Commonwealth v. Suarez-Irizzary

Commonwealth v. Suarez-Irizzary

2010 WL 5312257 (Pa. Ct. Comm. Pleas 2010)

August 6, 2010

Charles, Bradford H., Judge

Summary

The court accepted the Commonwealth's use of Google Earth technology to measure the distance between the defendant's drug transaction and a school, which was used to implicate the school zone sentencing enhancement. Detective Walton testified about his familiarity with the Google Earth system and his independent verification of its accuracy, and the defendant had ample opportunity to challenge the accuracy of the measurement. The court overruled the defendant's objection and accepted the Commonwealth's Google Earth measurement.

Commonwealth

v.

Suarez-Irizzary

v.

Suarez-Irizzary

Nos. CP-38-CR-1204-2009, 1206-2009, 1207-2009, and 1217-2009

Court of Common Pleas of Pennsylvania, Lebanon County

August 06, 2010

Counsel

Nichole Eisenhart, for Commonwealth.Allen Welch, for defendant.

Charles, Bradford H., Judge

Opinion

As technology increases, the law must keep pace. When maps were first created, they represented a cartographer's “best estimate” of where things were located. Since then, measuring wheels, odometers, airplane photography and now global satellite imaging have moved cartography from the realm of human estimating to satellite-verified pinpoint accuracy. When the legal system needs to establish distance with precision, it should not eschew the accuracy that technology now affords in favor of more flawed and primitive means of measurement.

In this case, a dispute has arisen with respect to whether the situs of the defendant's drug transaction was within 1,000 feet of a school so as to implicate the socalled “school zone sentencing enhancement.” The Commonwealth asks us to accept a distance measurement that the Commonwealth obtained using a computer program called “Google Earth”. The defendant challenges the Commonwealth's ability to authenticate the “Google Earth” measurements. Stripped to its essence, the defendant claims that police should have undertaken a physical measurement instead of relying upon a computer-based satellite imaging system.

*109 The issue before us is one of first impression within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Based upon guidance we have gleaned from other jurisdictions, established general precedent regarding authentication, and our own commonsense analysis, we will uphold the Commonwealth's request to establish school zone applicability using Google Earth.

I. FACTS

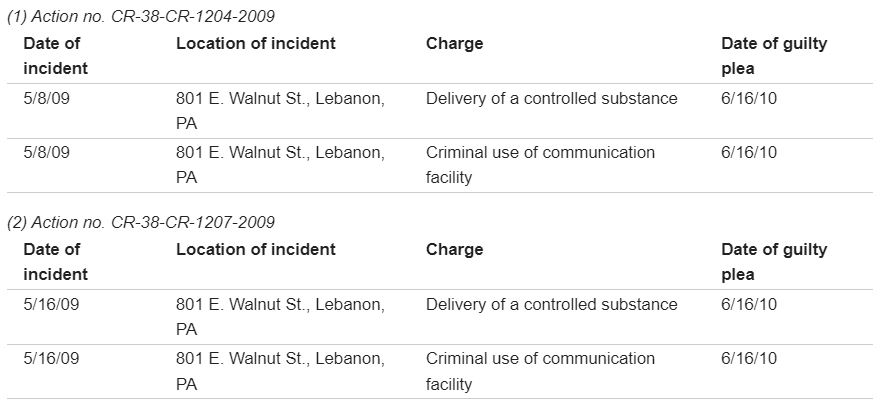

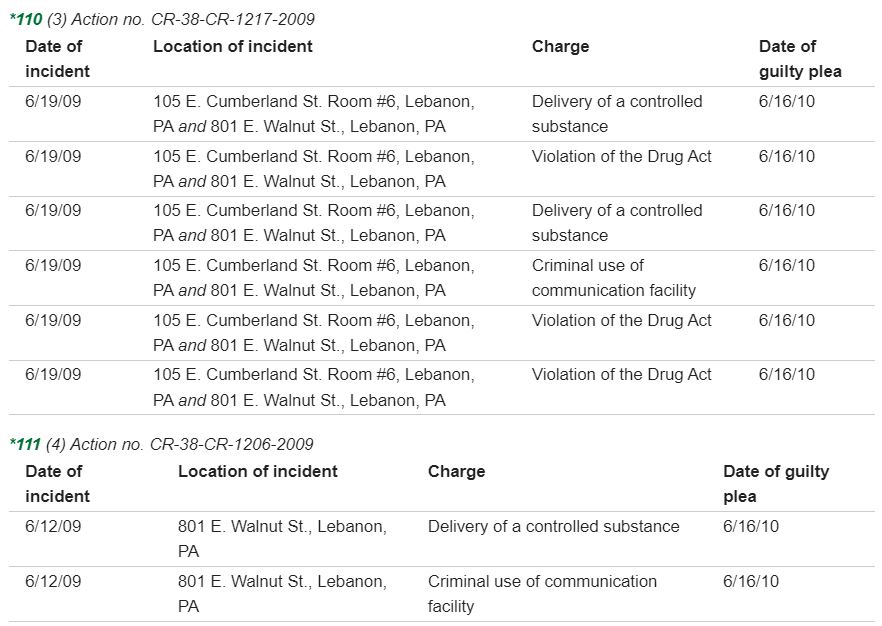

The defendant was charged on four separate action numbers as enacted in the following charts:

Throughout the pendency of the defendant's prosecution, the Commonwealth consistently took the position that the defendant's delivery occurred within 1,000 feet of a school. When the defendant entered a plea of guilty on May 3, 2010, he would not acknowledge in his plea that the drug delivery occurred within a school zone. Rather, he asked that the applicability of the school zone enhancement be decided by the sentencing judge.

On June 16, 2010, the defendant was called before us for sentencing. Prior to actually sentencing the defendant, a brief hering was conducted regarding applicability of the school zone enhancement. At this hearing, the Commonwealth produced Detective William Walton of the Lebanon County Drug Task Force. Detective Walton testified that he utilized a computer program named “Google Earth” in order to determine that the defendant's drug delivery occurred within 1,000 feet of a school. Detective Walton testified that he was familiar with the Google Earth computer program and that he had utilized that tool to determine distance on multiple occasions in the past. Detective Walton told us that before he began using Google Earth to determine distance, he verified its accuracy by physically measuring a distance between *112 two known points and then using Google Earth to calculate the same distance. Detective Walton testified that Google Earth's measurement was within one foot of the one he physically determined.

The defendant did not question the manner in which Detective Walton used the Google Earth system or that the Google Earth calculation resulted in a difference between the drug delivery and a school of less than 1,000 feet. However, the defendant vigorously challenged the authenticity of the Google Earth system. The defendant pointed out that Detective Walton played no part in setting up the satellite imaging system or the Google Earth computer program that relied upon it. Without such evidence, the defendant argued that we should simply disregard Detective Walton's determination that his drug delivery occurred within 1,000 feet of a school zone.

Following the brief sentencing hearing, we asked both parties to submit briefs with respect to the Google Earth authenticity issue. We have received those briefs. The issue of the Commonwealth's reliance upon Google Earth is now before us for disposition.

II. DISCUSSION

Authentication of evidence is addressed by the Pennsylvania Rules of Evidence. Pa.R.E. 901(a) states that the requirement of authentication “is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the matter in question is what its proponent claims.” Pa R.E. 901(a). Rule 901 regarding authentication contains a specific provision dealing with authentication of a “process of system.” Pa.R.E. 901(b)(9) permits authentication by “evidence describing a process or system used to produce *113 a result and showing that the process or system produces an accurate result.”

To our knowledge, Pennsylvania's appellate courts have not yet directly addressed the method by which a computer satellite imaging system can be authenticated. However, in Commonwealth v. Serge, 586 Pa. 671, 896 A.2d 1170 (2006), our Supreme Court did discuss authentication of a computer generated recreation of a crime scene. The court determined that a three-prong test should be used. That test requires:

(1) Some evidence to authenticate the accuracy of the computer imaging;

(2) Relevance; and

(3) That the probative value of the computer imaging outweighs its prejudice.

In pre-internet days, the admissibility of maps was discussed on occasion by our appellate courts. “In determining the admissibility of maps and diagrams, much must be left to the discretion of the trial judge.” Albig v. Municipal Authority of Westmoreland County, 348 Pa. Super. 505, 520, 502 A.2d 658, 666 (1985), citing Jones v. Spidle, 446 Pa. 103, 286 A.2d 366 (1971). “Unofficial maps are usually admissible as evidence when verified by the testimony of a witness who has personal knowledge of their accuracy.” Albig supra at 520, 502 A.2d at 666. The key to authenticating maps is proof of their accuracy, reliability, completeness and fairness. 44 Am.Jur. Proof of Facts Second 707 (Foundation for admission of maps, diagrams or charts, section 1). From a very general perspective, the person who prepared a map or diagram need not be present in court so long as the *114 witness can testify that the diagram fairly and accurately portrays relevant information. 3 Wharton's Criminal Evidence § 16:24 (15th edition).

While Pennsylvania has not directly addressed use of satellite imaging systems to determine distance, other states have done so. Interestingly, most of the cases we found that addressed satellite imaging were presented within the context of a “school zone” dispute similar to the one now before us.

In Commonwealth v. Whitlock, 906 N.E. 2d 995 (Mass. App. 2009), the Commonwealth of Massachusetts sought to prove that a drug sale occurred within 1,000 feet of a school. The Commonwealth presented testimony from a police captain who used a computer program called “Arcview” to determine the distance between the school and the sale. The captain testified that he verified the accuracy of Arcview by comparing the Arcview measurement between two known points with a measurement he personally conducted using a measuring wheel. The court declared that this type of “calibration” was sufficient to support admissibility of the Arcview measurement. The court stated: “In each case where a witness testifies that he used a measuring tool to determine a distance, the relevant question is not whether the testimony is hearsay, but whether the foundation was sufficient for introduction of the observed result.” Id. at 1,000.

In State v. Polanco, 797 A.2d 523 (Conn. App. 2002), the state sought to use a computer-generated map to prove that cocaine was seized within 1,500 feet of a school. The defendant objected to the map based upon lack of foundation and complained that no one established the *115 accuracy of the computer GPS system to create the map. The prosecutor called a geographic information systems technician to describe the map's creation and use. This witness testified that he routinely generated distance information using the GPS system. The court permitted the admission of the computer-generated map and stated: “More specific testimony concerning the underlying technology was unnecessary, and any remaining doubt as to the reliability of that technology went to the weight to be given to the map, not its admissibility.” Id. at 534.

In State v. Franklin, 843 N.E. 2d 1267 (Ohio App.3d, 2005), the prosecution sought to prove that a drug sale occurred within 1,000 feet of a school. To do so, the prosecution proffered a geographic information system specialist who described global imaging software that he used to measure the distance between the drug sale and the school. The defendant argued that the global imaging software must be supported by expert testimony. The Ohio appellate court disagreed. As part of its reasoning, the court emphasized that the defendant had been given notice about the school zone distance and the prosecutor's methodology of calculating that distance well in advance of trial. The court stated that the defendant therefore had the opportunity to conduct his own measurements in order to refute the state's computer-generated calculations.

In State v. Young, 902 So.2d 461 (La. App. 2005), a police officer testified at trial that a drug sale occurred “approximately” 150 feet from a school. The court testified that the police officer's mere estimation of distance, without more, was insufficient to establish that the drug sale occurred within Louisiana's 1,000 foot school zone.*116 On appeal, the prosecution attached maps and measurements generated by the computer program “Map Quest” to verify that the drug sale did in fact occur within the school zone. The prosecution asked the appellate court to take judicial notice of the measurements derived from “Map Quest”. The Louisiana appellate court refused to do so and determined that some supporting testimony would be needed in order to accept the Map Quest measurements.

As we sift through all of the above, we reach the following conclusions with respect to the admissibility of computer-generated satellite imaging distance calculations:

(1) Courts should not take judicial notice of computer-generated satellite maps.

(2) Authenticating evidence will be required before computer-generated satellite-based distance calculations are admitted in evidence.

(3) Neither expert testimony nor testimony from those who created the satellite imaging system are necessary in order to authenticate maps or distances derived from the use of the satellite mapping system.

(4) Computer-generated determinations of distance can be authenticated when an individual testifies that he/she verified the accuracy of the computer program by comparing a computer-generated distance between two known points with an independently determined calculation of the distance between the same two points.

(5) In order to prevent undue prejudice from the use of computer-generated satellite-based imaging systems, the Commonwealth must produce the identity of the *117 imaging system and the results of its usage to the defendant sufficiently in advance of its proffered use that the defendant can make independent calculations and/or dispute the accuracy of the system.

III. CONCLUSION

Based upon the legal conclusions we have derived from our research as outlined above, we determine that the Commonwealth's use of the Google Earth technology was properly authenticated when Detective Walton testified about his familiarity with the Google Earth system and his independent verification of Google Earth's accuracy using two known points that Detective Walton himself measured. In addition, it was plainly apparent to us that the defendant was well aware in advance of sentencing that the Commonwealth intended to produce a distance measurement calculated using Google Earth. The defendant therefore had ample opportunity to make his own distance calculations and/or challenge th accuracy of Google Earth.

Based largely upon these two factual findings, we overrule the defendant's objection to the Commonwealth's use of Google Earth technology. We will accept the Commonwealth's Google Earth measurement at a rescheduled sentencing hearing that we will establish via an order that we will simultaneously enter.