Scrap King LLC v. Stericycle, Inc.

Scrap King LLC v. Stericycle, Inc.

2023 WL 3751993 (M.D. Fla. 2023)

May 8, 2023

Porcelli, Anthony e., United States Magistrate Judge

Summary

The court found that the defendant had failed to meet its discovery obligations by failing to timely produce emails and manifests, and awarded monetary sanctions to the plaintiff in the form of attorneys' fees and costs associated with matters related to the plaintiff's pursuit of the emails and manifests. The court reduced the plaintiff's requested fees and costs by thirty percent due to the presence of irrelevant, duplicative, excessive, and “block-billed” entries.

Additional Decisions

SCRAP KING LLC, Plaintiff,

STERICYCLE, INC., Defendant

STERICYCLE, INC., Defendant

Case No. 8:18-cv-733-MSS-AEP

United States District Court, M.D. Florida

Filed May 08, 2023

Counsel

Stuart Jay Levine, Jamie Alexandra Kilpatrick, Walters Levine Klingensmith & Thomison, PA, Tampa, FL, for Plaintiff.Richard George Salazar, Lauren Virginia Humphries, Joshua Samuel Michael Smith, Ashley Bruce Trehan, Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney, PC, Tampa, FL, for Defendant.

Porcelli, Anthony e., United States Magistrate Judge

ORDER

*1 Before the Court is the outstanding issue of the amount of attorneys’ fees to which Plaintiff, Scrap King LLC (“Plaintiff”), is entitled. The Court previously decided the issue of entitlement and awarded Plaintiff attorneys’ fees as a monetary sanction pursuant to Rules 26(g) and 37(b) (see Doc. 147; Doc. 158, at 104; Doc. 282, at 9). In support of this decision, the undersigned has considered Plaintiff's Interim Motion for Payment of Awarded Attorneys’ Fees and Costs as Sanctions (Doc. 192), Notice of Filing Additional Attorney's Fees and Costs for the Period May 31, 2020 to October 31, 2020 (Doc. 249), and Notice of Filing Updated Attorneys’ Fees and Costs (Doc. 276). The undersigned also considered Defendant's Response in Opposition to Plaintiff's motion for fees (Doc. 206) and Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's Notice of Filing Updated Attorneys’ Fees and Costs (Doc. 279). On March 14, 2023, the Court held a hearing on the matter at which attorneys for Plaintiff and Defendant appeared and presented oral argument (Doc. 297).

I. Procedural and Factual History

The procedural history of this matter is fully detailed in the Court's Order Denying Sanctions (Doc. 282) and incorporated herein. The relevant procedural and factual history is briefly summarized as follows.

On April 8, 2019, Plaintiff filed a Motion to Compel Production of Documents, seeking the production of emails and manifests that Plaintiff alleged existed but had not been produced (Doc. 41). In the Motion to Compel Production of Documents, Plaintiff also made its initial request for sanctions due to spoliation (Doc. 41, at 12). The Court conducted a hearing on Plaintiff's Motion to Compel Production of Documents (Doc. 41) and afterward the undersigned resolved the motion in an Order which allowed Plaintiff to obtain discovery limited to Defendant's email and records (e.g., manifests) retention policies, directed Defendant to produce any responsive discovery as to the remaining discovery requested, and denied without prejudice Plaintiff's request for sanctions for spoliation of evidence (Doc. 54).

Plaintiff deposed several former and current employees of Defendant whose testimony seemed to contradict the stated email retention policy of Defendant (Doc. 117, at 5-7). Plaintiff then noticed the deposition of Amanda Metts as a Rule 30(b)(6) witness to speak to Defendant's retention policies (Doc. 117, at 7). Defendant filed a protective order (Doc. 70). After a hearing, the Court granted Defendant's motion as to Ms. Metts but found an additional Rule 30(b)(6) deposition was warranted, particularly to answer questions regarding Defendant's retention policy (Doc. 92, at 36). Thus, in October 2019, Plaintiff deposed Candace Lawber, a corporate paralegal who worked under Ms. Metts, and she testified that a number of employees who were relevant to this case were presently under a litigation hold or otherwise exempt from the deletion policy (Doc. 117, at 9-10).

Plaintiff filed an Expedited Motion for Sanctions Pursuant to Rule 37(b) seeking sanctions for Defendant's failure to preserve and produce relevant email communications (Doc. 117). Additionally, Plaintiff filed a Motion for Sanctions Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e)(2) seeking sanctions for Defendant's failure to preserve and produce relevant manifests (Doc. 131). The Court conducted a telephonic status hearing on Plaintiff's sanction motions on January 3, 2020 (see Doc. 141). It was developed during the status hearing that there were seven custodians whose email accounts Defendant preserved based upon litigation holds not related to this case and that the requested manifests were in the possession of a non-party vendor who maintained the manifests for Defendant (Doc. 141, at 7, 6-11).

*2 On January 16, 2020, the parties appeared before the undersigned to continue their arguments on Plaintiff's sanction motions (Docs. 117 & 131) and to address the undersigned's outstanding questions from the January 3, 2020 telephonic status hearing (see Doc. 158). Ultimately, the Court awarded monetary sanctions to Plaintiff pursuant to Rules 26(g) and 37(b) in the form of fees and costs associated with matters related to Plaintiff's pursuit of the manifests after the Court ordered that the manifests be produced as well as Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the emails not produced (see Doc. 158, at 107; Doc. 282, at 9). Upon the conclusion of the January 16, 2020 hearing, the undersigned made the following findings:

I find it appropriate to award sanctions to Scrap King in the form of monetary sanctions.

Given the time that has been expended in tracking down these manifests, I'm going to award sanctions beginning upon the time expended on the original motion to compel filed on April 8th, the attendance of any hearings related to these discovery disputes regarding the manifests, as well as any other subsequent pleadings.

...

[I find] an inadequacy in the production of the discovery, whether it be based upon a position that the manifests were not in the possession, custody or control, one that I find no basis for that position, or alternatively, a failure to adequately search e-mails. That has cost the plaintiff time and resources, which I find that they need to be compensated for ....

(Doc. 158, at 104-107). The undersigned took under advisement the amount of fees to be awarded and reserved ruling on the issue of whether fees associated with depositions would be covered as well (Doc. 158, at 104, 108-109). The undersigned memorialized these findings following the hearing, reiterating that Defendant must pay Plaintiff's fees and costs related to “Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the discovery pertaining to the requested e-mails and manifests” and encouraging the parties to come to an agreement as to the amount of fees (Doc. 147, at 2). The parties did not reach an agreement on the amount of fees.

Numerous disputes followed regarding the nature of the independent examination and the privilege assertions on various emails located by the expert (see Docs. 157, 167, 178, 182, 188, 195, 203, 215, 223). Upon the conclusion of the expert's independent examination, an additional 311 non-privileged, responsive emails were produced (Doc. 226, at 10). Given the production of the additional 311 emails, Plaintiff filed a motion (Doc. 226) requesting that Defendant be sanctioned pursuant to Rule 37(e) and the Court's inherent power. The undersigned denied Plaintiff's request for an adverse inference instruction due to insufficient evidence establishing that Defendant acted with bad faith or intent to deprive Plaintiff of relevant ESI (Doc. 282, at 28). The undersigned found:

Without question, Defendant woefully failed to meet its discovery obligations by failing to timely produce the manifests and email communications. Although such bad conduct during the course of discovery is sanctionable, the Court is unpersuaded to find that such conduct alone should equate a bad faith or intent to deprive finding. Rather, this Court has already ordered Defendant's conduct sanctionable under Rules 26(g) and 37(b) (see Doc. 158) and will award Plaintiff a monetary award as an appropriate sanction for such conduct.

(Doc. 282, at 26-27). Thus, before the Court is the outstanding issue of the amount of attorney's fees to which Scrap King is entitled.

In the time between the Court's award of fees in January 2020 and the Court's denial of Plaintiff's motion requesting an adverse inference instruction, Plaintiff has filed various billing records. Initially, Plaintiff filed an Interim Motion for Payment of Awarded Attorneys’ Fees and Costs as Sanctions (Doc. 192). Plaintiff attached billing records spanning from December 2018 to May 2020 (Docs. 192-2; Doc. 192-3). Defendant filed its response in opposition to Plaintiff's motion for fees (Doc. 206). Plaintiff then supplemented its request by filing billing records from May 2020 through October 2020 (Doc. 249) and November 2020 through May 2022 (Doc. 276). Defendant filed its Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's Notice of Filing Updated Attorneys’ Fees and Costs (Doc. 279). On March 14, 2023, the undersigned held a hearing regarding the amount of attorney's fees at which attorneys for Plaintiff and Defendant appeared and presented oral argument (Doc. 297).

II. Discussion

*3 Defendant does not principally dispute the undersigned's finding that Plaintiff is entitled to fees relating to the emails and manifests (Doc. 279, at 3). Defendant also waived objections to Plaintiff's attorneys’ stated hourly rates during the hearing on March 14, 2023 (Doc. 297). Instead, Defendant's primary objection to the fee request concerns the amount of hours Plaintiff asserts should be included and the quality of the records supporting Plaintiff's requests. Defendant contends that Plaintiff's fee requests are overinclusive and unsupportable, taking a strict view of what constitutes Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the requested emails and manifests (Doc. 206, at 3; Doc. 279, at 3). Defendant also argues the billing records “contain rampant block billing” and the entries are inflated, making it impossible to ascertain which hours were spent on the relevant tasks (Doc. 206, at 4).

The fees at issue were awarded as sanctions under Rules 26(g) and 37(b) (see Doc. 158). Rule 26(g) provides that “[e]very disclosure under Rule 26(a)(1) or (a)(3) and every discovery request, response, or objection must be signed by at least one attorney of record” and that “[b]y signing, an attorney or party certifies that to the best of the person's knowledge, information, and belief formed after a reasonable inquiry” the disclosure “is complete and correct as of the time it is made.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(g)(1). If a party signs a disclosure in violation of this rule, “the court, on motion or on its own, must impose an appropriate sanction” which may, as here, “include an order to pay the reasonable expenses, including attorney's fees, caused by the violation.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(g)(3). Rule 37(b) provides for sanctions relating to failure to comply with a court order and, as applicable here, “[i]f a party or a party's officer, director, or managing agent ... fails to obey an order to provide or permit discovery” among other things, “the court must order the disobedient party, the attorney advising that party, or both to pay the reasonable expenses, including attorney's fees, caused by the failure, unless the failure was substantially justified or other circumstances make an award of expenses unjust.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(b)(2)(A), (C).

As an initial matter, it is worth mentioning that Defendant somewhat disputes entitlement, at least as to work performed for Plaintiff's spoliation motion. Defendant contends that because the undersigned found that there was no spoliation, all fees associated with efforts to prove spoliation must be excluded (Doc. 206, at 4, 7).[1] The undersigned disagrees. Defendant's discovery misconduct caused Plaintiff to file its spoliation motions and is therefore properly compensated under Rule 37(b). First, Rule 37(b) fee awards, unlike sanctions imposed pursuant to the court's inherent powers or sanctions imposed under Rule 37(e)(2), do not require a finding of bad faith or intent. See DeVaney v. Continental Am. Ins. Co., 989 F.2d 1154, 1162 (11th Cir.1993) (“We are satisfied that subsection 37(b)(2) ... demands no demonstration of bad faith.”). Thus, the Court's rejection of spoliation-based sanctions on the grounds of a lack of bad faith or intent is inapposite to the entitlement to Rule 37(b) fees. Second, but for Defendant's discovery misconduct, Plaintiff would not have been required to pursue spoliation sanctions. Rule 37(b)(2) requires a causal connection between the litigant's misconduct and the legal fees incurred by the opposing party. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Haeger, 137 S. Ct. 1178, 1186 n.5 (2017). That kind of causal connection is “appropriately framed as a but-for test”: the complaining party may recover only the portion of fees that he would not have paid but for the misconduct. Id. at 1187 (citation omitted); see Fox v. Vice, 563 U.S. 826, 836, 131 S.Ct. 2205, 180 L.Ed.2d 45 (2011); Paroline v. United States, 572 U.S. 434, 449-50, 134 S.Ct. 1710, 1722, 188 L.Ed.2d 714 (2014) (“The traditional way to prove that one event was a factual cause of another is to show that the latter would not have occurred ‘but for’ the former”). Here, the undersigned found “[w]ithout question, Defendant woefully failed to meet its discovery obligations by failing to timely produce the manifests and email communications” but that despite that conduct being sanctionable, was ultimately “unpersuaded to find that such conduct alone should equate a bad faith or intent to deprive finding” (Doc. 282, at 26-27). While Defendant is correct that the Court ultimately rejected Plaintiff's spoliation arguments, Plaintiff's work to prove spoliation should not go uncompensated simply because it was unsuccessful. Defendant's misconduct, while not intentional or taken in bad faith, was nonetheless the but-for cause of Plaintiff's substantially justified spoliation pursuits. Therefore, Plaintiff's spoliation pursuits are properly included in its Rule 37(b) fees.

*4 In determining reasonable attorney's fees, the court applies the federal lodestar approach, by multiplying the number of hours reasonably expended on the litigation by the reasonable hourly rate for the services provided by counsel for the prevailing party. Loranger v. Stierheim, 10 F.3d 776, 781 (11th Cir. 1994) (per curiam). “[T]he fee applicant bears the burden of establishing entitlement to an award and documenting the appropriate hours expended and hourly rates.” Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 437 (1983). There is a “strong presumption that the lodestar figure ... represents a ‘reasonable’ fee.” Smith v. Atlanta Postal Credit Union, 350 F. App'x 347, 349 (11th Cir. 2009) (citing Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens’ Council for Clean Air, 478 U.S. 546, 565, 106 S.Ct. 3088, 92 L.Ed.2d 439 (1986)). But “[u]ltimately, the computation of a fee award is necessarily an exercise of judgment, because ‘[t]here is no precise rule or formula for making these determinations.’ ” Villano v. City of Boynton Beach, 254 F.3d 1302, 1305 (11th Cir. 2001) (quoting Hensley, 461 U.S. at 436). Once the court has determined the lodestar, it may adjust the amount upward or downward based upon a number of factors. Norman v. Hous. Auth. of the City of Montgomery, 836 F. 2d 1292, 1302 (11th Cir. 1988). Additionally, the court is “ ‘an expert on the question [of attorneys’ fees] and may consider its own knowledge and experience concerning reasonable and proper fees and may form an independent judgment either with or without the aid of witnesses as to value.’ ” Norman, 836 F. 2d at 1303 (quoting Campbell v. Green, 112 F.2d 143, 144 (5th Cir. 1940)).

Trial courts undertaking the task of quantifying attorney's fees caused by sanctionable conduct “need not, and indeed should not, become green-eyeshade accountants.” Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 581 U.S. at 110 (citation and internal quotation marks omitted); see Loranger, 10 F.3d at 783 (“When faced with a massive fee application ... an hour-by-hour review is both impractical and a waste of judicial resources.”). As noted by the Supreme Court, “ ‘[t]he essential goal’ in shifting fees is ‘to do rough justice, not to achieve auditing perfection’ ” and accordingly, “a district court ‘may take into account [its] overall sense of a suit, and may use estimates in calculating and allocating an attorney's time.’ ” Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 581 U.S. at 110 (citing Fox, 563 U.S. at 836). The court may decide, for example, that all, or a set percentage, of a particular category of expenses were incurred solely because of a litigant's sanctionable conduct. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 581 U.S. at 110; see Loranger, 10 F.3d at 783 (noting that district courts may engage in “across-the-board percentage cuts either in the number of hours claimed or in the final lodestar figure” so long as the courts “concisely but clearly articulate their reasons for selecting specific percentage reductions”). These judgments, in light of the trial court's “superior understanding of the litigation,” are entitled to substantial deference on appeal. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 581 U.S. at 110 (citing Hensley, 461 U.S. at 437). Thus, the Eleventh Circuit reviews the imposition of sanctions under Rules 26 and 37, including awards of attorney's fees, for an abuse of discretion. Serra Chevrolet, Inc. v. Gen. Motors Corp., 446 F.3d 1137, 1146-47 (11th Cir. 2006); Bivins v. Wrap It Up, Inc., 548 F.3d 1348, 1351 (11th Cir. 2008); Malautea v. Suzuki Motor Co., 987 F.2d 1536, 1545 (11th Cir.1993) (court reviews sanctions under Rule 26(g) for abuse of discretion)

In support of its fee requests, Plaintiff has filed various billing records including an Interim Motion for Payment of Awarded Attorneys’ Fees and Costs as Sanctions (Doc. 192), and two supplemental filings of billing records from May 2020 through October 2020 (Doc. 249) and November 2020 through May 2022 (Doc. 276). Plaintiff's fee requests are summarized in this chart:

Thus, Plaintiff requests a total of $378,363.82 in fees for work performed and costs incurred from December 2018 to May 2022.

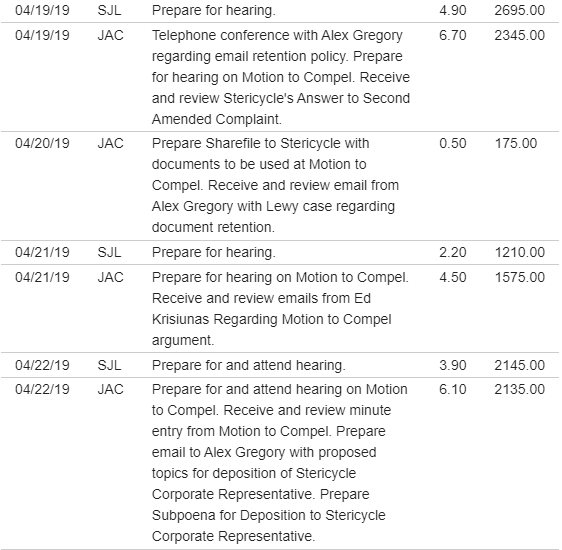

*5 After considering the records Plaintiff includes in support, the undersigned agrees with Defendant. Plaintiff's billing records are rife with irrelevant, duplicative, excessive, and “block-billed” entries. For example, the entries appear excessive and duplicative for work done in preparation for the April 22, 2019 hearing on Plaintiff's first motion to compel. The entries are the following:

(Doc. 192-2, at 3-4). That is, it appears Plaintiff's counsel spent a total of 28.8 hours and incurred fees of $12,280 preparing for the hearing on the motion to compel which lasted one hour and four minutes (Doc. 51). The motion to compel itself consisted of a two-page memorandum of law and a ten-page factual summary of the case and the requests for production at issue (Doc. 41). While, naturally, legal work is time consuming, the undersigned, based on its familiarity with the case and the issues brought to bear at the hearing finds 28.8 hours of work costing $12,280 excessive. These April 2019 records also show Plaintiff's propensity for block billing, which is otherwise common throughout the records. For one example of many, on August 2, 2019, “JAC” billed 5.4 hours for the following work:

Continue deposition digest of Robert Brown. Telephone conference with Alex Gregory regarding Second Request for Production and course of action. Meet with Stuart J. Levine regarding course of action. Prepare email to Jennifer Mcloone regarding dates for deposition of Stryker Solutions Corporate Representative. Telephone conference with Ashley Trehan regarding depositions, expert reports, mediation rescheduling. Research regarding Non-Party Objection to Subpoena. Revise Good Faith letter to Stryker. Prepare deposition digest of Selin Hoboy.

(Doc. 192-2, at 8). The undersigned is unable to discern which portion of the 5.4 hours billed is for work done in relation to Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the emails and manifests. Plaintiff also includes entries that are vague beyond usefulness, such as “work on discovery issues for Stuart J. Levine” (Doc. 192-2, at 11) and “[p]repare for and attend conference call” (Doc. 192-3, at 2). The undersigned is again unable to discern what portion of these records, if any, is relevant to the emails and manifests. Plaintiff also includes billing records that appear truly and entirely irrelevant, such as records which reflect work done on the broader case, as opposed to discovery of the emails and manifests. Among many others, in this category are billing records associated with Plaintiff's counsels’ discussion of a third-party subpoena (Doc. 192-2, at 2), review of the “economic wash rule” (Doc. 192-2, at 3), discussion of “biomedical waste issues” (Doc. 192-2, at 5), correspondence with a third party (Doc. 192-2, at 6), preparation of a Daubert motion (Doc. 192-2, at 14), mediation preparation (Doc. 192-2, at 14), and review of the notice of appearance of Richard Salazar (Doc. 276-1, at 1). As for costs, Plaintiff's requests are equally as deficient. For example, Plaintiff includes generic expenses such as simply “Westlaw research” for $15,927.00 and “Telephone Expense” for $70.64 (Doc. 192-2, at 15). These entries similarly provide the undersigned with no basis to discern which portion, if any, is attributable to Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the discovery of the emails and manifests.

*6 Yet alongside these irrelevant, duplicative, excessive, and “block-billed” entries, Plaintiff also includes billing records which are clearly relevant to Plaintiff's efforts to obtain the emails and manifests. Among these are entries associated with preparing for and attending hearings on various motions to compel and sanctions motions (see Doc. 192-2, at 3-4, 8; Doc. 192-3, at 3; Doc. 249, at 6), preparation for and taking of Rule 30(b)(6) depositions (Doc. 192-2, at 12), management of the E-Hounds forensic investigation (see Doc. 192-3, at 4; Doc. 249, at 2), and attendance of various status conferences necessitated by the ongoing efforts to obtain emails and manifests (Doc. 192-2, at 14; Doc. 192-3, at 3; Doc. 249-1, at 3).

Thus, based on the undersigned's intimate familiarity with the case and considering the limitations of Plaintiff's records, the undersigned finds Plaintiff entitled to an award of thirty percent (30%) of Plaintiff's requested fees and costs, or $113,509.15 in total. This reduction of seventy percent (70%) is reasonable in light of the nearly universal block billing and pervasive irrelevant, vague, and excessive entries contained in Plaintiff's billing and cost records. Yet while such inadequacies are present, so too are billing records reflecting efforts to obtain the discovery Plaintiff was due, made more difficult because Defendant “woefully failed to meet its discovery obligations” over the course of this litigation “by failing to timely produce the manifests and email communications” (Doc. 282, at 26). Accordingly, the undersigned determines that awarding thirty percent (30%) of the total fees and costs requested accurately captures the time spent and funds expended by Plaintiff's attorneys which would not have been incurred but for Defendant's discovery failures.

III. Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, it is hereby

ORDERED:

1. Plaintiff is awarded attorney's fees and costs in the amount of $113,509.15.

DONE AND ORDERED in Tampa, Florida, on this 8th day of May, 2023.

Footnotes

The Court rejected Plaintiff's efforts to prove spoliation at various stages of discovery, including in response to Plaintiff's Expedited Motion for Sanctions Pursuant to Rule 37(b) (Doc. 117), Plaintiff's Motion for Sanctions Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e)(2) (Doc. 131), and Plaintiff's Renewed Motion for Sanctions Pursuant to Rule 37(e) (Doc. 226) (see Doc. 158, at 107; Doc. 282, at 28). Ultimately, the Court rejected Plaintiff's spoliation sanctions due to a lack of intent to deprive Plaintiff of the electronically stored information (eliminating sanctions under Rule 37(e)(2)) and a lack of bad faith (eliminating sanctions under the court's inherent power, though it was unclear whether the court could impose sanctions under its inherent power in these circumstances) (see Doc. 282, at 11, 28 n.12).