TML Recovery, LLC v. Cigna Corp.

TML Recovery, LLC v. Cigna Corp.

2024 WL 1699349 (C.D. Cal. 2024)

February 2, 2024

Carter, David O., United States District Judge

Summary

The parties have filed multiple applications to seal documents related to a dispute between Plaintiffs and Defendants. The Court has granted in part and denied in part the parties' requests to seal documents, and has also directed the parties to meet and confer to further minimize the need for filing under seal. The Court has also addressed various categories of information, including protected health information and financial terms, that Defendants seek to redact and seal.

Additional Decisions

TML RECOVERY, LLC

v.

CIGNA CORPORATION et al

v.

CIGNA CORPORATION et al

Case No. SA CV 20-00269-DOC-JDE

United States District Court, C.D. California

Filed February 02, 2024

Counsel

Daniel J. Callahan, Michael J. Sachs, Callahan and Blaine APLC, Santa Ana, CA, Damon D. Eisenbrey, Richard T. Collins, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Washington, DC, Jennifer Shelfer, Pro Hac Vice, Landen P. Benson, Pro Hac Vice, Thomas E. Kelly, Pro Hac Vice, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Atlanta, GA, for TML Recovery, LLC.Daniel J. Callahan, Callahan and Blaine APLC, Santa Ana, CA, Michael J. Sachs, Callahan and Blaine$$, Santa Ana, CA, Damon D. Eisenbrey, Richard T. Collins, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Washington, DC, Jennifer Shelfer, Pro Hac Vice, Landen P. Benson, Pro Hac Vice, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Atlanta, GA, for Intervenor Plaintiffs MMR Services LLC, Southern California Recovery Centers Oceanside LLC, Addiction Health Alliance LLC, DR Recovery Encinitas LLC, Southern California Addiction Center Inc, 12 South LLC, Woman's Recovery Center LLC, Pacific Palms Recovery LLC.

Mazda Antia, Dylan Knopf Scott, Cooley LLP, San Diego, CA, Jamie D. Robertson, Cooley LLP, Chicago, IL, Matthew D. Caplan, Cooley LLP Library, San Francisco, CA, Sharon Soohyun Song, Cooley LLP, Los Angeles, CA, for Cigna Corporation, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company.

Claire Artemis Olin, Mazda Antia, Dylan Knopf Scott, Cooley LLP, San Diego, CA, Jamie D. Robertson, Cooley LLP, Chicago, IL, Matthew D. Caplan, Cooley LLP Library, San Francisco, CA, Sharon Soohyun Song, Cooley LLP, Los Angeles, CA, for Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company, Cigna Behavioral Health, Inc., Cigna Behavioral Health of California, Inc., Cigna Health Management, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of California Inc.

Brittany H. Alexander, Pro Hac Vice, Errol J. King, Jr., Pro Hac Vice, Katherine L. Cicardo, Pro Hac Vice, Taylor J. Crousillac, Pro Hac Vice, Phelps Dunbar LLP, Baton Rouge, LA, Jenifer C. Wallis, Munck Wilson Mandala, LLP, Los Angeles, CA, for Multiplan, Inc., Viant, Inc.

Carter, David O., United States District Judge

PROCEEDINGS (IN CHAMBERS): ORDER GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS’ APPLICATIONS TO SEAL, AND DENYING PLAINTIFFS’ EX PARTE APPLICATION FOR A NEW PROTECTIVE ORDER [351-382, 387, 390, 419]

I. Background

*1 Before the court are numerous applications to seal brought by Defendants Cigna Corporation; Cigna Health and Life Insurance Co.; Connecticut General Life Insurance Co.; Cigna Behavioral Health, Inc.; Cigna Behavioral Health of California, Inc.; Cigna Health Management, Inc.; and Cigna Healthcare of California, Inc. (collectively “Cigna”); and Defendants Viant, Inc. and MultiPlan, Inc.’s (collectively, “MultiPlan”), applications which were consolidated and revised by the parties in a joint report (Dkt. 406). Also before the Court is Plaintiffs’ ex parte application for a new protective order (Dkt. 419). As outlined below, the Court GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART the parties’ request to seal documents set forth in the joint report and DENIES Plaintiffs’ ex parte application for a new protective order.

On August 16, 2023 and August 17, 2023, the parties appeared before the Court and addressed their renewed Applications to File Documents Under Seal (Dkts. 351-53, 355-82, 390).

On August 17, the Court issued an Order directing the parties to meet and confer and file a joint report on their efforts “to further eliminate or minimize the need for filing under seal” (Dkt. 401). On August 25, 2023, the parties filed a joint status report that identified numerous documents for which the redactions should be narrowed and documents that should no longer be sealed (Dkt. 406). While Plaintiffs do not seek to seal any documents, they stress the need to keep any personal health information redacted and do not oppose any of Defendants’ sealing requests. See Dkt. 406. On November 9, 2023, the Court granted a motion by Plaintiffs to unseal documents identified in the joint report that the parties no longer seek to seal (Dkt. 456). The Court now addresses the remaining documents identified in the joint report.

II. Legal Standard

There is a right of public access to judicial records and documents. Nixon v. Warner Commc'ns, Inc., 435 U.S. 589, 597, 98 S.Ct. 1306, 55 L.Ed.2d 570 (1978). In considering motions to seal, courts recognize that “a strong presumption in favor of access is the starting point.” Kamakana v. City & County of Honolulu, 447 F.3d 1172, 1178 (9th Cir. 2006) (cleaned up). “A party seeking to seal a judicial record then bears the burden of overcoming this strong presumption by meeting the ‘compelling reasons’ standard.” Id. (quoting Foltz v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 331 F.3d 1122, 1135 (9th Cir. 2003)). Under this standard, “the party must articulate[ ] compelling reasons supported by specific factual findings that outweigh the general history of access and the public policies favoring disclosure, such as the public interest in understanding the judicial process.” Kamakana, 447 F.3d at 1178-79 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). The “compelling reasons” standard applies to documents connected to dispositive motions and other filings “more than tangentially related to the merits of a case.” Ctr. for Auto Safety v. Chrysler Grp., LLC, 809 F.3d 1092, 1101 (9th Cir. 2016). For documents connected to discovery motions unrelated to the merits of the case, however, the party need only satisfy the “less exacting ‘good cause’ standard” under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(c). Id. at 1097.

*2 Generally, sufficiently “compelling reasons” exist when “ ‘court files might have become a vehicle for improper purposes,’ such as the use of records to gratify private spite, promote public scandal, circulate libelous statements, or release trade secrets.” Id. at 1179 (quoting Nixon, 435 U.S. at 598, 98 S.Ct. 1306). But “[t]he mere fact that the production of records may lead to a litigant's embarrassment, incrimination, or exposure to further litigation will not, without more, compel the court to seal its records.” Id. Nor is it a sufficiently “compelling reason” that a party designated information as confidential pursuant to a protective order. See Capitol Specialty Ins. Corp. v. GEICO Gen. Ins. Co., No. CV 20-672-RSWL-EX, 2021 WL 7708482, at *3 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 19, 2021); Ctr. for Auto Safety, 809 F.3d at 1096; CH2O, Inc. v. Meras Eng'g, Inc., No. LA CV13-08418 JAK (GJSx), 2016 WL 7645595, at *1 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 3, 2016) (“Conclusory statements that documents are confidential do not satisfy [the compelling reasons] standard.” (citing Kamakana, 447 F.3d at 1182)).

On the other hand, “sources of business information that might harm a litigant's competitive standing” can sufficiently support a request to seal. See Ctr. for Auto Safety, 809 F.3d at 1097; see also Nixon, 435 U.S. at 598, 98 S.Ct. 1306. For example, courts have held that “license agreements, financial terms, details of confidential licensing negotiations, and business strategies” are compelling reasons to prevent competitors from leveraging this information to harm the designating parties in future negotiations. See DeMartini v. Microsoft Corp., No. 22CV-08991-JSC, 2023 WL 4205770, at *2 (N.D. Cal. June 26, 2023). Similarly, confidential profit, cost, and pricing information can also be sealed when a party establishes that the information, if publicly disclosed, could put the company at a competitive disadvantage. See e.g., Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elec. Co., 727 F.3d 1214, 1225 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“[I]t seems clear that if Apple's and Samsung's suppliers have access to their profit, cost, and margin data, it could give the suppliers an advantage in contract negotiations, which they could use to extract price increases for components.”); Torres Consulting & Law Grp., LLC v. Dep't of Energy, No. CV13-00858-PHX-NVW, 2013 WL 6196291, at *4–5 (D. Ariz. Nov. 27, 2013) (finding that the defendant conclusively established that its labor production rates were trade secrets because this information, if disclosed, “would give a competitor conclusive insight into how it could modify its business to undercut another's”).

Even where a party establishes a compelling reason or good cause to support sealing, its request must be narrowly tailored to a limited amount of information. “[R]edactions have the virtue of being limited and clear, identifying specific names or references to be kept secret.” Kamakana, 447 F.3d at 1183. Nonetheless, even when there are only specific redactions, “a broad, categorical approach” will not meet the “compelling reasons” standard. Id.; see La. Pac. Corp. v. Money Market 1 Institutional Inv. Dealer, 2013 WL 550563, at *2 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 12, 2013) (denying motion to seal because, although the plaintiff only sought to redact a limited amount of information, the plaintiff did “not allege that this information is competitively sensitive, contains a trade secret, could be used for an improper purpose, or in fact, any reason ... for why the information should be sealed”).

III. Discussion

Defendants’ requests to redact and seal documents can be sorted into several categories of information: protected health information, identifying information of Defendants’ clients, financial terms of contractual agreements, cost containment fees, and descriptions of several of Defendants’ business strategies or methodologies. The Court addresses each of these categories of information below.

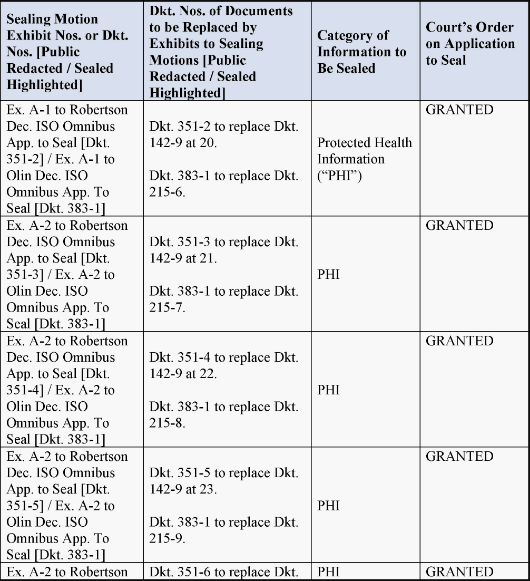

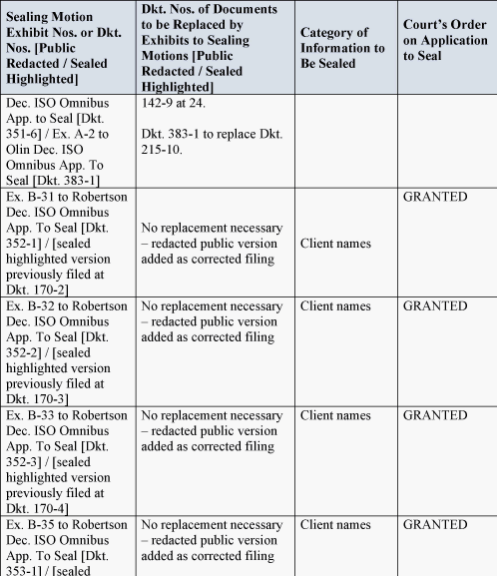

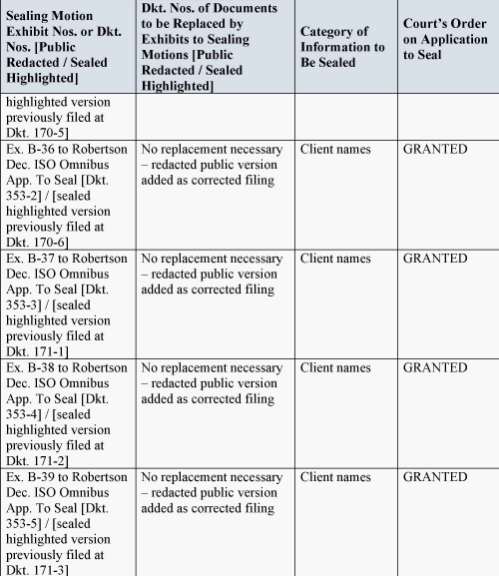

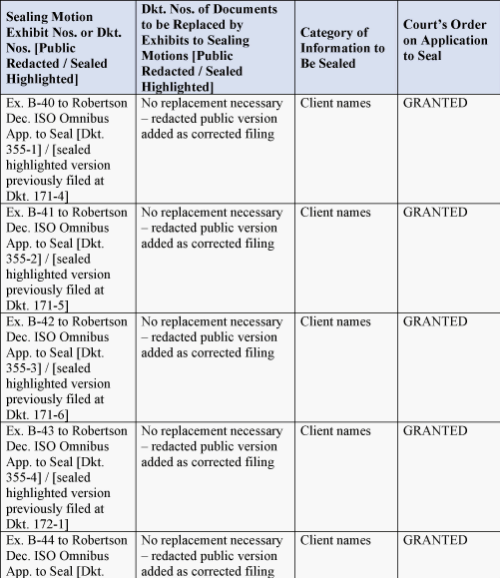

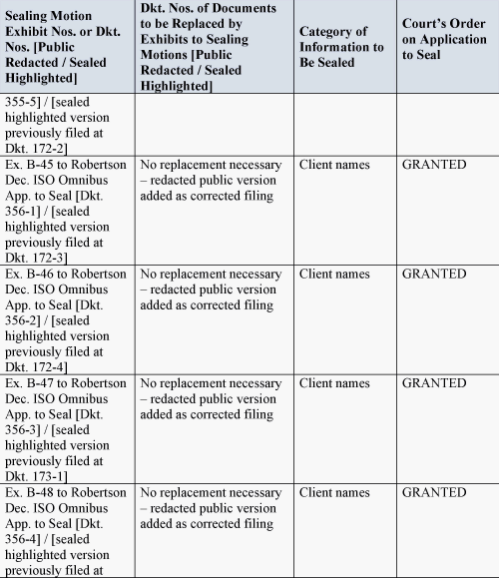

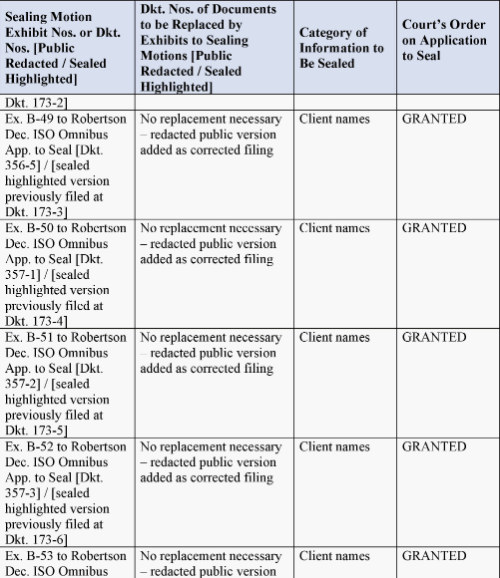

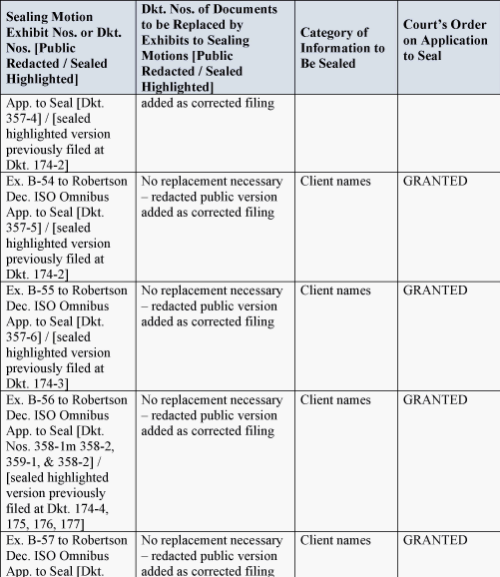

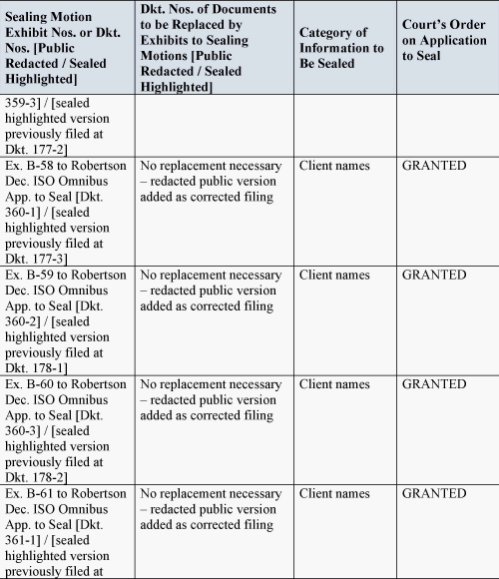

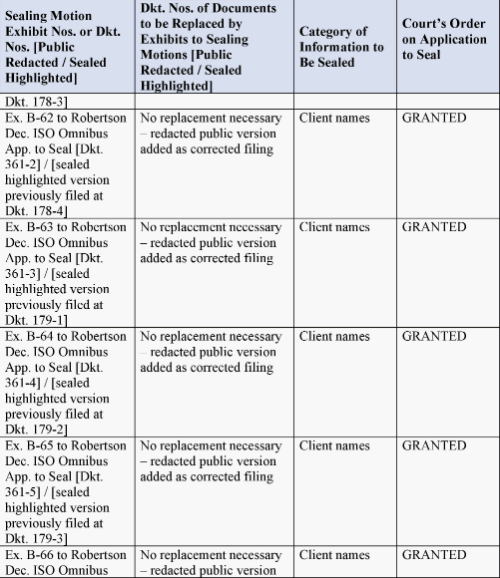

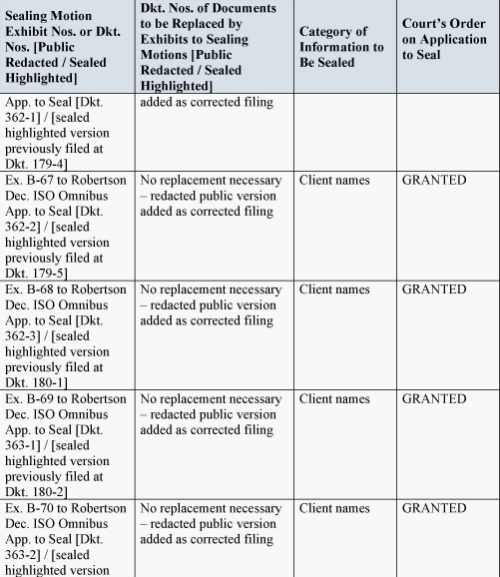

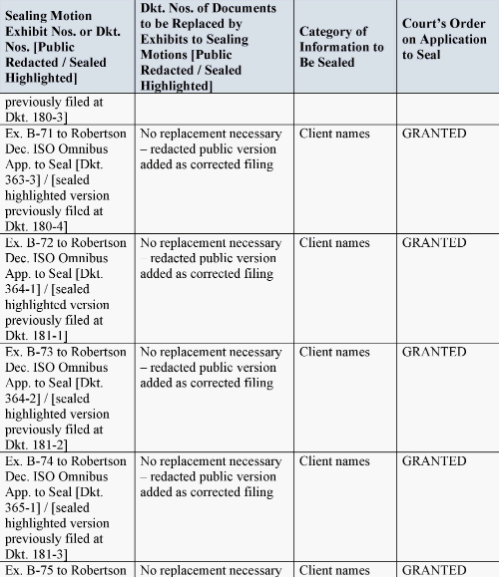

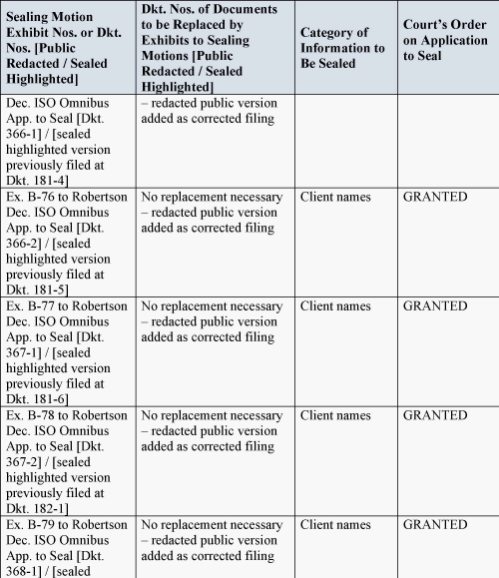

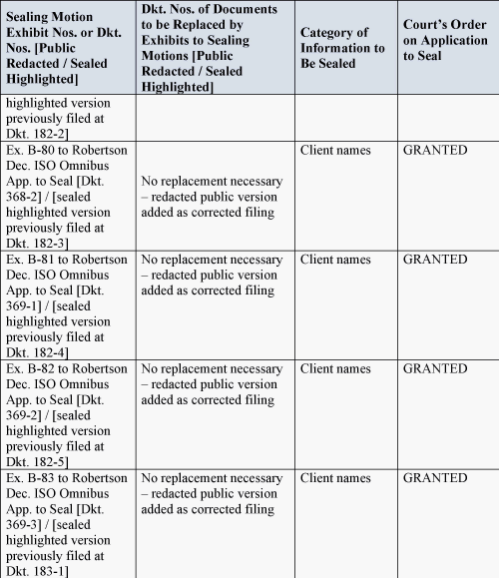

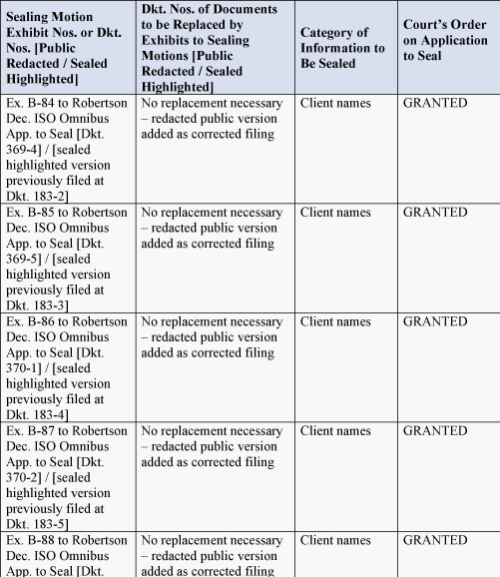

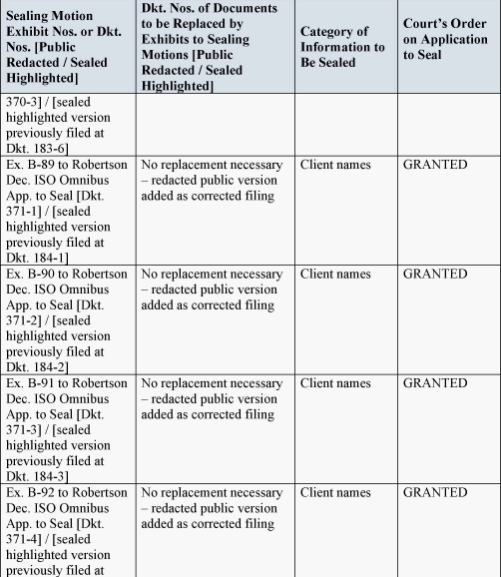

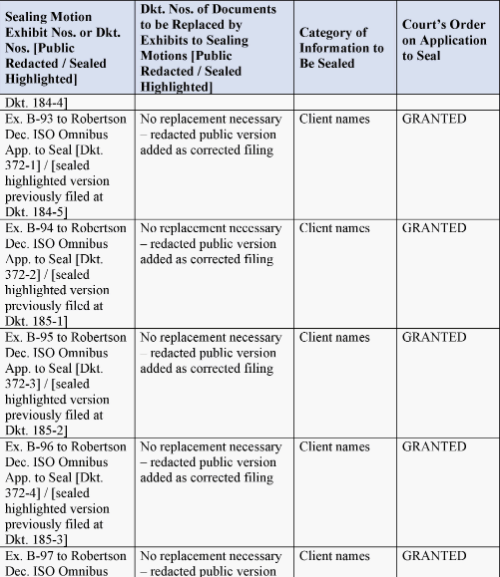

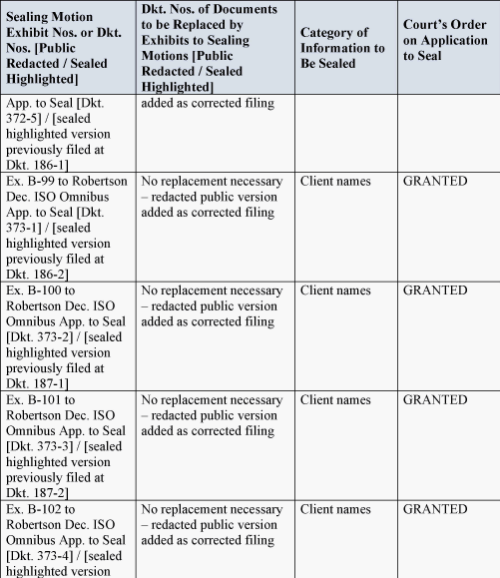

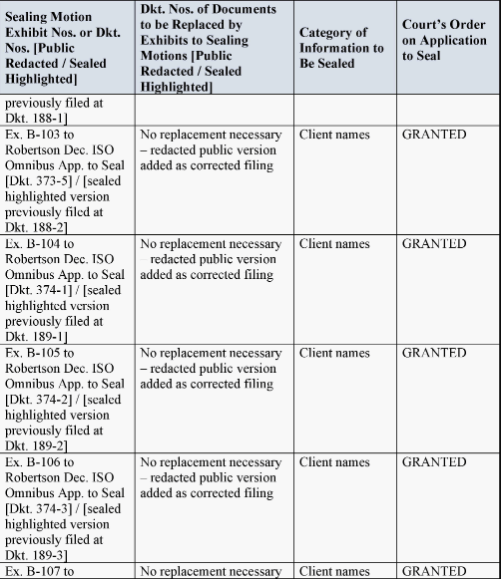

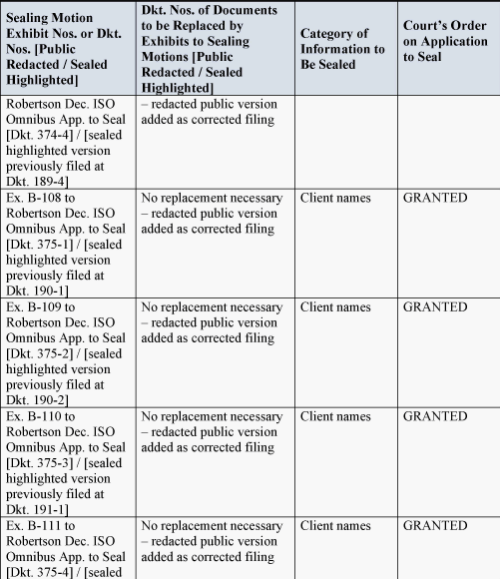

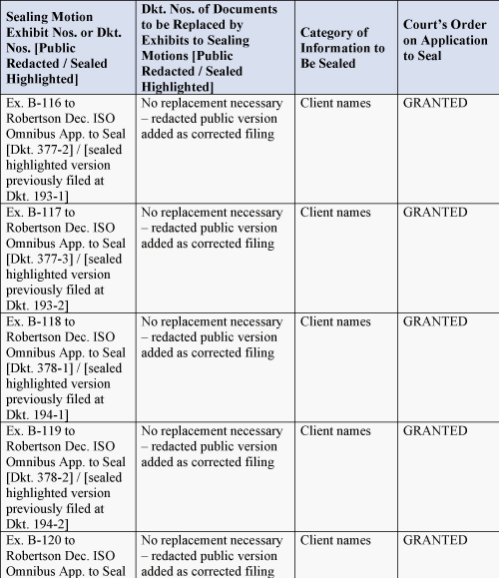

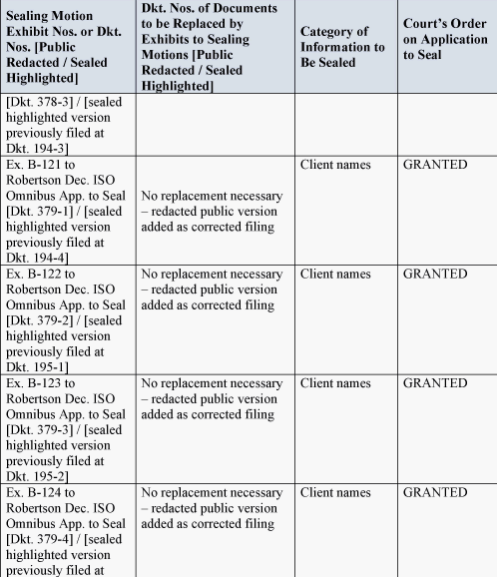

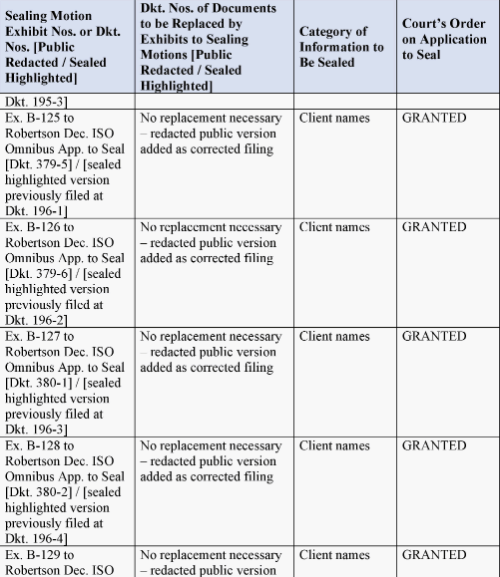

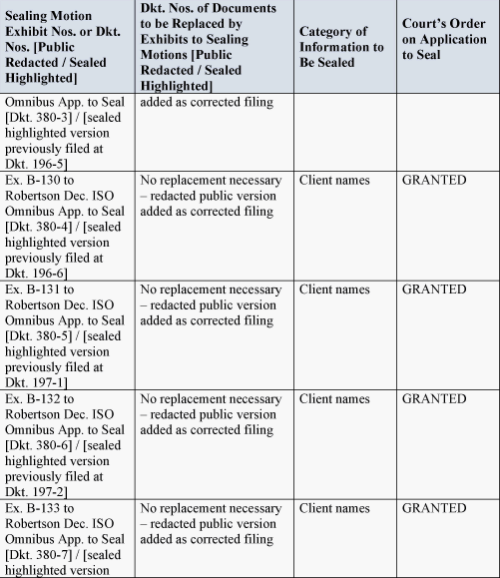

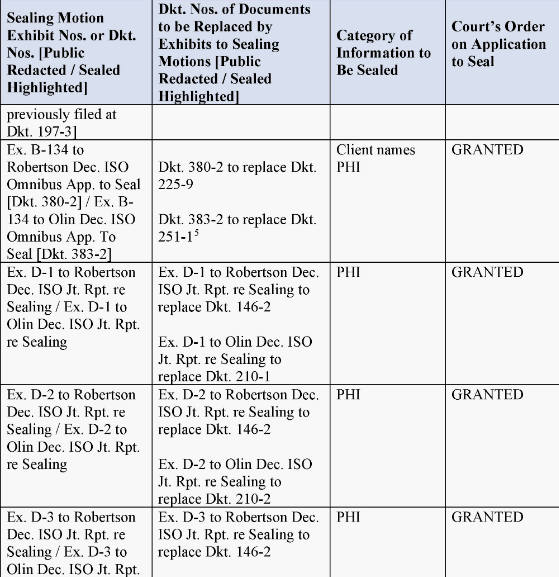

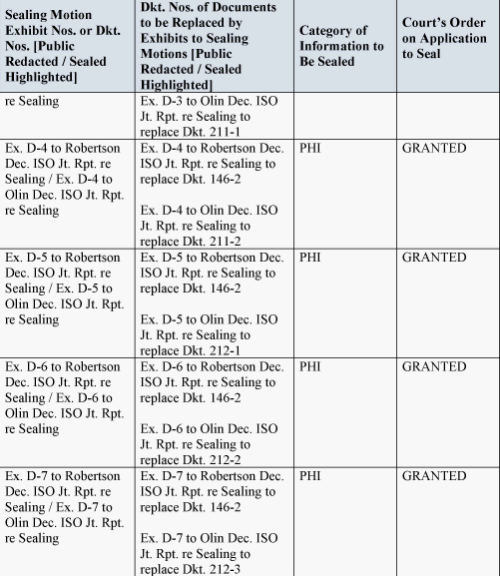

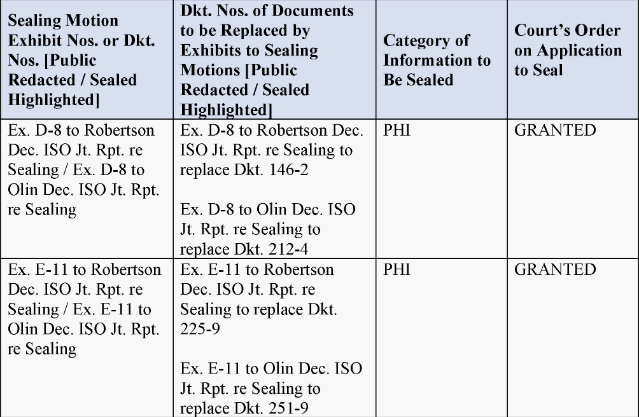

A. PHI & Client names

*3 Defendants contend that numerous documents contain confidential protected health information (PHI) under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). A review of the documents identified in the below chart as containing PHI confirms the proposed redactions are of information protected by HIPAA. Consistent with its prior Order (Dkt. 348), the Court GRANTS Cigna's request to redact any PHI as set out below in Table A. Defendant Cigna also seeks to redact client names and other identifying information from the documents identified below. Consistent with its prior Order (Dkt. 348), the Court GRANTS Cigna's request to redact client names and identifying information from the documents identified in Table A.

B. ASO Agreement Financial Terms, Cost Containment Fees, Descriptions of Cross-Walking Methodology, and Multi-Plan's Business Strategies and Pricing Methodologies

Cigna next seeks to redact specific financial terms from a number of Administrative Services Only (ASO) Agreements. As part of Cigna's regular business activities, Cigna negotiates plan terms with plan sponsors and signs contractual agreements that set out the terms under which Cigna will service the plan sponsor's health benefit plan. Declaration of Mario Vangeli in Support of Omnibus Application to Seal (“Vangeli Dec.”) (Dkt. 387) ¶ 3. The terms of these agreements, including the fee schedules, vary from client to client. Id. ¶ 4. Cigna therefore asserts these are highly confidential and would harm their competitive standing if publicly released. Id.

Defendants also seek to seal cost containment fee information, both specific dollar amounts and percentages. As part of Cigna's cost containment program, Cigna receives a percentage of the savings it achieves through the use of Cigna's and MultiPlan's cost containment services which include, among other things, repricing and negotiation. Vangeli Decl. ¶ 5. The individual “cost containment” fees are negotiated between Cigna and MultiPlan or Cigna and other vendors. Cigna uses multiple cost-containment vendors. Id. Defendants assert that if cost-containment fee data were disclosed, Cigna's competitors and others, such as vendors who compete with MultiPlan, Plans, and providers, could use the data to ascertain the terms of contractual arrangements between Cigna and its customers and then use that information to underbid Cigna in negotiations with those or other clients. Id. ¶ 6. MultiPlan also seeks to redact cost containment fees and percentages from several additional exhibits.

Cigna also seeks to seal portions of expert reports and deposition transcripts that describe how Cigna developed pricing for certain types of substance use disorder treatment service claims, including the appropriate comparator levels of care and Medicare procedure codes. Cigna refers to this as their “cross-walking methodology.” Cigna argues that the specifics of how it developed such pricing and the analysis required to do so is proprietary and that if other service providers had access to such information they could use it in negotiations with cost containment vendors, like MultiPlan, to seek to obtain higher rates. See Dkt. 351 at 23.

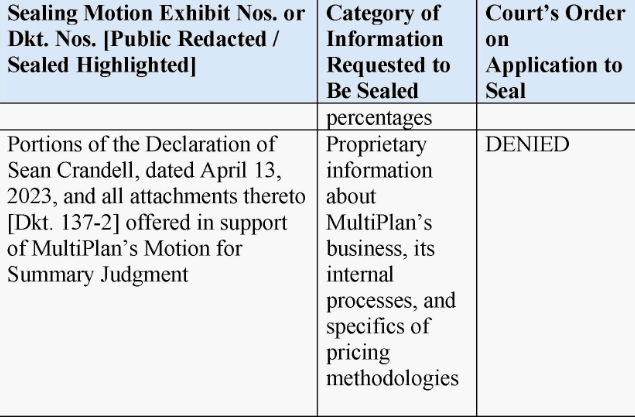

Multiplan additionally seeks to redact portions of a deposition transcript and attached “whitepapers” that describe the various components, source data, and logic used by MultiPlan's proprietary services and methodology. See Declaration of Marjorie Wilde (Dkt. 390-1) ¶ 15. MultiPlan asserts that if a competitor gained access to this information, the competitor could potentially reverse engineer MultiPlan's pricing methodologies, thus harming their business. Id.

In order to justify sealing these documents under the applicable compelling reasons standard, Cigna “must articulate[ ] compelling reasons supported by specific factual findings that outweigh the general history of access and the public policies favoring disclosure, such as the public interest in understanding the judicial process.” Kamakana, 447 F.3d at 1178-79 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). Essentially, the Court must balance the interests of the public against those of the party seeking to seal judicial records. Ctr. for Auto Safety, 809 F.3d at 1097.[1]

*4 The Court is skeptical that all proposed redactions of the expert reports and deposition transcripts that discuss cost containment measures and the cross-walking methodology would harm Defendants’ competitive standing if released. A review of these documents demonstrates that sections of the proposed redactions are generalized and at times overlap with publicly available information. For example, Defendants seek to seal portions of a deposition transcript describing how Cigna's cost containment program only charges a fee if successful, something Cigna states on its website advertising its cost containment program.[2] Declaration of Jamie Robertson ISO Sealing, Ex. E-6.

In their supporting declarations, Cigna and MultiPlan have demonstrated, however, that they likely have compelling reasons to redact many of the individually negotiated documents, such as ASO Agreements, as “sources of business information that might harm a litigant's competitive standing.” Ctr. for Auto Safety, 809 F.3d at 1097. Under governing Ninth Circuit precedent, this does not automatically entitle Defendants to redact these documents. Instead, as compelling reasons exist here that could justify redaction, the Court then considers whether these reasons outweigh the public interest in access to and understanding of the judicial process. Kamakana, 447 F.3d at 1178-79.[3]

It is a long-standing common law principle that judicial records are public records, which by definition are presumed to be accessible by the public. The public right of access is premised upon the recognition that public monitoring of the courts fosters important values of transparency, respect for the legal system and rule of law, and accuracy of fact-finding and judicial proceedings. Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 100 S.Ct. 2814, 65 L.Ed.2d 973 (1980). “Though its original inception was in the realm of criminal proceedings, the right of access has since been extended to civil proceedings because the contribution of publicity is just as important there.” Grove Fresh Distributors, Inc. v. Everfresh Juice Co., 24 F.3d 893, 897 (7th Cir. 1994) (internal citation omitted). One court has described the public's right to examine judicial records as “fundamental to a democratic state.” United States v. Mitchell, 551 F.2d 1252, 1258 (D.C. Cir. 1976), rev'd on other grounds sub nom. Nixon v. Warner Communications, Inc., 435 U.S. 589, 98 S.Ct. 1306, 55 L.Ed.2d 570 (1978).

Equally important, as the Ninth Circuit has emphasized, is the public's right to know how its resources are being used. “Courts are funded by the public, judges are evaluated by the public, officials who appoint and approve judges are voted on by the public, and the laws under which parties sue may be refined, rescinded, or strengthened based on the public's views of the ways in which they play out in court.” Courthouse News Serv. v. Planet, 947 F.3d 581, 592 (9th Cir. 2020) (internal citations omitted).

This presumption of public access is at its strongest when it comes to judicial decisions and the underlying documents on which a judge bases a decision. The issuance of public opinions is core to the transparency of the court's decision-making process. In re Leopold to Unseal Certain Elec. Surveillance Applications & Ords., 964 F.3d 1121, 1128 (D.C. Cir. 2020) (internal citation omitted). Courts have found the public interest relatively weak when redacted information in sealed documents was not relevant to the resolution of a motion before the court. See, e.g., Loc. 640 Trustees of IBEW & Arizona Chapter NECA Health & Welfare Tr. Fund v. Cigna Health & Life Ins. Co., No. CV-20-01260-PHX-MTL, 2020 WL 6273409, at *2 (D. Ariz. Oct. 26, 2020).

*5 Here, the information Defendants seek to seal is relevant and critical to the Court's consideration of the parties’ cross-motions for summary judgment (Dkts. 138, 139, 141).[4] Cigna, for example, in its motion for summary judgment, argues that the fees it receives as part of its cost containment program do not reflect a conflict of interest, that these fees are included in the ASO Agreements, and that its cross-walking methodology was consistent with the terms of its provider plans. See Dkt. 141 at 12-16. Similarly, MultiPlan's pricing methodologies are a central focus of Plaintiffs’ complaint and of MultiPlan's motion for summary judgment. See MultiPlan's Motion for Summary Judgment (Dkt. 139). Understanding the financial terms of the ASO Agreements, how Defendants’ cost containment programs work, how cross-walking operates in relation to the terms of provider plans, and the architecture of MultiPlan's pricing methodology will be essential to the Court's rulings on these motions. This understanding would also be necessary background for any member of the public seeking to read and understand the Court's orders. As this case concerns health insurance and healthcare providers, matters of widescale public concern, these documents are likely to be of interest to many individuals besides Defendants’ competitors. The Court therefore finds the public interest in access here strong.

In weighing the public's interest in access to the courts with the parties’ interest in sealing certain information, the Court also considers the potential harm of releasing that information. In doing so, the Court finds the Fifth Circuit's opinion in Binh Hoa Le v. Exeter Fin. Corp., 990 F.3d 410 (5th Cir. 2021) instructive. In discussing how district courts routinely grant sprawling sealing applications stipulated to by the parties in order to relieve administrative burdens, the Fifth Circuit commented,

“Certainly, some cases involve sensitive information that, if disclosed, could endanger lives or threaten national security. But increasingly, courts are sealing documents in run-of-the-mill cases where the parties simply prefer to keep things under wraps.”

Binh Hoa Le, 990 F.3d at 417–18. Disclosure of a limited sub-set of Defendants’ contracts and business strategies, documents central to resolving the parties’ disputes before this court, is not the sort of disclosure that could endanger lives or threaten national security. The potential disadvantages are relatively minor. Public scrutiny is a cost that private litigants routinely must bear in exchange for access to public courts.

Having reviewed the documents and considered the arguments put forth by the parties, the Court finds on balance that Defendants’ interests in keeping the portions of these documents discussed here under seal do not outweigh the public right of access.

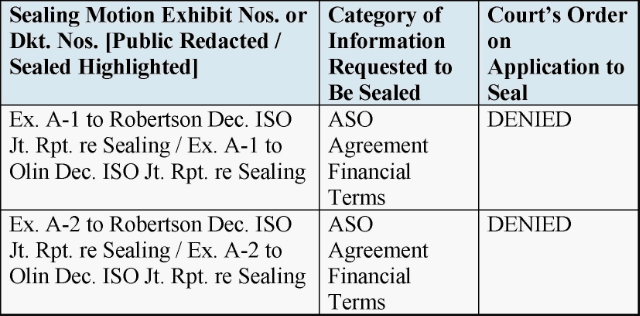

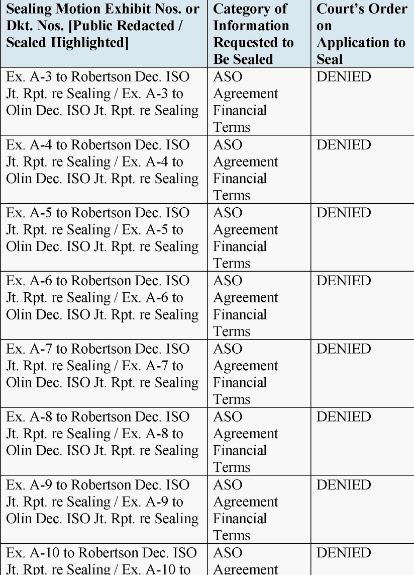

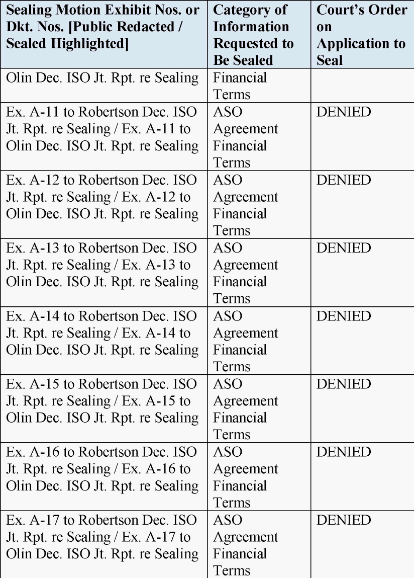

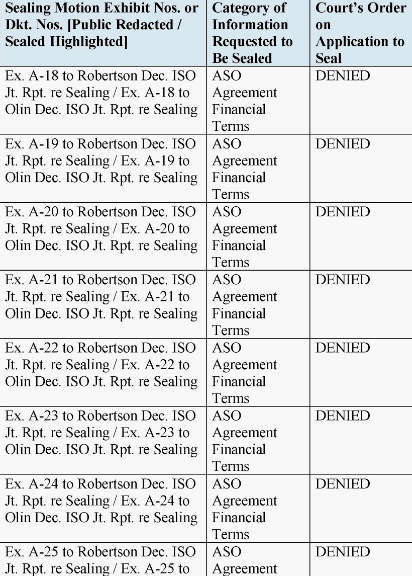

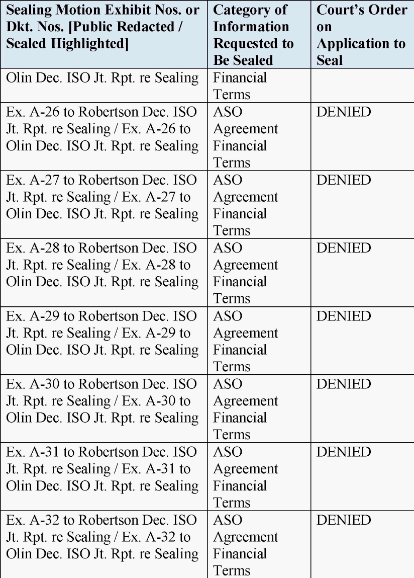

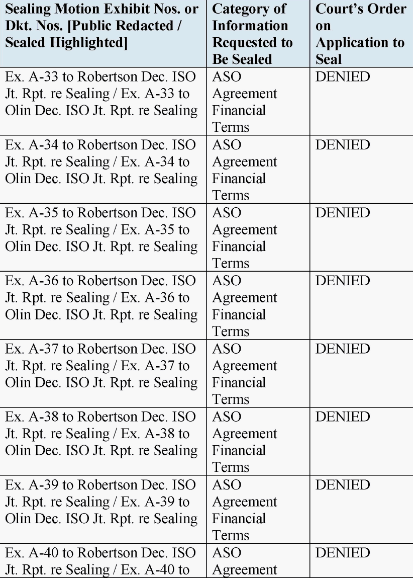

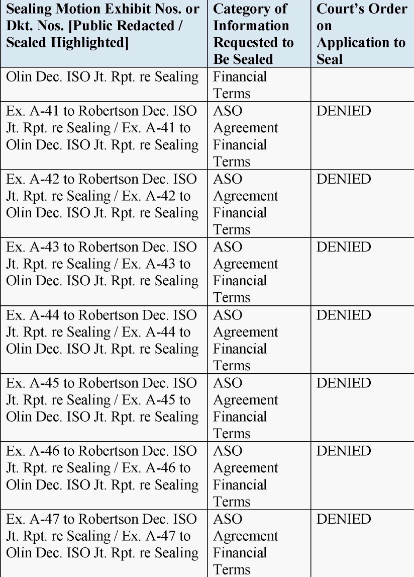

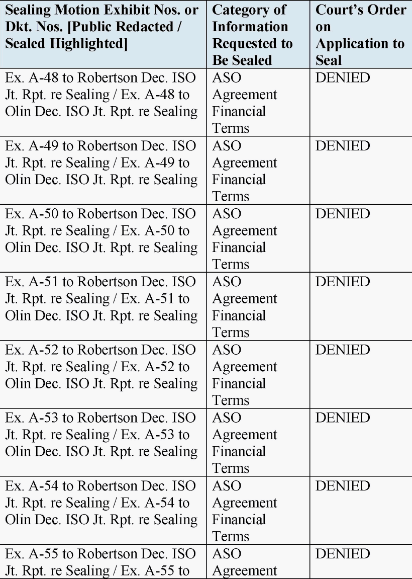

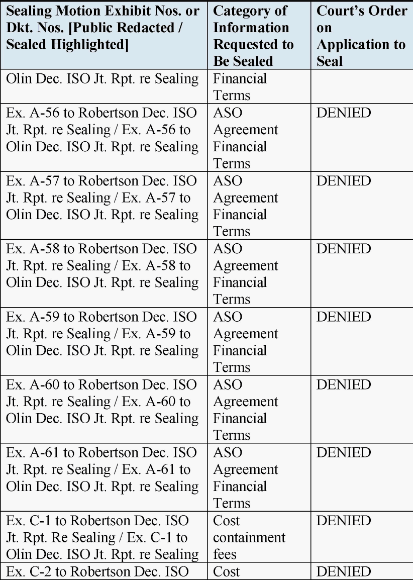

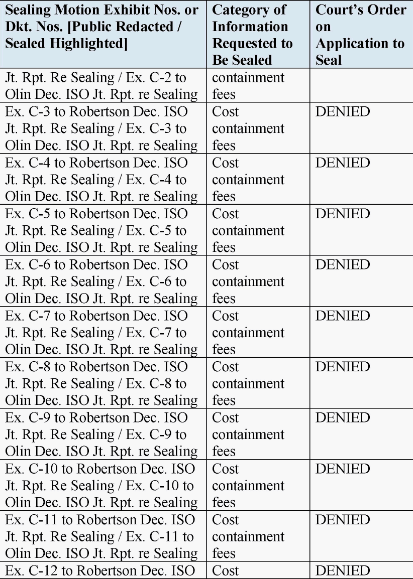

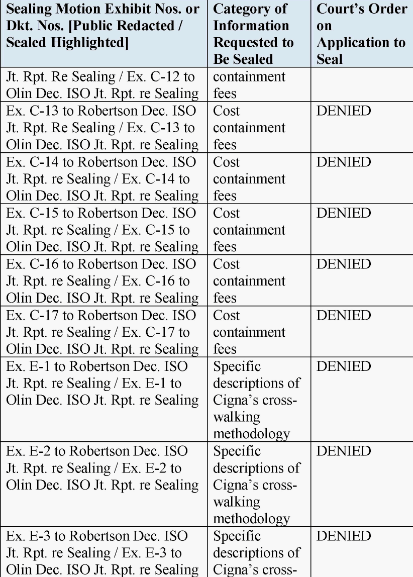

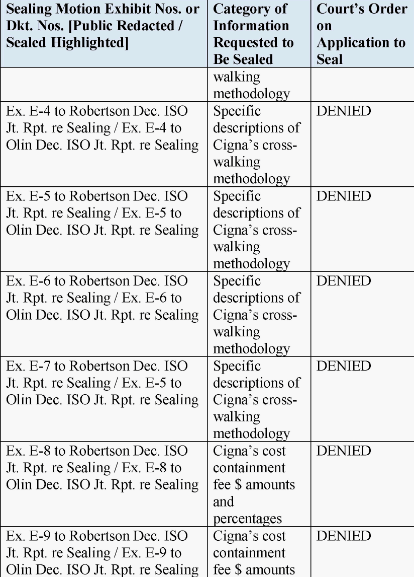

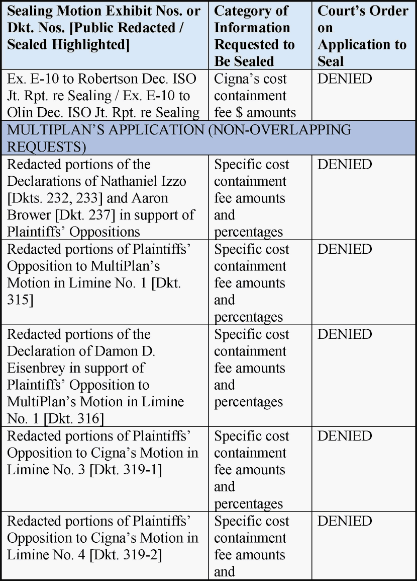

The Court therefore DENIES Cigna's and MultiPlan's requests to redact financial terms of ASO Agreements, cost containment fee dollar amounts and percentages, descriptions of Cigna's cross-walking methodology, and whitepapers and portions of testimony discussing MultiPlan's pricing methodologies, as detailed in the below chart (Table B).

C. Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Application for Protective Order

On September 7, 2023, Plaintiffs filed an ex parte application for a new protective order (Dkt. 419). Plaintiffs believed, based on discussions at the hearings on August 16-17, 2023, that the Court vacated the existing stipulated protective order (SPO) (Dkt. 19).

Defendants opposed the application (Dkt. 447), arguing that the application is unwarranted as the Court did not vacate the existing SPO at the hearing. The Court clarifies that it did not vacate the existing SPO at the hearing. Instead, the Court determined that the rules and case law regarding sealing govern the public disclosure of documents in this case, not the SPO. Thus, the existing SPO (Dkt. 19) is still valid. The Court DENIES Plaintiff's ex parte application, finding it unnecessary.

IV. DISPOSITION

The Court GRANTS IN PART Defendants’ Requests to Seal, as detailed in Table A and DENIES IN PART Defendants’ Requests to Seal, as detailed in Table B. The parties are directed to file unredacted copies of the documents identified in Table B. The Court DENIES Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Application for a new protective Order.

TABLE B:

Footnotes

See also DeMartini v. Microsoft Corp., No. 22-CV-08991-JSC, 2023 WL 4205770, at *2 (N.D. Cal. June 26, 2023) (the court “balances the public's understanding of the judicial process against such confidential information within the context of the gravamen of this case.”); Epic Games, Inc. v. Apple Inc., No. 4:20-cv-05640-YGR, 2021 WL 1925460, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 30, 2021) (balancing confidentiality of third-party information “with the [c]ourt's ultimate resolution of the instant dispute which should be transparent in its analysis”).

See https://secure.cigna.com/employers/cost-control/cost-containment (“Additional benefits of our cost containment program ... Never charge a fee unless the programs are successful”)

See also Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c) advisory committee's note to 1970 amendment (In the context of protective orders, “courts have not given trade secrets automatic and complete immunity against disclosure, but have in each case weighed their claim to privacy against the need for disclosure.”).

The Court has not yet ruled on these motions and will address them in a separate order.

PHI in the body of the text on p. 101 of Dkt. 383-2 appears to have been left unredacted by mistake and needs to be redacted. The parties are ordered to ensure other PHI included in the documents has been fully redacted.