Dunsmore v. San Diego Cnty. Shertiff's Dept.

Dunsmore v. San Diego Cnty. Shertiff's Dept.

2024 WL 5161947 (S.D. Cal. 2024)

December 18, 2024

Leshner, David D., United States Magistrate Judge

Summary

The parties are disputing the confidentiality of certain ESI in a class action lawsuit regarding conditions in San Diego County jails. The court has ruled that documents generated by the Sheriff's Department's Critical Incident Review Board will remain confidential pending a ruling from the Ninth Circuit. However, medical records of incarcerated persons will be de-designated with redactions to balance the public interest and the privacy of the individuals. The parties also disagree on whether custody records of deceased individuals can be de-designated.

Additional Decisions

DARRYL DUNSMORE, et al., Plaintiffs,

v.

SAN DIEGO COUNTY SHERIFF'S DEPARTMENT, et al., Defendants

v.

SAN DIEGO COUNTY SHERIFF'S DEPARTMENT, et al., Defendants

Case No.: 20-cv-406-AJB-DDL

United States District Court, S.D. California

Filed December 18, 2024

Leshner, David D., United States Magistrate Judge

ORDER GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO MAINTAIN CONFIDENTIALITY and GRANTING MOTIONS TO SEAL

*1 Before the Court is Defendants' motion to maintain the confidentiality of documents produced in discovery and designated as “Confidential” under the Protective Order. Dkt. No. 724. Having considered the parties briefing and their argument at the motion hearing on December 5, 2024, the motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. The parties also move to seal various exhibits submitted in connection with the Motion. Dkt. Nos. 726, 738. For the reasons stated on the record during the December 5 hearing, the motions to seal are GRANTED.

I.

BACKGROUND

Plaintiffs are a certified class of individuals “who are now, or will be in the future, incarcerated in any of the San Diego County Jail facilities.” Dkt. No. 435 at 10. Their Third Amended Complaint asserts multiple causes of action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against the County of San Diego and other defendants seeking declaratory and injunctive relief to “remedy the dangerous, discriminatory, and unconstitutional conditions in the Jail.” Dkt. No. 231, ¶ 4.

The stipulated Protective Order in this case (Dkt. No. 255) allows the parties to designate materials produced in discovery as “CONFIDENTIAL” or “CONFIDENTIAL – FOR COUNSEL ONLY.” The Protective Order limits the dissemination of any materials so designated. Dkt. No. 255. Plaintiffs requested that Defendants de-designate certain materials designated as confidential that are incorporated into Plaintiffs' expert reports. Defendants agreed to de-designate certain materials but, with respect to the remaining materials, Defendants seek a ruling that the documents are properly designated as confidential under the Protective Order, and thereby maintain the existing limits on Plaintiffs' ability to disseminate those documents.

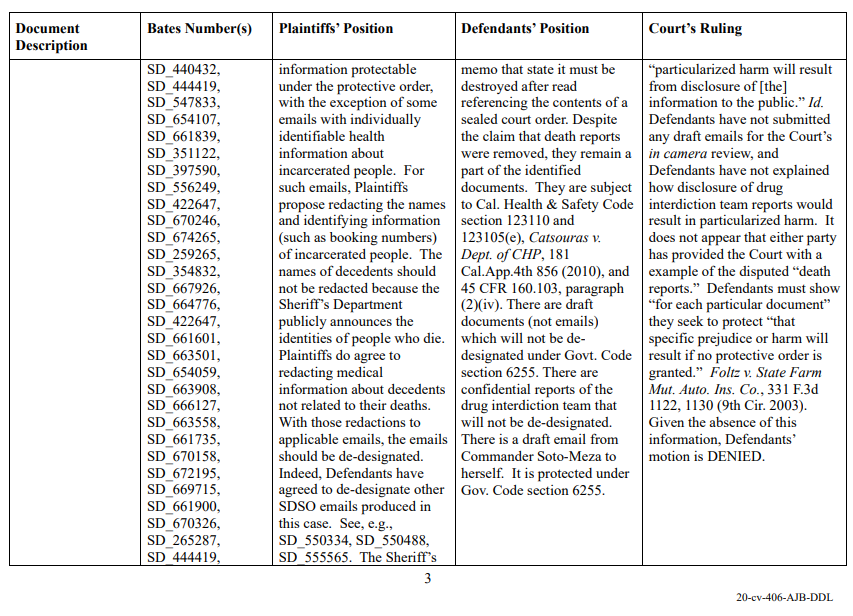

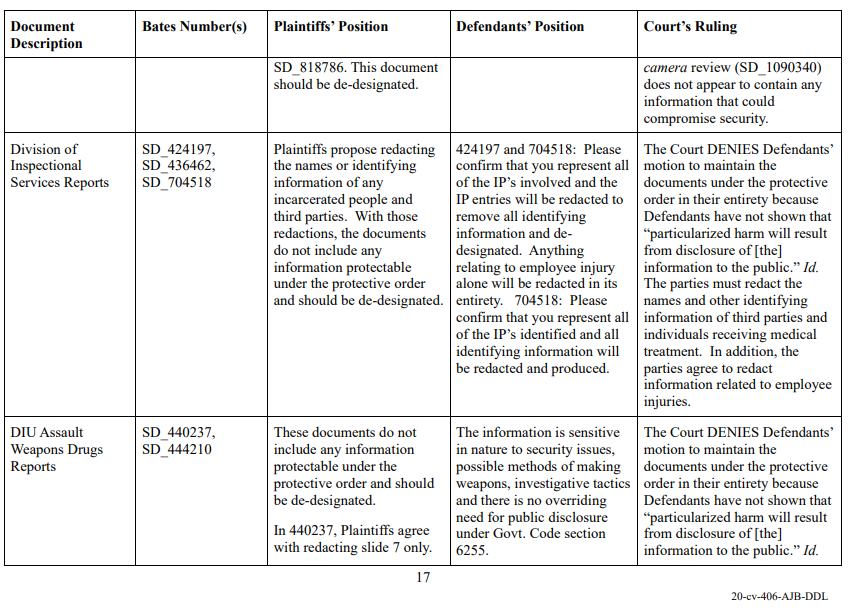

Defendants' motion includes a chart summarizing the parties' positions with respect to categories of documents Plaintiffs contend should not be subject to the Protective Order (e.g., “SDSO Inspection Reports” and “Grievances”). Dkt. No. 724 at 15-25. The chart also identifies the disputed documents by Bates Number. Id. In the motion, Defendants grouped those categories into broader issues (e.g., “Individual ‘medical records’ ” and “Decedent Records”). Id. at 3-11. The parties subsequently filed a revised chart and provided the Court with examples of the disputed documents for in camera review. Dkt. No. 737.

II.

DISCUSSION

A. Legal Standards

“As a general rule, the public is permitted access to litigation documents and information produced during discovery.” In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland in Or., 661 F.3d 417, 424 (9th Cir. 2011). “If a party takes steps to release documents subject to a stipulated [protective] order, the party opposing disclosure has the burden of establishing that there is good cause to continue the protection of the discovery material.” Id.; see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c)(1) (“The court may, for good cause, issue an order to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression or undue burden or expense.”). “A party asserting good cause bears the burden, for each particular document it seeks to protect, of showing that specific prejudice or harm will result if no protective order is granted.” Foltz v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 331 F.3d 1122, 1130 (9th Cir. 2003).

*2 The good cause inquiry proceeds in two steps. First, the Court “must determine whether particularized harm will result from disclosure of information to the public.” In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland, 661 F.3d at 424. “Broad allegations of harm, unsubstantiated by specific examples or articulated reasoning, do not satisfy the Rule 26(c) test.” Id. Second, “if the court concludes that such harm will result from disclosure of the discovery documents, then it must proceed to balance the public and private interests to decide whether maintaining a protective order is necessary.”[1] Id. Where both factors “weigh in favor of protecting the discovery material,” “a court must still consider whether redacting portions of the discovery material will nevertheless allow disclosure.” Id. at 425.

B. Disputed Issues

This Order addresses the broader issues raised in Defendants' motion and also incorporates the parties' chart with rulings for the documents provided to the Court in camera.

1. CIRB Reports

The Court previously held that Defendants had not met their burden to establish that documents generated by the San Diego Sheriff's Department's Critical Incident Review Board (“CIRB”) are protected in their entirety by either the attorney-client privilege or the work product doctrine, and ordered Defendants to produce the documents with limited redactions. Dkt. Nos. 468, 507. This issue is before the Ninth Circuit in County of San Diego v. Greer, Court of Appeals No. 23-55607. Accordingly, the Court GRANTS Defendants' motion to maintain the CIRB Reports under the Protective Order without prejudice to Plaintiffs' ability to seek further relief following the Ninth Circuit's ruling in Greer.

2. Medical Information of Incarcerated Persons

Defendants contend that documents containing medical information regarding living incarcerated persons should remain subject to the Protective Order in their entirety. Plaintiffs agree that personally identifying information should be redacted but argue that the records should be otherwise not be subject to the Protective Order.

At step one of the “good cause” analysis, the Court finds that disclosure of unredacted records pertaining to medical care would result in particularized harm to the individuals receiving care. See In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland, 661 F.3d at 424. No party argues otherwise, as evidenced by Plaintiffs' proposal to redact the identifying information of living incarcerated persons. At step two, the Glenmede factors support disclosure of information pertaining to medical care at the San Diego County jails generally given that the provision of such care is “relevant to public safety” and “implicate[s] issues important to the public.” Johnson v. Coos Cnty., No. 6:19-CV-01883-AA, 2023 WL 3994287, at *3 (D. Or. June 14, 2023) (unsealing motion for sanctions with exhibits containing information regarding private entity's provision of healthcare to incarcerated persons).

The question, then, is “whether redacting portions of the discovery material will nevertheless allow disclosure.” In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland, 661 F.3d at 425. The Court concludes that redacting incarcerated person names and other identifying information from medical records will properly balance the public interest in obtaining information regarding the provision of medical care at the jails with the private interest of incarcerated persons in keeping their medical information confidential. See id. at 424 (directing bankruptcy court to redact name of retired priest from records relating to church sex abuse scandal because “nothing in the record indicates that he continues working in the community” and “victims can know that they are not alone, and church officials' complicity in the abuse can be revealed, without disclosing the identity of accused priests”). This conclusion is bolstered by caselaw holding that, in the context of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the California Confidentiality of Medical Information Act, “[r]edacting individual patient identification information addresses the legal restrictions on disclosure of patient health information.” Lifschutz v. Am. Bd. of Surgery, No. EDCV141762FMOSPX, 2015 WL 13916604, at *4 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2015). Subject to such redactions, the motion to maintain the confidentiality of these records is DENIED.

4. Custody Records of Decedents

*3 The parties dispute whether custody records of individuals who died in Sheriff's Department custody can be de-designated. In another case involving a death in a County jail, the Court determined that emails containing the names of individuals who died in San Diego County jails should not be subject to a protective order. See Est. of Serna v. Cnty. of San Diego, No. 20-CV-2096-BAS-DDL, 2024 WL 3564460 (S.D. Cal. May 13, 2024). The Court relied, in part, on information provided by the County that its “current policy is to release certain information regarding in-custody deaths, including the decedents' names” and that the County had not “established a particularized harm that would result from releasing the three emails with in-custody death information to the public.” Id. at *4.

Here, Defendants contend the privacy rights of family members of individuals who died in custody weigh against de-designating the documents pertaining to the deaths. But Defendants do not address the fact that the County already releases information regarding in-custody deaths, including decedents' names, as represented in Estate of Serna. Id. Additionally, under a recently enacted California law, “any record relating to an investigation conducted by the local detention facility involving a death incident maintained by a local detention facility shall not be confidential and shall be made available for public inspection pursuant to the California Public Records Act ....” Cal. Penal Code § 832.10(b). Given that the County releases information regarding in-custody deaths and that § 832.10(b) requires the release of records pertaining to investigations of in-custody deaths, the Court concludes, consistent with its ruling in Estate of Serna, that the County has not shown a particularized harm that would result from releasing that same information. Est. of Serna, 2024 WL 3564460, at *4. Moreover, the generalized concerns regarding family member privacy rights do not establish good cause for maintaining the documents' confidentiality under Ninth Circuit law. See id. (citing In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland in Or., 661 F.3d at 424 (“[b]road allegations of harm, unsubstantiated by specific examples or articulated reasoning” insufficient to demonstrate good cause)).

The precise scope of the records at issue is unclear because Defendants' brief refers to “medical records of a deceased person” (Dkt. No. 724 at 5); however, the exemplars submitted for in camera review include biographical information, booking documents and court documents but not include medical records. See Dkt. No. 737 at 3 (Exh. H, SD 704804-704813). It is Defendants' burden to establish “specific prejudice or harm” that would result from disclosure “for each particular document [they] seek[ ] to protect.” Foltz, 331 F.3d at 1130. That Defendants did not submit medical records for the Court's review weighs against a finding of good cause. Even assuming the documents contain decedents' medical information, there is a strong public interest in information regarding in-custody deaths, Johnson, 2023 WL 3994287, at *3, and “an individual's privacy rights with regard to medical records is diminished after death.” Marsh v. Cnty. of San Diego, No. CIV. 05CV1568 JLS AJB, 2007 WL 3023478, at *3 (S.D. Cal. Oct. 15, 2007). As such, the Court agrees with Plaintiffs that redaction of “information about specific prior diagnoses or medications” unrelated to the death (Dkt. No. 728 at 10) strikes the appropriate balance between the public's interest in the information and individual privacy concerns. Subject to such redactions, the motion to maintain the confidentiality of these records is DENIED.

5. Identities of Incarcerated Persons

*4 Plaintiffs propose to redact the names of incarcerated persons from all the records they seek to remove from the Protective Order. But Plaintiffs have neither shown any particularized harm that would result from the disclosure of incarcerated person names generally nor explained how the balancing of public and private interests would weigh in favor of not disclosing names. See, e.g., Doe v. Bonta, 101 F.4th 633, 637 (9th Cir. 2024) (names and other biographical data “do[ ] not implicate the right to informational privacy”). As discussed at the December 5 hearing, the parties may elect to redact incarcerated person names from information that is de-designated under the Protective Order prior to releasing any such information, but the present record does not support a finding of good cause to require redaction of incarcerated person names.

6. Identities of County Employees

Defendants assert that good cause exists to redact personal information, including names, of County employees identified in documents produced in discovery, citing the “right of privacy of the employees in performing their job duties” and arguing that disclosure “serves no purpose other than trying the case through the press.” Dkt. No. 724 at 8. Plaintiffs respond that names of peace officers are not protected personnel records under California law and that such information is also subject to disclosure under Penal Code § 832.10(b). Plaintiffs further point out that prior filings in this case have included the names of County employees. Dkt. No. 728 at 12 (citing Dkt. No. 621-2).

There exists “a right to informational privacy under the Fourteenth Amendment stemming from an individual's interest in avoiding disclosure of personal matters.” Doe, 101 F.4th at 637. However, “biographical data,” such as names, “does not implicate the right to informational privacy.” Id. (affirming dismissal of action challenging California statute authorizing disclosure of identifying information about purchasers of firearms and ammunition and persons holding permits to carry concealed weapons). California law does protect “personnel records of peace officers and custodial officers” subject to certain exceptions. See Cal. Penal Code § 832.7. However, peace officers' names do not constitute “personnel records,” Comm'n on Peace Officer Standards & Training v. Superior Ct., 42 Cal. 4th 278, 289 (2007), and thus they may be publicly disclosed unless such disclosure would “link those names to any confidential personnel matters or other protected information.” Long Beach Police Officers Assn. v. City of Long Beach, 59 Cal. 4th 59, 73 (2014). Based on the foregoing authorities, the Court concludes that Defendants' blanket request to redact the name of every County employee from the discovery materials irrespective of the type of record does not find support in federal or state law.[2]

At the December 5 hearing, Defendants referred the Court to Macias v. City of Clovis, No. 1:13-CV-01819-BAM, 2015 WL 7282841 (E.D. Cal. Nov. 18, 2015). Macias involved a discovery request by the plaintiff in a civil rights action for disclosure of “the personnel files of each of the defendant officers including documents containing social security numbers, dates of birth, drivers' license numbers, home addresses, financial and credit histories, resumes, medical and psychological information.” Id. at *2. The personnel files also included “employment applications, background investigations, reassignment requests, personal history statements, oaths of office, polygraph questionnaires, performance evaluations, resignation letters, and affidavits of psychological screenings all generated as part of the hire process at the Clovis Police Department.” Id. The District Court balanced the public and private interests and concluded “the balance tips in favor of ordering disclosure subject to a protective order.” Id. at *8. Thus, the documents would be disclosed to the plaintiff, but “in light of the institutional concerns articulated by [d]efendants and the risks that the indiscriminate public disclosure poses to police department operations and officer safety,” the documents “will not be available for public dissemination.” Id.

*5 Macias involved a discovery request for specific officer personnel files containing a variety of sensitive information. Id. at *2. If this case presented a similar request for disclosure of sensitive personal information (e.g., social security numbers, home addresses or employment applications), Macias would support Defendants' argument against public disclosure. But unlike Macias, Defendants seek to redact employee names from every document at issue regardless of whether the document contains sensitive or personnel information. See, e.g., Dkt. No. 737 at 22 (citing disputed SDSO Notes 120522 – “Sergeant REDACTED working on a staff study to convert a holding cell into sobering/safety cell and into holding cell”). Macias does not support the blanket redactions of all employee names irrespective of the documents at issue. The motion to maintain confidentiality of employee names is DENIED.

III.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, Defendants' motion to maintain confidentiality [Dkt. No. 724] is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. Rulings as to specific documents or document categories are set forth in the attached chart, which was submitted by the parties (Dkt. No. 737 at 12-33) and wherein the Court has replaced the “Outcome” column with its rulings. The parties' motions to seal [Dkt. Nos. 726, 738] are GRANTED for the reasons stated on the record.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Footnotes

The relevant factors in this balancing analysis are: “(1) whether disclosure will violate any privacy interests; (2) whether the information is being sought for a legitimate purpose or for an improper purpose; (3) whether disclosure of the information will cause a party embarrassment; (4) whether confidentiality is being sought over information important to public health and safety; (5) whether the sharing of information among litigants will promote fairness and efficiency; (6) whether a party benefitting from the order of confidentiality is a public entity or official; and (7) whether the case involves issues important to the public.” Id. at 424 n.5 (citing Glenmede Trust Co. v. Thompson, 56 F.3d 476, 483 (3d Cir. 1995)).

Defendants cite authority applying the Freedom of Information Act's exemption from disclosure for “personnel and medical files and similar files the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(6). This exemption applies where there is “some nontrivial privacy interest in nondisclosure,” and “[a] showing that the interest is more than de minimis will suffice.” Cameranesi v. United States Dep't of Def., 856 F.3d 626, 637-38 (9th Cir. 2017). However, Defendants provide no authority for the proposition that this statutory exemption provides the appropriate standard for evaluating whether they have established “particularized harm” sufficient to make a showing of good cause for a protective order under Rule 26(c).