

On September 22, 2015, I issued a scheduling order directing plaintiff to serve and file his proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law by November 23, 2015 and defendants to serve and file their proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law by December 23, 2015 (Scheduling Order, dated Sept. 22, 2015 (D.I. 81)). Plaintiff filed his submissions on November 23, 2015 (Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, filed Nov. 23, 2015 (D.I. 82) (“Pl. PFFCL”); Affidavit of Blair C. Fensterstock in Support of Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, dated Nov. 16, 2015 (D.I. 83) (“Fensterstock Aff.”); Affidavit of Gary Walpert in Support of Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, dated Nov. 19, 2015 (D.I. 84) (“Walpert Aff.”)). On December 15, 2015, I granted defendants’ request to extend their deadline to respond thirty days to January 23, 2016 (Memo Endorsement, dated Dec. 15, 2015 (D.I. 88)). On January 25, 2016, defendants submitted their proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law (Defendants’ Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, filed Jan. 25, 2016 (D.I. 89) (“Defs. PFFCL”)).[2]

*2 After having considered the parties’ submissions, for the reasons set forth below, I respectfully recommend that judgment be entered against defendants in the amount of $5,972,474.72.

II. Findings of Fact

1. Plaintiff, a resident of Massachusetts, is a practicing attorney with over 40 years of experience who received a J.D. from Harvard Law School and a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 6, 12;[3] Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 1-4).

2. Plaintiff has previously worked as a partner at the law firms of K&L Gates LLP, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale & Dorr LLP (“Wilmer Hale”) and Fish & Richardson P.C. and specializes in intellectual property law as well as transactional law relating to technology (Am. Compl., ¶ 12; Walpert Aff., ¶ 6).

3. From 2010 to 2013, plaintiff worked part-time as Of Counsel at Byrne Poh, LLP (“Byrne Poh”), where his standard hourly rate was $700 (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 7, 27).

4. Defendant Jaffrey, a resident of New Jersey, is the Chief Executive Officer of defendant Wingate, a Delaware corporation doing business in New York with its principal place of business in New York, New York (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 7-8).

5. Defendants are in the business of creating, managing and operating private equity funds and other investment vehicles (Am. Compl., ¶ 10).

6. At all times relevant to this action, Jaffrey had exclusive and complete domination and control over Wingate such that “Wingate was at all times material to this matter, a corporate instrumentality used for the benefit of Jaffrey” (Am. Compl., ¶ 31).

7. Jaffrey intermingled Wingate’s assets and business affairs with his own assets and business affairs, kept Wingate undercapitalized, disregarded Wingate’s corporate form and failed to abide by corporate formalities (Am. Compl., ¶ 31(a)).

8. “Wingate was never intended to have and never had any true existence as a limited corporation” (Am. Compl., ¶ 31(b)).

9. Plaintiff met defendant Jaffrey in 2006 or 2007 when Jaffrey was a client of Wilmer Hale. At that time, Jaffrey retained plaintiff to perform work on issues related to the intellectual property of Delta Search Labs (“Delta Search”), a company Jaffrey controlled (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 8-9; Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 8).

10. In 2010, Jaffrey recruited plaintiff to work on a private equity start-up fund that Jaffrey planned on creating (Am. Compl., ¶ 13; Walpert Aff., ¶ 10).

11. Thereafter, in or about July 2010, plaintiff and Wingate entered into an employment contract (the “Agreement”) pursuant to which plaintiff was employed as “Executive Vice President and General Counsel” of Wingate (Am. Compl., ¶ 14; Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 1).

12. The Agreement provides that “[t]he term of this Agreement and the Period of [plaintiff’s] employment under this Agreement shall begin as of [June 11, 2010] and shall continue for a period of thirty-six (36) full calendar months, and shall continue thereafter until terminated in accordance with article 6 [of the Agreement]” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 2(a)).

*3 13. The Agreement provides that plaintiff “may continue to practice law for outside clients as Of Counsel to a private law firm of his choosing, as long as such representation does not unreasonably interfere with, or create a conflict of interest with respect to, the performance of his duties for [Wingate]” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 3(b)).

14. Pursuant to that provision of the Agreement, plaintiff worked part-time for Byrne Poh for three to five hours per week for the first eight to ten months he worked for Wingate and “a little more thereafter,” when there was less work from Wingate (Walpert Aff., ¶ 27).

15. The Agreement provides that plaintiff’s base salary would be $900,000 per year and that plaintiff was to be payed “not less often than on a pro rate basis, monthly” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 4(a)).

16. During the course of his employment for Wingate, despite repeated demands for payment, plaintiff was not paid for “over thirty-five (35) months” and only received one $50,000 payment pursuant to the Agreement in 2012 (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 25-29; Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 28-31; Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 14 (“Hearing Tr.”), 41:10-20).[4]

17. Plaintiff also received two other payments from Jaffrey -- a $15,000 “gift” from Jaffrey and a $500 check to reimburse plaintiff for the costs of setting up a virtual office (Hearing Tr., 42:16-44:13).

18. Plaintiff also worked on personal matters for Jaffrey and his wife, as well as other companies controlled by Jaffrey; Jaffrey accepted this work and knew that plaintiff expected to be paid for this work (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 19-20, 38-42; Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 19-26).

19. During the course of his employment with Wingate, plaintiff furnished his office with several personal items, including a teak desk, a teak credenza, a leather executive chair, a Tiffany picture frame, wall art and other accessories (the “Office Furnishings”). Plaintiff also kept several boxes of personal documents and work product in his Wingate office (Am. Compl., ¶ 22; Walpert Aff., ¶ 33).

20. Defendants removed the Office Furnishings from Wingate’s executive offices to another location under their dominion and control (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 30, 60-64; Walpert Aff., ¶ 34).

21. In support of his request for attorneys’ fees, plaintiff has submitted invoices and time records he received from Fensterstock & Partners LLP (the “Fensterstock firm”), his current counsel and Pryor Cashman LLP (“Pryor Cashman”), the first firm to represent him in this matter (Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 2; Walpert Aff., ¶ 35 & Ex. E).

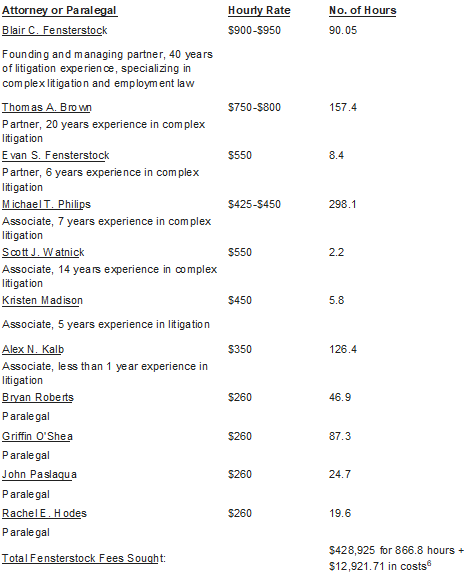

22. In addition to its billing records, the Fensterstock firm has submitted the affidavit of Blair C. Fensterstock, the founding and managing partner of the Fensterstock firm, which sets forth the qualifications for the individuals who worked on this matter at the Fensterstock firm. As detailed in the affidavit and the Fensterstock firm’s billing records, plaintiff seeks attorneys’ fees for the Fensterstock firm as follows:

(Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 1-42; Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 34).

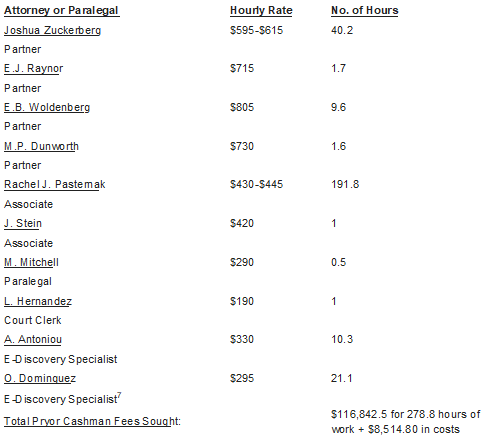

23. Plaintiff also seeks fees for Pryor Cashman as follows:

(Walpert Aff., Ex. E).

III. Conclusions of Law

24. “ ‘[W]hile a party’s default is deemed to constitute a concession of all well pleaded allegations of liability, it is not considered an admission of damages.’ ” Renaissance Search Partners v. Renaissance Ltd. LLC, 12 Civ. 5638 (DLC), 2014 WL 4928945 at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 1, 2014) (Cote, D.J.), quoting Cement & Concrete Workers Dist. Council Welfare Fund v. Metro Found. Contractors Inc., 699 F.3d 230, 234 (2d Cir. 2012).

25. Therefore, even where, as here, defendants have defaulted, the court must “conduct an inquiry in order to ascertain the amount of damages with reasonable certainty.” Credit Lyonnais Secs. (USA), Inc. v. Alcantara, 183 F.3d 151, 155 (2d Cir. 1999).

26. To determine damages, a court may rely on detailed affidavits and documentary evidence in lieu of an evidentiary hearing. Action S.A. v. Marc Rich & Co., Inc., 951 F.2d 504, 508 (2d Cir. 1991); Trustees of Mason Tenders District Council Welfare Fund, Pension Fund, Annuity Fund & Training Program Fund v. Stevenson Contracting Corp., 05 Civ. 5546 (GBD)(DF), 2008 WL 3155122 at *4 (S.D.N.Y. June 19, 2008) (Freeman, M.J.) (Report & Recommendation), adopted, 2008 WL 2940517 (S.D.N.Y. July 29, 2008) (Daniels, D.J.); see Fed.R.Civ.P. 55(b)(2)(B) (“The court mayconduct hearings or make referrals ... when, to enter or effectuate judgment, it needs to ... determine the amount of damages.” (emphasis added)).

27. Accordingly, I rely on the evidentiary submissions made by both parties and deem such evidence, except where it is inconsistent or disputed, to be correct.

A. Plaintiff’s Claim for Breach of Contract

28. In his Memorandum Opinion and Order granting plaintiff’s motion for default, Judge Gardephe found that both defendants were liable on plaintiff’s breach-of-contract claim for breaching the Agreement. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 130-34.

29. Under New York law, “ ‘the normal measures of damages for breach of contract is expectation damages ....’ ” In re: Residential Capital, LLC, 533 B.R. 379, 407 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2015) (Glenn, B.J.), quoting McKinley Allsopp, Inc. v. Jetborne Int’l, Inc., 89 Civ. 1489 (PNL), 1990 WL 138959 at *8 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 19, 1990) (Leval, D.J.). “Expectation damages ... constitute ‘the amount necessary to put plaintiff in as good a position as if defendant had fulfilled the contract.’ ” In re: Residential Capital, LLC, supra, 533 B.R. at 407, quoting Wechsler v. Hunt Health Sys., Ltd., 330 F. Supp. 2d 383, 425 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (Leisure, D.J.).

30. By its terms, the Agreement entitles plaintiff to $2,700,000 in base salary for a three-year term running from June 11, 2010 to June 10, 2013 (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, §§ 2, 4(a)).

31. Plaintiff has only received one payment of $50,000 pursuant to the Agreement (Am. Compl., ¶¶ 25-29; Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 28-32; Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 14 (“Hearing Tr.”), 41:10-20), which would appear to dictate that he is entitled to $2,650,000 in damages on his breach-of-contract claim. However, in both his inquest submissions and his amended complaint, plaintiff seeks only $2,612,500 with respect to his breach-of-contract claim (Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 19; Am. Compl., ¶ 37). Pursuant to Rule 54(c), “[a] default judgment must not differ in kind from, or exceed in amount, what is demanded in the pleadings.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 54(c). Accordingly, I conclude that plaintiff is entitled to $2,612,500 on his breach-of-contract claim and recommend an award in that amount.

B. Plaintiff’s Claims for Quantum Meruit & Unjust Enrichment

*5 32. Under New York law, quantum meruit and unjust enrichment claims are analyzed together as a single quasi-contract claim. Mid-Hudson Catskill Rural Migrant Ministry, Inc. v. Fine Host Corp., 418 F.3d 168, 175 (2d Cir. 2005). “In order to recover in quantum meruit under New York law, a claimant must establish ‘(1) the performance of services in good faith, (2) the acceptance of the services by the person to whom they are rendered, (3) an expectation of compensation therefor, and (4) the reasonable value of the services.’ ” Mid-Hudson Catskill Rural Migrant Ministry, Inc. v. Fine Host Corp., supra, 418 F.3d at 175, quoting Revson v. Cinque & Cinque, P.C., 221 F.3d 59, 69 (2d Cir. 2000)). Additionally, “New York law does not permit recovery in quantum meruit ... if the parties have a valid, enforceable contract that governs the same subject matter as the quantum meruit claim.” Mid-Hudson Catskill Rural Migrant Ministry, Inc. v. Fine Host Corp., supra, 418 F.3d at 175.

33. Plaintiff seeks quasi-contract damages for the work he performed for defendants that fell outside of the scope of the Agreement (Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 20-23). Specifically, because the Agreement covers only plaintiff’s work for Wingate (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 3(a)), plaintiff seeks damages for work he claims he did outside of the Agreement for Jaffrey and his wife and various other companies plaintiff alleges Jaffrey controlled, which include Delta Search, Ovalia Resorts and Collingwood Investment LLC (“Collingwood”) (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 20-25; Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 20-23). In total, plaintiff seeks $449,400 for “approximately 642 hours” of legal services he claims he provided to Jaffrey outside of the Agreement, as well $29,519.99 in expenses plaintiff alleges he incurred relating to the same (Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 22-23).

34. In support of his claim that he provided approximately 642 hours of legal services outside of the Agreement, plaintiff relies on his own estimation of the hours he worked on various projects, which are based on his “recollection using whatever entries were contemporaneously made in [his] personal diaries, as all other business records were located in, and removed from, [his] office under Jaffrey’s control” (Walpert Aff., ¶ 22). Plaintiff’s submissions include two charts which list the specific dates on which plaintiff believes, based on his own records and recollection, he did work for Jaffrey that was outside of the scope of the Agreement. The first chart relates to work plaintiff alleges he did for Delta Search and includes 56 separate dates on which “meetings or conversations” occurred (Walpert Aff., ¶ 22). The second chart relates to all other matters on which plaintiff claims he worked and includes 26 separate dates on which meetings relating to that work occurred (Walpert Aff., ¶ 25). These charts, and the date entries contained therein, provide only limited support for the hours plaintiff is claiming for work on matters outside the scope of the Agreement; the charts do not provide any information regarding the number of hours plaintiff worked on the dates listed in the charts, and many of the specific date entries are blank and do not contain any explanation as to the type of work done by plaintiff on those dates (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 22, 25).

35. Plaintiff also submitted his “contemporaneous journal records,” which are handwritten calendar entries, to corroborate the hours he claims he worked (Walpert Aff., ¶ 25 & Ex. B[8]). However, these handwritten records provide only limited support for plaintiff’s estimates. For instance, these journal entries do not state the number of hours worked on any specific matter. Further, these records are generally vague as to what specific work plaintiff was doing on the dates listed and whether that work related to his duties under the Agreement or fell outside the Agreement.[9] Moreover, these handwritten records only provide this limited support for 35 of the 56 dates on which plaintiff purportedly did work relating to Delta Search and 17 of the 26 dates on which plaintiff purportedly did other work that fell outside of the scope of his duties under the Agreement; the journal entries for the remaining dates do not indicate that any work was done on those dates.

*6 36. Additionally, although plaintiff claims that his work for various other companies allegedly controlled by Jaffrey, such as Delta Search, Ovalia Resorts and Collingwood, was not related to his contractual duties, plaintiff also states in his affidavit that his “work for Wingate included, primarily, the formation of a limited liability company, USDFM, and work regarding otherinvestment opportunities” (Walpert Aff., ¶ 16 (emphasis added)). Further, despite the fact that he is now seeking quasi-contract damages for work relating to Collingwood, plaintiff testified at the default hearing that “the primary work [he did for Wingate] was the formation of the LLCs, USDFM and Collingwood” and that “there was work relating to other investment targets that Mr. Jaffrey came up with” (Hearing Tr., 26:12-19; see also Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 7 (“Plaintiff’s primary work for Wingate was the formation of two limited liability companies and other investment opportunities, including USDFM and Collingwood.”)). Because it appears that some of this work may have been done pursuant to plaintiff’s duties under the Agreement, plaintiff may not be able to recover these damages on his quasi-contract claim. Mid-Hudson Catskill Rural Migrant Ministry, Inc. v. Fine Host Corp., supra, 418 F.3d at 175.

37. With respect to the work done for Delta Search, defendants argue that plaintiff is not entitled to any quasi-contract damages related to this work because “[p]laintiff was hired to do patent work on behalf [of] Delta Search Labs in his capacity as a patent attorney with Byrne Poh” (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 14). In support of this argument, defendants cite to Jaffrey’s affidavit, which states that Delta Search Labs was a client of Byrne Poe and that “Walpert represented them, and Byrne Poh invoiced Delta for its services” (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 14 & Ex. C, ¶ 5). Further, although plaintiff does not state that his work for Delta Search was done as “Of Counsel” to Byrne Poh, he does state that he continued to work part-time for Byrne Poh during his employment with defendants and that Byrne Poh represented Delta Search Labs on some matters (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 26-27). Accordingly, some, if not all, of the work plaintiff claims he did for Delta Search may have been work he undertook as part of his part-time role with Byrne Poh, and it therefore may be the case that plaintiff did not actually have “an expectation of compensation” directly from Jaffrey for this work as is required to recover damages on a quasi-contract claim. Mid-Hudson Catskill Rural Migrant Ministry, Inc. v. Fine Host Corp., supra, 418 F.3d at 175.

38. Defendants also dispute that plaintiff did any work for Ovalia Resorts or Collingwood, citing Jaffrey’s affidavit, in which he states that plaintiff was not hired or retained to do any work for Ovalia Resorts or Collingwood (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 12).

39. In addition to seeking damages for the legal work he performed for defendants outside of his duties pursuant to the Agreement, plaintiff also seeks additional quasi-contract damages in the amount of $29,519.99 in expenses he claims he incurred while working on these outside matters (Walpert Aff., ¶ 26). These expenses are split between two categories.

40. The first category is $11,113.02 that plaintiff claims he incurred “related to travel and other expenses for [his] work with Delta Search Labs” (Walpert Aff., ¶ 26). In support of this category of expenses, plaintiff has submitted a handwritten expense sheet that includes the heading “DISB” (Walpert Aff., Ex. C). When added together, the various items on this sheet amount to $11,075.60, not the $11,113.02 listed in plaintiff’s affidavit. Further, defendants dispute these damages, relying on Jaffrey’s affidavit, which states that “at no time was plaintiff expected or requested to go [on business trips]” and that he never received “a single invoice to support these alleged business expenses nor has plaintiff ever submitted a supporting invoice to date” (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶¶ 18-19).

41. The second category of expenses plaintiff seeks relates to expenses Byrne Poh incurred while representing Delta Search Labs (Walpert Aff., ¶ 26). Specifically, plaintiff states that Byrne Poh was representing Delta Search Labs and that, when Delta Search Labs failed to pay fees it owed to Byrne Poh, Byrne Poh withheld the amount of these fees from plaintiff’s compensation from Byrne Poh (Walpert Aff., ¶ 26).[10] In support of this claim, plaintiff has submitted what he calls “a record of expenses Delta Search Labs accrued while being represented by Byrne Poh” (Walpert Aff., ¶ 26 & Ex. D). In this record, which appears to be a billing statement, the “Total Expenses” are listed as $40,932.97, and the $18,046.97 plaintiff claims he was obliged to cover is listed as “Funds Currently Being held for Delta” (Walpert Aff., Ex. D).

*7 42. Plaintiff does not offer any explanation, however, as to why money withheld from him by Byrne Poh is chargeable to defendants or why he believes it is recoverable on his quasi-contract claim.

43. In sum, plaintiff’s evidence pursuant to this claim does not adequately establish plaintiff’s entitlement to the damages he seeks on his quasi-contract claims. Further, the submissions from both sides demonstrate that there are factual disputes as to many of the damages for which plaintiff has provided some support. Accordingly, I conclude that the current evidentiary record is insufficient to award any damages on plaintiff’s quasi-contract claims.

C. Plaintiff’s NYLL Claim

44. “New York Labor Law § 193(1) prohibits employers from making ‘any deduction from the wages of an employee’ with certain exceptions that are not applicable here.” Chenensky v. N.Y. Life Ins. Co., 07 Civ. 11504 (WHP), 2012 WL 234374 at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 10, 2012) (Pauley, D.J.), quoting N.Y. Labor L. § 193(1)). In his August 28, 2015 Memorandum Opinion and Order, Judge Gardephe found that defendants are liable under NYLL § 193(1) because they failed to make payments owed to plaintiff pursuant to the Agreement. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 135(“Defendants Jaffrey and Wingate are liable on Plaintiff’s New York Labor Law claim.”).

45. Accordingly, plaintiff seeks liquidated damages pursuant to NYLL § 198(1-a) in the amount of 100% of the $2,612,500 that he claims he is owe pursuant to the Agreement (Pl. PFFCL ¶¶ 24-26).

46. NYLL § 198(1-a) provides, in pertinent part:

In any action instituted in the courts upon a wage claim by an employee ... in which the employee prevails, the court shall allow such employee to recover the full amount of any underpayment, all reasonable attorney’s fees, prejudgment interest as required under the civil practice law and rules, and, unless the employer proves a good faith basis to believe that its underpayment of wages was in compliance with the law, an additional amount as liquidated damages equal to one hundred percent of the total amount of the wages found to be due ....

47. Defendants argue, however, that plaintiff should not receive liquidated damages because Judge Gardephe never determined that defendants acted willfully (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 6). Defendants’ argument ignores the fact that although liquidated damages were formerly imposed only where the employee demonstrated that an employer’s violations was willful, “[e]ffective November 24, 2009, New York law ... shifted the burden of proof to the employer” to prove a good faith basis for believing that its underpayment of wages complied with the law. Galeana v. Lemongrass on Broadway Corp., 10 Civ. 7270(GBD)(MHD), 2014 WL 1364493 at *8 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 4, 2014)(Daniels, D.J.); Hart v. Rick’s Cabaret Int’l, Inc., 967 F. Supp. 2d 901, 937 (S.D.N.Y. 2013) (Engelmeyer, D.J.) (“[U]nder the NYLL after November 24, 2009, a finding of good faith is an affirmative defense to liquidated damages.”). Here, Judge Gardephe struck defendants’ Answer. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 137. Accordingly, defendants cannot assert a good faith defense to avoid liability for liquidated damages.

48. The NYLL permits employees to recover as liquidated damages 25% of the total unpaid wages owed prior to and including April 8, 2011 and 100% of the total unpaid wages owed thereafter. N.Y. Labor L. § 663(1); accordAlvarez v. 215 N. Ave. Corp., 13 Civ. 7049 (NSR)(PED), 2015 WL 3855285 at *3 (S.D.N.Y. June 19, 2015) (Román, D.J.) (“Prior to April 9[,] 2011[,] a plaintiff was entitled to liquidated damages in the amount of 25 percent of his actual damages. As of April 9, 2011, these state damages are set at 100 percent of unpaid wages.” (citations omitted)).

*8 49. Here, plaintiff worked for 43 weeks for Wingate prior to April 9, 2011 and was unpaid that entire time (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 12, 29-30). During that time, he was owed $744,230.77 ($17,307.69 weekly salary[11] × 43 weeks). 25 percent of $744,230.77 is $186,057.69. For the remaining time plaintiff worked for Wingate, he claims he was underpaid $1,868,269.23 ($2,612,500 - $744,230.77). 100 percent of $1,868,269.23 is $1,868,269.23. Accordingly, I conclude that plaintiff is owed $2,054,326.92 ($1,868,269.23 + $186,057.69) in NYLL liquidated damages.

D. Plaintiff’s Conversion Claim

50. “A plaintiff who prevails on a conversion claim may recover the value of the property at the time and place of conversion, plus interest.” Seifts v. Consumer Health Solutions LLC, 61 F. Supp. 3d 306, 319 (S.D.N.Y. 2014)(Ramos, D.J.), quoting Wells Fargo Bank, NA. v. Nat’l Gasoline, Inc., No. 10-VC-1762, 2013 WL 1822288 at *10 (E.D.N.Y. Apr. 30, 2013).

51. Plaintiff seeks $26,600 in damages for various items that were removed from the office defendants provided for him when defendants were evicted from that office space (Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 27-30). Specifically, plaintiff seeks $6,000 for an eight-foot teak desk, $3,000 for a teak credenza, $5,000 for a high-back leather executive chair, $800 for an art print, $800 for two Venetian paintings, $1,000 for a Plycraft chair and $10,000 for thirty boxes of books, client materials, notes, forms and other accessories (Walpert Aff., ¶¶ 33-34).

52. Plaintiff’s basis for the value of these items are his own estimates, which plaintiff characterizes as “uncontested” (Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 29; Walpert Aff., ¶ 33-34). 53. Defendants dispute plaintiff’s estimates, however, characterizing them as “unsubstantiated and fictitious” because they are based on plaintiff’s “self-serving Affidavit” and are not corroborated by receipts, invoices, appraisals or “even a photograph depicting this furniture” (Defs. PFFCL, ¶¶ 16, 18).[12] Jaffrey also states that he has “no knowledge [of] photographs or other documentation of the personal property that was allegedly lost or misplaced” (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 20).

*9 54. Because defendants dispute the value of these items, I conclude that the current evidentiary record is insufficient to award any compensatory damages on plaintiff’s conversion claim.

55. Plaintiff also seeks $500,000 in punitive damages on his conversion claim (Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 31-32).

56. Under New York law, a plaintiff may recover punitive damages on a conversion claim where “the conversion was accomplished by malice or reckless or willful disregard of the plaintiff’s right.” Bazignan v. Team Castle Hill Corp., 13 Civ. 8382 (PAC), 2015 WL 1000034 at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 5, 2015) (Crotty, D.J.), quoting Doo Nam Yang v. ACBL Corp., 427 F. Supp. 2d 327, 341-42 (S.D.N.Y.2005) (Sand, D.J.).

57. Plaintiff argues that he is entitled to punitive damages because Jaffrey “knowingly caused [his] property to be removed from Wingate’s offices without informing [plaintiff]” (Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 32). In support of this argument, plaintiff cites to his default hearing testimony, in which he stated that he asked Jaffrey what happened to his property and Jaffrey stated that the property was “gone and [said] something flippant like he needed a new desk anyhow” (Hearing Tr., 48:15-18).

58. Defendants, however, argue that plaintiff should not be awarded punitive damages because he did not seek them in the complaint (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 21; see also Am. Compl., ¶ 64 (seeking damages “believed to be ... no less than $20,000, plus interest, costs, and attorneys’ fees” on the conversion claim, but no mention of punitive damages)).

59. Because plaintiff did not seek punitive damages in his amended complaint, plaintiff is not entitled to punitive damages. Fed.R.Civ.P. 54 (“A default judgment must not differ in kind from, or exceed in amount, what is demanded in the pleadings.”). Accordingly, I recommend that plaintiff be awarded no punitive damages on his conversion claim.

E. Defendants’ Unjust Enrichment Counterclaim

60. Wingate also has asserted an unjust enrichment counterclaim against plaintiff, alleging that plaintiff used his Wingate office space to “perform[ ] services for persons and/or companies unrelated to Jaffrey, Wingate or USDFM, including work for clients of the law firm Byrne Poh LLP, with whom, upon information and belief, Walpert had an ‘of counsel’ relationship” and that “Walpert knew that Wingate was paying to occupy and use the Office Suite, and that Wingate expected Walpert to pay for his share of the costs associated with Walpert’s occupancy and use of an office” (Answer to Amended Complaint with Counterclaim, dated Jan. 21, 2014 (D.I. 21), ¶¶ 74-86). In support of its counterclaim, Wingate relies on Section 3(b) of the Agreement, which provides that, if plaintiff “conduct[s] his law practice at [Wingate’s] offices and ... use[s] such staff assistance and equipment as may be needed to do so, ... [plaintiff] agrees to pay [Wingate] a facilities fee of at least $2000 a month, no later than the 10th of each month, to cover the cost thereof” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 3(b)). In his August 28, 2015 Memorandum Opinion and Order, Judge Gardephe held that the factual record for Wingate’s counterclaim was too incomplete to conclude whether it constitutes a meritorious defense and referred the counterclaim to me for further inquiry, stating that “[a]fter [D]efendant [Wingate has] been given an opportunity to flesh out the factual foundation for [the] counterclaim, the Magistrate Judge will decide whether Plaintiff’s recovery should be reduced to account for damages owed on Wingate’s counterclaim.” Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 137 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted; alterations in original).

*10 61. Despite having been given the chance to further flesh out the factual foundation for Wingate’s counterclaim, defendants do not address the unjust enrichment counterclaim in their proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law.

62. Further, because plaintiff’s liability on Wingate’s counter-claim remains an open issue, there is no basis for an offset on the record before me.

F. Pre-Judgment Interest

63. Plaintiff seeks pre-judgment interest on his contract/NYLL claims in the amount of $779,625.

64. The NYLL provides that, “[i]n any action instituted in the courts upon a wage claim by an employee ... in which the employee prevails, the court shall allow such employee to recover ... prejudgment interest as required under the civil practice law and rules.” N.Y. Labor L. § 198(1-a). Additionally, § 5001(a) of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules provides that “[i]nterest shall be recovered upon a sum awarded because of a breach of performance of a contract ....” N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5001(a).

65. The New York statutory interest rate is 9 percent. N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5004; see also Marfia v. T.C. Ziraat Bankasi, 147 F.3d 83, 90 (2d Cir. 1998)(citations omitted) (“New York courts have held that in a breach of contract action of this sort prejudgment interest must be calculated on a simple interest basis at the statutory rate of nine percent.”), modified on othergrounds, Baron v. Port Auth. of N.Y. & N.J., 271 F.3d 81 (2d Cir. 2001).

66. Under New York law,

[i]nterest shall be computed from the earliest ascertainable date the cause of action existed, except that interest upon damages incurred thereafter shall be computed from the date incurred. Where such damages were incurred at various times, interest shall be computed upon each item for the date it was incurred or upon all of the damages from a single reasonable intermediate date.”

N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5001(b).

67. Further, plaintiff’s recovery of liquidated damages under the NYLL does not preclude the recovery of prejudgment interest “[b]ecause state liquidated damages are punitive in nature[;] a plaintiff awarded this form of damages may also recover pre-judgment interest.” Galeana v. Lemongrass on Broadway Corp., supra, 2014 WL 1364493 at *11.

68. The Agreement had a three-year term that ran from June 11, 2010 through June 10, 2013 (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 2). The Agreement further provides that plaintiff’s salary was to be paid “no less often than on a pro rate basis, monthly” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 4(a)).

69. Accordingly, plaintiff’s contractual damages began to accrue, at the latest, on July 11, 2010 -- one month after the date on which the term of the contract commenced -- and the latest date on which the final installment of plaintiff’s contractual damages accrued is July 10, 2013. A reasonable intermediary date between July 11, 2010 and July 10, 2013 is January 11, 2012 -- 18 months after July 11, 2010 and 18 months before July 10, 2013.

70. Accordingly, I conclude that plaintiff is entitled to $1,091,237.66 in pre-judgment interest through August 31, 2016 and interest at the rate of nine percent thereafter.

G. Attorneys’ Fees and Costs

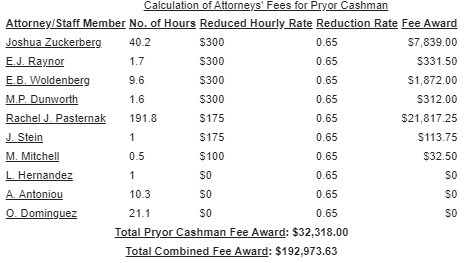

71. Plaintiff also seeks $441,846.71 in attorneys’ fees and costs for work done by the Fensterstock firm and $125,357.30 in fees and costs for work done by Pryor Cashman (Pl. PFFCL, ¶¶ 33-35).

*11 72. The NYLL provides that a successful plaintiff may recover attorneys’ fees. N.Y. Labor L. §§ 198(1-a). The Agreement also provides that “all reasonable legal fees paid or incurred by [plaintiff] pursuant to any dispute or question of interpretation relating to this Agreement shall be paid or reimbursed by [Wingate], provided that the dispute or interpretation has been settled by [plaintiff] and [Wingate] or resolved in [plaintiff’s] favor ...” (Walpert Aff., Ex. A, § 16). Further, fee awards “normally include those reasonable out-of-pocket expenses incurred by the attorney and which are normally charged fee-paying clients.” Reichman v. Bonsignore, Brignati & Mazzotta P.C., 818 F.2d 278, 283 (2d Cir. 1987) (citations omitted); accordReiseck v. Universal Commc’ns of Miami, Inc., 06 Civ. 0777 (LGS) (JCF), 2014 WL 5374684 at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 5, 2014) (Francis, M.J.) (Report & Recommendation) (stating that a prevailing plaintiff is entitled to fees and costs pursuant to NYLL § 198), adopted, 2014 WL 5364081 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 22, 2014) (Schofield, D.J.). Accordingly, plaintiff is entitled to attorneys’ fees and costs pursuant to the Agreement and the NYLL.

73. Whether an attorneys’ fee award is reasonable is within the discretion of the court. Melgadejo v. S & D Fruits & Vegetables Inc., 12 Civ. 6852 (RA)(HBP), 2015 WL 10353140 at *23 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 23, 2015) (Pitman, M.J.) (Report & Recommendation), adopted, 2016 WL 554843 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 9, 2016) (Abrams, D.J.) (citation omitted).

74. In determining the amount of reasonable attorneys’ fees, “[b]oth [the Second Circuit] and the Supreme Court have held that the lodestar -- the product of a reasonable hourly rate and the reasonable number of hours required by the case -- creates a ‘presumptively reasonable fee.’ ” Millea v. Metro-North R.R. Co., 658 F.3d 154, 166 (2d Cir. 2011), quoting Arbor Hill Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Ass’n v. Cty. of Albany, 522 F.3d 182, 183 (2d Cir. 2008).

75. The party seeking fees bears the burden of establishing that the hourly rates and number of hours for which compensation is sought are reasonable. Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 434 (1983); accord Cruz v. Local Union No. 3 of Int’l Bhd. of Elec. Workers, 34 F.3d 1148, 1160 (2d Cir. 1994).

76. “[U]nder New York law, courts may award attorney’s fees based on contemporaneous or reconstructed time records.” Schwartz v. Chan, 142 F. Supp. 2d 325, 331 (E.D.N.Y. 2001), citing inter alia Riordan v. Nationwide Mutual Fire Ins. Co., 977 F.2d 47, 53 (2d Cir. 1992). Here, the time records submitted by both law firms satisfy this requirement.

1. Reasonable Hourly Rate

77. The hourly rates used in determining a fee award should be “what a reasonable, paying client would be willing to pay.” Arbor Hill Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Ass’n v. Cty. of Albany, supra, 522 F.3d at 184. This rate should be “in line with those [rates] prevailing in the community for similar services by lawyers of reasonably comparable skill, experience and reputation.” Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 895 n.11 (1984). “[C]ourts should generally use ‘the hourly rates employed in the district in which the reviewing court sits’ in calculating the presumptively reasonable fee.” Arbor Hill Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Ass’n v. Cty. of Albany, supra, 522 F.3d at 192, quoting In re “Agent Orange” Prod. Liab. Litig., 818 F.2d 226, 232 (2d Cir. 1987). In so doing, the court is free to rely on its own familiarity with the prevailing rates in the district. See Miele v. N.Y. State Teamsters Conf. Pension & Ret. Fund, 831 F.2d 407, 409 (2d Cir. 1987). Further, “where appropriate [courts may] employ out-of-district rates in calculating the fee due.” Arbor Hill Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Ass’n v. Cty. of Albany, supra, 522 F.3d at 192-93.

78. As the fee applicant, plaintiff “bears the burden of establishing the reasonableness of the hourly rates requested -- in particular, by producing satisfactory evidence that the requested rates are in line with those prevailing in the community.” Cardoza v. Mango King Farmers Mkt. Corp., No. 14-CV-3314 SJ RER, 2015 WL 5561033 at *14 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 21, 2015) (Report & Recommendation), adopted, 2015 WL 5561180 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 21, 2015), citing Blum v. Stenson, supra, 465 U.S. at 895 n.11.

a. The Fensterstock Firm

*12 79. The Fensterstock firm seeks fees for seven attorneys and four paralegals (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 1-42). However, while the Fensterstock firm has provided the qualifications for its attorneys and paralegals, it has not offered any authority to support the specific rates it seeks.

i. Attorneys

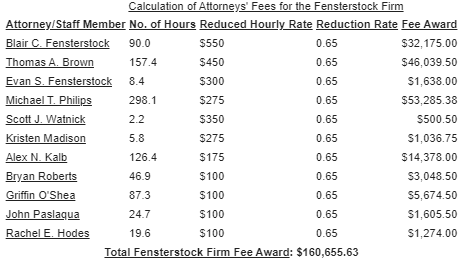

80. Blair C. Fensterstock is the managing partner of the Fensterstock firm with 40 years of litigation experience. Blair C. Fensterstock specializes in complex commercial litigation, including employment law. Blair C. Fensterstock’s billing rate was $900 per hour in 2014 and $950 per hour in 2015 (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 1-4, 10).

81. Thomas A. Brown is a former partner of the Fensterstock firm with over 20 years of complex litigation experience. Brown’s billing rate was $750 per hour in 2014 and $800 per hour in 2015 (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 11, 13).

82. Evan S. Fensterstock is a partner of the Fensterstock firm with over six years of complex litigation experience. His billing rate is $550 per hour (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 14, 16).

83. Michael T. Philips was an associate at the Fensterstock firm during the course of this litigation. Philips has over seven years of complex litigation experience. Philips’ billing rate was $425 per hour in 2014 and $450 per hour in 2015 (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 17, 19).

84. Scott J. Watnick was an associate at the Fensterstock firm during the course of this litigation. Watnik has over 14 years of complex litigation experience. At the Fensterstock firm, Watnik’s billing rate was $550 per hour (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 20, 22).

85. Kristen Madison was an associate at the Fensterstock firm during the course of this litigation. Madison has over five years of complex litigation experience. At the Fensterstock firm, Madison’s billing rate was $450 per hour (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 23, 25).

86. Alex N. Kalb is an associate at the Fensterstock firm. At the time of the filing of plaintiff’s submissions on inquest, Kalb had approximately one year of litigation experience. Kalb’s billing rate is $350 per hour (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 29, 31).

87. The rates the Fensterstock firm seeks for its attorneys are greater than the typical awards given by courts within this district. “In the Southern District of New York, fee rates for experienced attorneys in small firms generally range from $250 to $450 in civil cases.” Watkins v. Smith, 12 Civ. 4635 (DLC), 2015 WL 476867 at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 5, 2015) (Cote, D.J.) (collecting cases).

88. However, for attorneys with extensive employment litigation experience -- i.e., more than fifteen years of litigation experience -- courts within this district have awarded fees at rates between $400 and $600 per hour. See, e.g., Thor 725 8th Ave. LLC v. Goonetilleke, 14 Civ. 4968 (PAE), 2015 WL 8784211 at *10-*11 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 15, 2015) (Engelmeyer, D.J.) (awarding $450 hourly rate for attorney with 26 years of experience), appeals filed, No. 16-212 (2d. Cir. Jan. 21, 2016) and No. 16-139 (2d Cir. Jan. 14, 2016); Guallpa v. N.Y. Pro Signs Inc., 11 Civ. 3133 (LGS)(FM), 2014 WL 2200393 at *9-*10 (S.D.N.Y. May 27, 2014) (Maas, M.J.) (Report & Recommendation) (recommending a rate of $600 per hour for an attorney with 19 years of experience at a “highly regarded” employment law firm), adopted, 2014 WL 4105948 (S.D.N.Y. Aug 18, 2014) (Schofield, D.J.); Kim v. Kum Gang, Inc., 12 Civ. 6344 (MHD), 2014 WL 2514705 at *1-*2 (S.D.N.Y. June 2, 2014) (Dolinger, M.J.) (reducing fee award from $950 to $600 per hour for an “experienced senior litigator” from a large law firm); Torres v. Gristede’s Operating Corp., 04 Civ. 3316 (PAC), 2012 WL 3878144 at *3-*4 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 6, 2012) (Crotty, D.J.) (reducing rate for partner at employment law firm of Outten & Golden with more than 20 years’ experience from $650 per hour to $550 per hour), aff’d, 519 F. App’x 1 (2d Cir. 2013) (summary order); Underdog Trucking, L.L.C. v. Verizon Servs. Corp., 276 F.R.D. 105, 109 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) (Cott, M.J.) (awarding $550 to partner with over forty years experience); Rahman v. The Smith & Wollensky Rest. Grp., Inc., 06 Civ. 6198 (LAK)(JCF), 2009 WL 72441 at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 7, 2009) (Francis, M.J.) (awarding an hourly rate of $535 per hour for the founding partner of New York office for nation’s largest labor and employment law firm and $440 per hour for partner with 20 years experience); see also Scharff v. Cty. of Nassau, CV 10-4208(DRH)(GRB), 2016 WL 3166848 at *5-*6 (E.D.N.Y. May 20, 2016) (Report & Recommendation) (recommending rates of $400 per hour for two attorneys with over 25 years experience, each of whom were “expert trial attorneys with extensive experience before the federal bar”), adopted, 2016 WL 3172798 (E.D.N.Y. June 6, 2016). Accordingly, I recommend that Blair C. Fensterstock’s hourly rate be reduced to $550 and that Thomas A. Brown’s hourly rate be reduced to $450.

*13 89. For experienced attorneys with over ten years of experience, courts in this district generally award between $250 and $400 in employment litigations. See, e.g., Thor 725 8th Ave. LLC v. Goonetilleke, supra, 2015 WL 8784211 at *10-*11 (awarding attorney with 15 years’ experience an hourly rate of $375); Melgadejo v. S & D Fruits & Vegetables Inc., supra, 2015 WL 10353140 at *24 (recommending $350 hourly rate for managing partner of small employment law firm with 11 years of labor and employment experience); Liang Huo v. Go Sushi Go 9th Ave., 13 Civ. 6573 (KBF), 2014 WL 1413532 at *7-*8 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 10, 2014) (Forrest, D.J.) (awarding $350 for employment law litigator with almost 10 years of experience); Wong v. Hunda Glass Corp., 09 Civ. 4402 (RLE), 2010 WL 3452417 at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 1, 2010) (Ellis, M.J.) (“[T]he range of fees in this District for civil rights and employment law litigators with approximately ten years’ of experience is between $250 per hour and $350 per hour.”). Accordingly, I recommend that Scott J. Watnik’s hourly rate be reduced to $350.

90. For experienced attorneys with less than ten years’ experience, courts typically award hourly rates of between $200 and $300. Melgadejo v. S & D Fruits & Vegetables Inc., supra, 2015 WL 10353140 at *24 (recommending $275 hourly rate for attorneys with at least five years of litigation experience); Collado v. Donnycarney Rest. L.L.C., 14 Civ. 3899 (GBD)(HBP), 2015 WL 4737917 at *11 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 10, 2015) (Daniels, D.J.) (same); Alvarez v. 215 N. Ave. Corp., supra, 2015 WL 3855285 at *8(same); Allende v. Unitech Design, Inc., 783 F. Supp. 2d 509, 514 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) (Peck, M.J.) (holding that a rate of $300 for experienced associates “[is] consistent with rates awarded by the courts in other FLSA or similar statutory fee cases” (collecting cases)); see also Herrera v. Tri-State Kitchen & Bath, Inc., No. 14-CV-1695 (ARR)(MDG), 2015 WL 1529653 at *14 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2015) (“Courts have recently recognized that hourly rates range from approximately $200 to $250 for associates with [approximately 7-8 years experience]”); Jemine v. Dennis, 901 F. Supp. 2d 365, 392 (E.D.N.Y. 2012) (awarding a $250 rate for a senior associate with nine years experience in employment law). Accordingly, I recommend that Evan S. Fensterstock’s hourly rate be reduced to $300 and that Kristen Madison and Michael T. Philips’ hourly rates be reduced to $275.

91. Finally, courts in this district generally award rates well below $250 per hour for attorneys with only one year of experience. Gonzalez v. Scalinatella, Inc., 112 F. Supp. 3d 5, 28 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (Dolinger, M.J.) (noting that “[g]enerally, rates in excess of $225.00 per hour are reserved for [wage and hour] litigators with more than three years’ experience” and awarding a $150 hourly rate for a first-year associate and a $175 hourly rate for a second-year associate); see also Agudelo v. E & D LLC, 12 Civ. 960 HB, 2013 WL 1401887 at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 4, 2013) (Baer, D.J.) (stating that the market rate for an attorney with three years’ experience is $200 per hour); Walker v. City of New York, No. 11-CV-314 CBA, 2015 WL 4568305 at *7 (E.D.N.Y. July 28, 2015) (awarding $150 hourly rate for first-year associate). Accordingly, I recommend that Alex N. Kalb’s hourly rate be reduced to $175.

ii. Paralegals

92. Bryan Roberts, Griffin O’Shea, John Paslaqua and Rachel E. Hodes are paralegals who are or were employed by the Fensterstock firm during the course of this litigation. The Fensterstock firm seeks an hourly rate of $260 for each of them (Fensterstock Aff., ¶¶ 26, 28, 32, 34-35, 37-38, 40).

93. An hourly rate of $260 is much higher than what courts in this district generally award for paralegals. See, e.g., Melgadejo v. S & D Fruits & Vegetables Inc., supra, 2015 WL 10353140 at *26 (awarding $90 per hour for paralegals in an employment default); Reiseck v. Universal Commc’ns of Miami, Inc., supra, 2014 WL 5374684 at *6 (awarding hourly rates of $95 to $115 for paralegals); Merino v. Beverage Plus Am. Corp., 10 Civ. 706 (ALC)(RLE), 2012 WL 4468182 at *2-*3 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 25, 2012) (Carter, D.J.) (reducing a requested paralegal rate of $125 to $100 in an FLSA and NYLL case); see also Gunawan v. Sake Sushi Rest., 897 F. Supp. 2d 76, 95 (E.D.N.Y. 2012) (reducing a requested rate of $125 for paralegals to $75). Accordingly, I recommend that Roberts, O’Shea, Paslaqua and Hodes’ hourly rates be reduced to $100.

b. Pryor Cashman

*14 94. Plaintiff also seeks fees for the work done by Pryor Cashman on this litigation (Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 35). Specifically, with respect to the work done by Pryor Cashman, plaintiff seeks fees for six attorneys, one paralegal, two E-Discovery specialists and one “court clerk” (Walpert Aff., Ex. E). However, other than providing their job titles, plaintiff has not provided any explanation of these individuals’ qualifications or any authority to support the rates billed.[13]

95. Joshua Zuckerberg was a partner with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate ranged from $595 to $615 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 5, 48[14]).

96. E.J. Raynor was a partner with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $715 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 5).

97. E.B. Woldenberg was a partner with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $805 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 19).

98. M.P. Dunworth was a partner with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $730 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 19).

99. Rachel J. Pasternak was an associate with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and her billing rate ranged from $430 to $445 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 5, 48).

100. J. Stein was an associate with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $420 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 20).

101. M. Mitchell was a paralegal with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $290 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 11).

102. L. Hernandez was a court clerk with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $190 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 20).

103. A. Antoniou was an E-Discovery Specialist with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $330 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 38).

104. O. Dominguez was an E-Discovery Specialist with Pryor Cashman during the course of this litigation and his billing rate was $295 per hour (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 38).

105. As discussed in Section III.G.1.a, supra, the rates sought for Pryor Cashman attorneys and paralegals exceed those which are normally awarded by courts within this district for attorneys in employment litigations.

106. Because plaintiff has not provided the qualifications of the attorneys and staff at Pryor Cashman other than their job titles -- i.e., whether they were partners or associates -- I conclude that Pryor Cashman partners are only entitled to the hourly rate for experienced attorneys, as set forth in paragraph 90, supra, and that Pryor Cashman associates are entitled to the hourly rate for more inexperienced attorneys, as set forth in paragraph 91, supra.

107. Accordingly, I recommend that Zuckerberg, Raynor, Woldenberg and Dunworth’s hourly rates be reduced to $300 and that Pasternak and Stein’s hourly rates reduced to $175.

108. Further, for the same reasons as discussed in paragraphs 93, supra, I recommend that Mitchell be awarded a reduced hourly rate of $100.

*15 109. Finally, because plaintiff has offered no explanation as to the duties and responsibilities of an E-Discovery Specialist or a court clerk, I recommend that no fees be awarded for Antoniou, Dominguez and Hernandez’s time. Melgadejo v. S & D Fruits & Vegetables Inc., supra, 2015 WL 10353140 at *26 (recommending no award for an intern’s time where “plaintiffs’ counsel has failed to provide the identity or qualifications of this individual”).

2. Reasonable Number of Hours

110. The Honorable Loretta A. Preska, United States District Judge, has summarized the factors to be considered in assessing the reasonableness of the hours claimed in a fee application:

To assess the reasonableness of the time expended by an attorney, the court must look first to the time and work as they are documented by the attorney’s records. See Forschner Group, Inc. v. Arrow Trading Co., Inc., No. 92 Civ. 6953 (LAP), 1998 WL 879710, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 15, 1998). Next the court looks to “its own familiarity with the case and its experience generally .... Because attorneys’ fees are dependent on the unique facts of each case, the resolution of the issue is committed to the discretion of the district court.” AFP Imaging Corp. v. Phillips Medizin Sys., No. 92 Civ. 6211 (LMM), 1994 WL 698322, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 13, 1994) (quoting Clarke v. Frank, 960 F.2d 1146, 1153 (2d Cir. 1992)(quoting DiFilippo v. Morizio, 759 F.2d 231, 236 (2d Cir. 1985))).

* * *

Finally, billing judgment must be factored into the equation. Hensley, 461 U.S. at 434; DiFilippo, 759 F.2d at 235-36. If a court finds that the fee applicant’s claim is excessive, or that time spent was wasteful or duplicative, it may decrease or disallow certain hours or, where the application for fees is voluminous, order an across-the-board percentage reduction in compensable hours. In re “Agent Orange” Products Liab. Litig., 818 F.2d 226, 237 (2d Cir. 1987) (stating that “in cases in which substantial numbers of voluminous fee petitions are filed, the district court has the authority to make across-the-board percentage cuts in hours ‘as a practical means of trimming fat from a fee application’ ” (quoting Carey, 711 F.2d at 1146)); see also United States Football League v. National Football League, 887 F.2d 408, 415 (2d Cir. 1989) (approving a percentage reduction of total fee award to account for vagueness in documentation of certain time entries).

Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Co. v. Spitzer, 00 Civ. 7274 (LAP), 00 Civ. 7750 (LAP), 2002 WL 498631 at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 29, 2002) (Preska, D.J.); accord Hensley v. Eckerhart, supra, 461 U.S. at 434 (Courts “should exclude ... hours that were not reasonably expended,” such as where there is overstaffing or the hours are “excessive, redundant, or otherwise unnecessary.” (internal quotation marks omitted)); Gierlinger v. Gleason, 160 F.3d 858, 876 (2d Cir. 1998); Orchano v. Advanced Recovery, Inc., 107 F.3d 94, 98 (2d Cir. 1997). “The relevant issue ... is not whether hindsight vindicates an attorney’s time expenditures, but whether, at the time the work was performed, a reasonable attorney would have engaged in similar time expenditures.” Grant v. Martinez, 973 F.2d 96, 99 (2d Cir. 1992).

111. As noted above, plaintiff has produced contemporaneous time records from both Pryor Cashman and the Fensterstock firm. Specifically, plaintiff has submitted 67 pages of contemporaneous billing records from the Fensterstock firm and 53 pages of contemporaneous billing records from Pryor Cashman. In total, plaintiff seeks fees for 866.8 hours from the Fensterstock firm and 278.8 hours from Pryor Cashman, or 1,145.6 hours in total (Pl. PFFCL, ¶ 33-35; Walpert Aff., Ex. E). Based upon my review of these records, as well as my familiarity with the litigation, I conclude that the number of hours for which compensation is sought is excessive and warrants reduction.

*16 112. As an initial matter, both the Fensterstock firm and Pryor Cashman’s records reveal several instances of improper block billing. Block billing “impedes a court’s ability to assess whether the time expended on any given task was reasonable.” Beastie Boys v. Monster Energy Co., 112 F. Supp. 3d 31, 53 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (Engelmeyer, D.J.) (noting that “block billing is most problematic where large amounts of time (e.g., five hours or more) are block billed; in such circumstances, the limited transparency afforded by block billing meaningfully clouds a reviewer’s ability to determine the projects on which significant legal hours were spent.”); accord Charles v. City of New York, 13 Civ. 3547 (PAE), 2014 WL 4384155 at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 4, 2014) (Engelmeyer, D.J.) (reducing a partner’s fee award for block-billed entries, including one 5.2 hour entry that stated, “Prep to conduct defendants depositions-review discovery materials including CCRB files, defendants statements, arrest reports, draft deposition outline, formulate strategy, draft questions for Brito”); Williams v. New York City Hous. Auth., 975 F. Supp. 317, 327 (S.D.N.Y. 1997) (Ward, D.J.) (“Fee applicants should not ‘lump’ several services or tasks into one time sheet entry because it is then difficult, if not impossible, for a court to determine the reasonableness of the time spent on each of the individual services or tasks provided ....”), quoting In re Poseidon Pools of America, Inc., 180 B.R. 718, 731 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 1995) (citations omitted). For example, the Fensterstock firm’s billing records for just the month of March 2014 include two instances where Philips block-billed for more than six hours and spent that time working on at least seven different tasks and two more instances where Philips block-billed for more than eight hours and spent that time working on at least seven different tasks (Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 2, at 3-4[15]).[16]

113. Pryor Cashman’s records also include several instances of improper block billing. For example, Pasternak’s April 14, 2013 time entry indicates she spent 3.6 hours on four separate tasks, Woldenberg’s August 15, 2013 time entry indicates Woldenberg spent 4 hours on three separate tasks, Pasternak’s January 13, 2014 time entry indicates she spent 8.3 hours on eight separate tasks and Pasternak’s January 14, 2014 time entry indicates she spent 4.1 hours on seven separate tasks (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 7, 18, 29, 35).[17]

114. Additionally, many of the non-block-billed entries in Pryor Cashman’s records are too vague to permit an analysis as to whether the number of hours spent is reasonable. In re W. End Fin. Advisors, LLC, No. 11-11152 SMB, 2012 WL 2590613 at *5 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. July 3, 2012) (Bernstein, B.J.) (“[V]ague and ambiguous descriptions of work done prevent the court from assessing the reasonableness of the work, and should be eliminated or reduced.”), citing, inter alia, Cosgrove v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 81 Civ. 3482 (AGS), 1996 WL 99390 at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 7, 1996) (Schwartz, D.J.) (“[M]any of the descriptions of the work performed are vague, including entries such as ‘review of file,’ ‘review of documents’ and ‘review of [adversary’s] letter.’ There can be no meaningful review of time records where the entries are too vague to determine whether the hours were reasonably expended.”). For example, several of the entries include descriptions such as “Draft letter to Jaffrey,” “Call with client,” “E-mail to Jaffrey,” “Call with E. Walpert,” “Call with Woldenberg and Walperts,” “Write client,” “Emails with client,” “Call with opposing counsel,” “Write opposing counsel,” “Email client” and “Email with opposition” without including any explanation or description of the issues being discussed in those communications (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 13, 16, 18, 25, 30, 33, 46).

*17 115. Further, the number of hours billed should be reduced because plaintiff’s decision to change counsel in the midst of litigation led to redundancies; the attorneys at the Fensterstock firm necessarily spent time learning facts that were already known to the Pryor Cashman attorneys. See Hensley v. Eckerhart, supra, 461 U.S. at 434 (Courts “should exclude ... hours that were not reasonably expended,” such as where hours are “redundant” (internal quotation marks omitted)). While plaintiff undoubtedly had the unfettered right to change counsel, his decision to do so required the Fensterstock firm to spend over 75 hours in the first two weeks after it was retained by plaintiff conferring with Pryor Cashman and organizing and reviewing the client file (Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 2, at 2-5) -- time that would not have been necessary but for plaintiff’s decision to switch counsel in the middle of litigation. During that same time period, the Fensterstock firm also billed plaintiff for 26.3 hours spent by O’Shea on “[c]reat[ing] an informational chart about important documents” (Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 2, at 4-5). Pryor Cashman’s records also include 4.8 hours of unnecessary billable time that was spent on transferring plaintiff’s file to the Fensterstock firm and communicating with the Fensterstock firm (Walpert Aff., Ex. E, at 47).

116. Both Pryor Cashman and the Fensterstock firm also appear to have overstaffed this matter.

Where a plaintiff is represented by multiple attorneys ... a court reviewing a fee application should be particularly attentive to the risk of inefficiency and avoid making the defendant subsidize it. Separate fee awards for lawyers collaborating on the same matter are “palatable only [to the extent that] counsel were committed to ensuring that the total number of hours expended over the course of the litigation was not unreasonably increased thereby.”

Cruceta v. City of New York, No. 10-CV-5059 FB JO, 2012 WL 2885113 at *6 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 7, 2012) (Report & Recommendation), adopted, 2012 WL 2884985 (E.D.N.Y. July 13, 2012), quoting Simmonds v. New York City Dep’t of Corrections, 06 Civ. 5298 (NRB), 2008 WL 4303474 at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Sept.16, 2008) (Buchwald, D.J.). In this matter, Pryor Cashman used six attorneys, including four partners, as well as a paralegal, two E-Discovery specialists and a court clerk. The Fensterstock firm also overstaffed, using seven attorneys, including three partners, and four paralegals.

117. Finally, and most importantly, the 1,145.6 hours worked by the two firms in litigating this action is clearly excessive for the amount of work required by this case. Although plaintiff’s counsel drafted a complaint and amended complaint, engaged in some discovery, attended several conferences concerning defendants’ failure to retain permanent counsel and were required to submit detailed submissions with respect to the default and this inquest, which included conducting a two-day hearing on the default motion, this case did not conclude in a full trial and did not involve any dispositive motions other than the default motion. Further, there is no indication that plaintiff took any depositions and the record indicates that plaintiff’s counsel only had to review approximately 203 pages of defendants’ documents in discovery. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 116.[18]

118. Comparable cases involving employment disputes in which the defendants originally made an appearance before defaulting demonstrate that the number of hours billed here is severely inflated. See Bazignan v. Team Castle Hill Corp., supra, 2015 WL 1000034 at *1, *5 (finding 118.18 hours reasonable in an employment litigation in which the defendants originally defaulted, later sought to vacate the entry of default and filed an answer and then failed to participate further in discovery after filing their answer, resulting in a reinstatement of their default and an inquest to determine plaintiff’s damages, in which only plaintiff participated); Easterly v. Tri-Star Transp. Corp., 11 Civ. 6365 (VB), 2015 WL 337565 at *2, *11 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 23, 2015) (Briccetti, D.J.) (finding 151.4 hours reasonable where “[f]or nearly two years, Defendants appeared through counsel, whose active participation in the case included discovery and a settlement conference” before subsequently defaulting, requiring plaintiff’s counsel to spend time “on the complaint, the exchange of discovery, the default motion, and this damages inquest, [as well as] ... discovery disputes, settlement discussions, depositions, a summary judgment motion, the bankruptcy of individual defendants, and withdrawal of opposing counsel”); Guallpa v. N.Y. Pro Signs Inc., supra, 2014 WL 2200393 at *1, *12(recommending a 15 percent reduction to a request for 523 hours of legal fees in a case in which the defendant defaulted after failing to comply with two court orders and failed to respond to an order to show cause); see alsoNi v. Bat-Yam Food Servs. Inc., 13 Civ. 07274 (ALC)(JCF), 2016 WL 369681 at *8-*9 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 27, 2016) (Carter, D.J.) (finding 176.3 hours reasonable in an employment litigation that (1) lasted for more than two years and involved eight plaintiffs, (2) included six months of discovery where defendants “were delinquent in their production on multiple occasions, resulting in Plaintiffs filing motions to compel”, (3) included the litigation by the parties of a motion by the defendants to file an amended answer, (4) required the plaintiffs’ counsel to translate documents produced by defendants from Chinese and into English and translate for many of their clients and (5) involved a summary judgment motion on which the plaintiffs prevailed in substantial part). While the foregoing cases indicate that the number of hours billed here far exceeds what is reasonable, I appreciate that the present case involved certain issues that may have reasonably required more time. For instance, plaintiff’s counsel prepared for at least one deposition that was subsequently adjourned through no fault of plaintiff and were faced with the unusual circumstance of participating in a two-day hearing on their default motion. Additionally, defendants’ refusal to retain counsel required plaintiff’s counsel to attend in-court conferences at a more frequent rate than would be typical for this type of litigation. Most importantly, the above-cited cases involved wage and hour claims concerning unpaid overtime and/or minimum wage with relatively modest recoveries for the plaintiffs, ranging from nearly $14,000 to nearly $300,000. In this case, on the other hand, plaintiff’s claims relate to an employment contract and have resulted in damages exceeding $5,000,000. Nevertheless, while these unique circumstances distinguish this case from a more typical wage-and-hour employment litigation, they do not justify the over 1,000 hours billed in this matter. Therefore, I conclude that plaintiff’s fee application requires reduction, and, because plaintiff’s records are lengthy and the issues described in the preceding paragraphs are merely representative of issues found throughout plaintiff’s records, I recommend that the court apply a 35 percent across-the-board cut to plaintiff’s requested hours.

*18 119. Accordingly, I recommend that plaintiff be awarded $32,318.00 for the work done by Pryor Cashman and 160,655.63 for the work done by the Fensterstock firm, or a total of $192,973.63 in attorneys fees.[19]

3. Costs

120. Plaintiff also seeks $8,514.80 in costs incurred by Pryor Cashman and $12,921.71 in costs incurred by the Fensterstock firm.

121. As noted above, fee awards “normally include those reasonable out-of-pocket expenses incurred by the attorney and which are normally charged fee-paying clients.” Reichman v. Bonsignore, Brignati & Mazzotta P.C., supra, 818 F.2d at 283 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted). Accordingly, courts, in their discretion, have awarded reasonable costs for various expenses, including computer research, attorney transportation and meals, mailing and copying fees and service and filing fees. See, e.g., Kim v. Kum Gang, Inc., supra, 2015 WL 3536593 at *7; Rosendo v. Everbrighten Inc., 13 Civ. 7256 (JGK)(FM), 2015 WL 1600057 at *9 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 7, 2015) (Maas, M.J.) (Report & Recommendation), adopted, 2015 WL 4557147 (S.D.N.Y. July 28, 2015) (Koeltl, D.J.); Reiseck v. Universal Commc’ns of Miami, Inc., supra, 2014 WL 5374684 at *8.

122. I have reviewed the costs sought by both firms and conclude that they are reasonable. Accordingly, I recommend plaintiff be awarded $8,514.80 in costs incurred by Pryor Cashman and $12,921.71 in costs incurred by the Febsterstock firm, or a total of $21,436.51 in costs.[20]

IV. Conclusion

For all of the foregoing reasons, I respectfully recommend that judgment be entered for plaintiff and against the defendants in the amount of $5,972,474.72, comprised of $2,612,500 on plaintiff’s contract claim, $2,054,326.92 on plaintiff’s NYLL claim, $1,091,237.66 in pre-judgment interest through August 31, 2016, $192,973.63 in attorneys’ fees and $21,436.51 in costs.

Further, because the assessment of compensatory damages with respect to plaintiff’s quasi-contract claims and conversion claim turns almost exclusively on the testimony of two opposed, interested parties -- plaintiff and Jaffrey -- with almost no documentary evidence supporting either’s position, I do not recommend any compensatory damages with respect to those claims at this point; rather, I believe that a viva voce hearing is necessary to assess damages with respect to those claims. However, because there appears to be substantial collection issues in this action, there may be no incremental benefit to plaintiff in continuing to pursue damages on these claims. Accordingly, within fourteen (14) days of this Report and Recommendation, plaintiff’s counsel is to advise as to whether plaintiff wishes to proceed with a viva voce hearing with respect to the quasi-contract and conversion claims.

V. Objections

*19 Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1)(C) and Rule 72(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the parties shall have fourteen (14) days from receipt of this Report to file written objections. See also Fed.R.Civ.P. 6(a). Such objections (and responses thereto) shall be filed with the Clerk of the Court, with courtesy copies delivered to the Chambers of the Honorable Paul G. Gardephe, United States District Judge, 40 Centre Street, Room 2204, and to the Chambers of the undersigned, 500 Pearl Street, Room 750, New York, New York 10007. Any requests for an extension of time for filing objections must be directed to Judge Gardpehe. FAILURE TO OBJECT WITHIN FOURTEEN (14) DAYS WILL RESULT IN A WAIVER OF OBJECTIONS AND WILL PRECLUDE APPELLATE REVIEW. Thomas v. Arn, 474 U.S. 140, 155 (1985); United States v. Male Juvenile, 121 F.3d 34, 38 (2d Cir. 1997); IUE AFL-CIO Pension Fund v. Herrmann, 9 F.3d 1049, 1054 (2d Cir. 1993); Frank v. Johnson, 968 F.2d 298, 300 (2d Cir. 1992); Wesolek v. Canadair Ltd., 838 F.2d 55, 57-59 (2d Cir. 1988); McCarthy v. Manson, 714 F.2d 234, 237-38 (2d Cir. 1983) (per curiam).

APPENDIX

Footnotes

Plaintiff’s amended complaint also names US Defense Fund Management LLC (“USDFM”) as a defendant (Am. Compl., ¶ 1). However, following the hearing on plaintiff’s default motion, plaintiff moved pursuant to Rule 21 to dismiss USDFM from the action, which motion was granted by the Honorable Paul G. Gardephe, United States District Judge, on August 28, 2015. Walpert v. Jaffrey, 127 F. Supp. 3d 105, 120-21 (S.D.N.Y. 2015)(Gardephe, D.J.).

Although I granted defendants an extension only until January 23, 2016, that date was a Saturday and January 25, 2016 was the next business day on the calendar. Accordingly, defendants’ submissions were timely. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 6(a)(1)(C).

As a result of defendants’ default, all of the allegations of the amended complaint, except as to the amount of damages, must be taken as true. Bambu Sales, Inc. v. Ozak Trading Inc., 58 F.3d 849, 854 (2d Cir. 1995); Greyhound Exhibitgroup, Inc. v. E.L.U.L.Realty Corp., 973 F.2d 155, 158-59 (2d Cir. 1992).

In their proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law, defendants offer no evidence of their own to rebut plaintiff’s contentions regarding the amount he was paid. Instead, defendants complain that plaintiff’s initial complaint sought a lesser amount of contractual damages than his amended complaint and included different factual allegations than the amended complaint (Defs. PFFCL, ¶¶ 1-2). Defendants have also included an affidavit from Jaffrey that denies the validity of the Agreement (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶¶ 16-17). However, I do not consider Jaffrey’s challenges to the validity of the contract because liability on the contract claim was established in Judge Gardephe’s August 28, 2015 Opinion. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 130-34.

Because Exhibit B to Walpert’s affidavit lacks consistent internal pagination, in subsequent references to this document, I refer to the page numbers assigned by the Court’s ECF system.

For example, the journal entry for October 1, 2010 states “Delta - ALL DAY,” providing good support for plaintiff’s statement in his affidavit that he had an “[a]ll day meeting at Delta Search” on that date (Walpert Aff., ¶ 22 at October 1, 2010 entry & Ex. B-1, at 15). However, the journal entry for February 21, 2011 simply states “Kamal,” providing little to no support for plaintiff’s statement in his affidavit that he did work “regarding Delta Search” on that date (Walpert Aff., ¶ 22 at February 21, 2011 entry & Ex. B-2, at 10).

Jaffrey disputes this, stating in his affidavit that he paid Byrne Poh for the work done for Delta Search and that the $50,000 check he gave plaintiff was meant to pay for Byrne Poh’s fees; however, Jaffrey does not explain why this check was written to plaintiff and not Byrne Poh (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 15).

I calculated the weekly salary by taking plaintiff’s $900,000 yearly salary under the Agreement and dividing it by 52 weeks ($900,000 ÷ 52 = $17,307.69).

Defendants also argue that the furniture removed from plaintiff’s office was “placed in storage at plaintiff’s request and as a favor to plaintiff by Mr. Jaffrey” (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 17). Defendants’ support for this argument is Jaffrey’s affidavit, in which he states that “when Wingate/USDFM vacated the [Wingate office space], Walpert requested that, as a personal favor, I remove some of his property and store the property with my own stuff for a few weeks until he could arrange to move his property” (Defs. PFCCL, Ex. C, ¶ 20). Jaffrey further states that a limousine driver, “Raffy,” stole the storage container in which defendants’ property was contained (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 21). Finally, Jaffrey states that the boxes of books and other items were delivered to plaintiff’s firm, Byrne Poh, on March 1, 2013 after plaintiff requested Jaffrey send them to that location (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. C, ¶ 23). In support of this allegation, Jaffrey includes a purported text message sent to him by “Ali Ansari,” the person who apparently delivered these boxes to the delivery service, which states, “Rashid Jon sent via fed ex tracking number 794854323585 on 2/27/2013 to Att Gary walpert delivered 3/1/2013 at 10.57am signed by R VO total weight 90LBS thanks I will have the hard copy for you” (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. A). I do not, however, consider defendants’ challenges as to liability on the conversion claim because liability was established in Judge Gardephe’s August 28, 2015 Memorandum Opinion and Order. Walpert v. Jaffrey, supra, 127 F. Supp. 3d at 135-36.

In fact, other than Joshua Zuckerberg and Rachel J. Pasternak, who made appearances on the docket in this action, plaintiff has not even provided these individuals’ full names; the billing records submitted only provide a surname and initials for first and middle names.

Because Pryor Cashman’s contemporaneous billing records lack consistent internal pagination, I refer to the page numbers provided by the Court’s ECF system.

Because the Fensterstock firm’s billing records lack consistent internal pagination, I refer to the page numbers assigned by the Court’s ECF system.

These are not the only examples of block billing in the Fensterstock firm’s records that are too vague and unclear to permit an analysis of the reasonableness of the hours spent; rather, they merely serve as an example of the type of block billing found throughout the records. Further, as defendants note in their submissions, the same March 2014 records discussed above also reveal instances where one attorney’s time entry reflects that a meeting occurred with another attorney but the other attorney’s time entry does not reflect that same meeting (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 8; Fensterstock Aff., Ex. 2, at 3).

As was the case with the Fensterstock firm’s records, these are not the only examples of improper and vague block billing in Pryor Cashman’s records.

Additionally, plaintiff does not indicate how many documents it reviewed or produced in connection with defendants’ discovery requests. Further, although plaintiff did make an application to amend his complaint and a few applications challenging the completeness of defendants’ document production and seeking conferences to resolve such disputes, those applications did not include lengthy formal briefing (See Docket Items 17, 31, 42, 45).

I reach this number by multiplying the total number of hours worked by each attorney or paralegal, excluding Pryor Cashman’s E-Discovery Specialists and court clerk for the reasons discussed in paragraph 109, supra, by 0.65 and then multiplying the product of that equation by the hourly rates set forth above. These calculations are set forth in the Appendix attached hereto.

Defendants argue that the Fensterstock firm’s costs for data hosting are both unnecessary and excessive (Defs. PFFCL, ¶ 9). In support of this argument, defendants cite to an unauthenticated exhibit that includes e-mails between plaintiff’s counsel and a person who appears to be a data-hosting vendor in which the vendor quotes a monthly price of $20-$30 per gigabyte and states that 2000 documents would usually require half of a gigabyte or less of data hosting capacity (Defs. PFFCL, Ex. B). Defendants do not state how many documents they believe plaintiff was hosting or what the basis for any such belief would be. In sum, I do not find defendants’ argument persuasive and conclude that plaintiff is entitled to the costs incurred for data hosting.