Townhouse Restaurant of Oviedo v. NuCO2

Townhouse Restaurant of Oviedo v. NuCO2

2020 WL 4923732 (S.D. Fla. 2020)

June 24, 2020

Maynard, Shaniek M., United States Magistrate Judge

Summary

The Plaintiffs filed a Motion to Compel the Defendant to produce certain documents. The Court conducted an in camera review of the documents and granted the Plaintiffs' Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment B and Attachment D. The Defendant must produce both the exemplar documents and all comparable documents within ten (10) days of this Order. The Defendant also provided the Court with five additional documents—with attachments—that were inadvertently omitted from the first sample.

TOWNHOUSE RESTAURANT OF OVIEDO, INC. AND ESTERO BAY HOTEL CO., Plaintiffs,

v.

NuCO2, LLC, Defendant

v.

NuCO2, LLC, Defendant

CASE NO. 19-14085-CIV-ROSENBERG/MAYNARD

United States District Court, S.D. Florida

Entered on FLSD Docket June 24, 2020

Counsel

E. Michelle Drake, Pro Hac Vice, Joseph C. Hashmall, Pro Hac Vice, Berger Montague PC, Minneapolis, MN, Garrett Owens, Pro Hac Vice, Nicholas W. Armstrong, Pro Hac Vice, Price Armstrong LLC, Taylor C. Bartlett, Pro Hac Vice, W. Lewis Garrison, Jr., Pro Hac Vice, Heninger Garrison Davis, LLC, Birmingham, AL, Anthony J. Garcia, AG Law, P.A., Tampa, FL, for Plaintiff Townhouse Restaurant of Oviedo, Inc.Anthony J. Garcia, AG Law, P.A., Tampa, FL, E. Michelle Drake, Pro Hac Vice, Joseph C. Hashmall, Pro Hac Vice, Berger Montague PC, Minneapolis, MN, Nicholas W. Armstrong, Pro Hac Vice, Price Armstrong, LLC, Taylor C. Bartlett, Pro Hac Vice, W. Lewis Garrison, Jr., Pro Hac Vice, Heninger Garrison Davis, LLC, Birmingham, AL, for Plaintiff FL Estero Bay Hotel, Co.

Clement Ryan Reetz, David Axelman, Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP, Miami, FL, Kenneth J. Mallin, Pro Hac Vice, LaDawn L. Burnett, Pro Hac Vice, Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP, St. Louis, MO, Zina Gabsi, Chase Law & Associates, P.A., Miami Beach, FL, for Defendant.

Maynard, Shaniek M., United States Magistrate Judge

ORDER ON PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO COMPEL AND FOR SANCTIONS (DE 85)

*1 THIS CAUSE comes before this Court upon the above Motion. Following a hearing held on May 4, 2020, the undersigned directed the parties orally, and in the Order Memorializing Hearing, to select approximately 300 exemplar emails, plus attachments, from Defendant's privilege logs for in camera review. DE 91. On May 15, 2020, Defendant provided exemplar emails and accompanying attachments selected by both parties. This Court has considered the emails and attachments.[1] Having reviewed the materials submitted for in camera inspection, as well as the Motion, Response, and relevant case law, the undersigned resolves Plaintiffs’ Motion as follows.

BACKGROUND

Plaintiffs Townhouse Restaurant of Oviedo, Inc. and Estero Bay Hotel Co. (collectively “Plaintiffs”) filed a class action complaint against Defendant NuCO2, a beverage carbonation company wholly owned by Praxair, Inc., the largest industrial and medical gases company in North America. The Defendant sells carbon dioxide and related equipment at a fixed price through use of a form contract. The form contract allows the Defendant to charge its customers (who are located nationwide) fuel and energy surcharges and implement “open escalation” price increases to pass-through certain costs the Defendant incurs in providing its goods and services. The Plaintiffs claim the Defendant engaged in deceptive and unfair conduct in connection with these surcharges and price increases. Specifically, the Plaintiffs allege that the additional costs charged to the Defendant's customers are actually a “hidden profit device” and have no relation to any increased costs purportedly incurred by the Defendant.

Since this litigation began, the Defendant has produced approximately five different privilege logs asserting privilege over thousands of emails and attachments. On April 16, 2020, the Plaintiffs filed a Motion to Compel arguing that the privilege logs were deficient in several respects. That motion is now ripe for review.

DISCUSSION

I. The Parties’ Dispute

Defendant argues that most of the disputed documents are wholly irrelevant to the case and therefore not discoverable under Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The remaining documents are protected, Defendant contends, by the attorney-client privilege, the accountant-client privilege, and the confidentiality typically afforded to settlement negotiations. Plaintiffs respond that all the documents at issue are presumably relevant because they were identified through keyword searches using terms agreed upon by both the parties. Further, Plaintiffs say Defendant has not met the elements of the accountant-client privilege for documents withheld on that basis and that courts have not recognized a privilege regarding “settlement negotiations.” Lastly, Plaintiffs argue that attorney-client privilege does not protect emails that contain “mere facts and customer files” or communications that do not involve attorneys or legal staff. The undersigned will address each argument in turn.

II. The Burden of Proof

*2 “The discovery respondent bears the burden of establishing a lack of relevancy or some other basis for resisting production.” Safeco Ins. Co. of Am. v. Weissman, 2018 WL 7046634, at *2 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 5, 2018). The party asserting a privilege has the burden of proving the applicability of that privilege. Commercial Long Trading Corp. v. Scottsdale Ins. Co., 2012 WL 6850675, at *2 (S.D. Fla. Dec. 26, 2012); Bridgewater v. Carnival Corp., 286 F.R.D. 636, 638 (S.D. Fla. 2011). This burden is not met by conclusory claims that a privilege applies. MapleWood Partners, L.P. v. Indian Harbor Ins. Co., 295 F.R.D. 550, 584 (S.D. Fla. 2013). Rather, courts require that a party asserting privilege provide “specific detail as to the content of documents and their authors and recipients ... in order to permit meaningful judicial review of the asserted privilege.” Id. In other words, “[t]he [c]ourt should not have to guess or speculate about the applicability of the privilege, for the party asserting it has the affirmative duty to demonstrate that it applies to each document or communication sought to be disclosed.” Wyndham Vacation Ownership, Inc. et al. v. Reed Hein & Associates, LLC, et al., 2019 WL 9091666, at *7 (M.D. Fla. Dec. 9, 2019) (quoting Purdee v. Pilot Travel Centers, LLC, 2008 WL 11350099, at *1 (S.D. Ga. Feb. 21, 2008) (internal quotations omitted).

To have this burden of proof means that the party asserting a privilege is aware that it must produce specific factual support and legal authority to establish that each element of the specific privilege applies to each communication that they claim is protected from disclosure. Campero USA Corp. v. ADS Foodservice, LLC, 916 F. Supp. 2d 1284, 1293 (S.D. Fla. 2012) (emphasis added). If the party does not provide enough information to establish this, then the claim of privilege fails. MapleWood Partners, L.P., 295 F.R.D. at 584; Bridgewater v. Carnival Corp., 286 F.R.D. at 639.

III. Analysis

A. Relevance

Defendant contends that most of the withheld documents are irrelevant and therefore not discoverable under Rule 26. Plaintiffs responds that these documents are presumably relevant since they contain the parties’ agreed upon search terms. Under the Federal Rules, discovery is very broad. And it was intended to be this way: the adoption of the Federal Rules meant that discovery “no longer need be carried on in the dark.” Hickman v. Taylor, 67 S.Ct. 385, (1946). Although recent amendments to Rule 26(b) have altered the language since Hickman, the governing principle behind discovery—that it is to be a broad, inclusive process designed to facilitate the open exchange of information—remains true to this day. 8 Charles Alan Wright & Arthur R. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure, § 2007 (3d ed. 2020). The text of Rule 26 enables broad discovery stating that “parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case[.]” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(1). But broad as the rule may be, the Court retains the power to limit the extent of discovery if it finds the proposed discovery exceeds the scope allowed under Rule 26(b)(1). Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(2)(C)(iii).

Relevancy is key to determining the proper scope of discovery. To be relevant, the information sought must be “germane, conceivably helpful to the plaintiff, or reasonably calculated to lead to admissible evidence.” Donahay v. Palm Beach Tours & Transp., Inc., 242 F.R.D. 685, 687 (S.D. Fla 2007). Although the disclosed information need not be admissible as evidence, the information must relate to the claims and defenses raised, rather than the general subject matter. Id. While a party cannot prematurely limit discovery by decrying any request as a “fishing expedition,” the information sought must still be relevant to the issue before the court. See Hickman, at 392; Kahn v. United States, 2015 WL 4112081, at *2 (S.D. Fla. July 8, 2015) (stating that discovery requests must be relevant to a party's claim).

*3 The relevancy determination has taken on increased importance given the vast amounts of electronically stored information often involved in civil litigation today. A great deal of communication occurs by email, for example, which has fundamentally altered the discovery process. The sheer volume of emails, attachments, digital files, and electronic data can become a major source of hardship during the discovery process. See The Sedona Conference, The Sedona Conference Best Practices Commentary on The Use of Search & Information Retrieval Methods in E-Discovery, 15 Sedona Conf. J. 217, 228–29 (2017) (discussing the proliferation of e-storage and the challenges such practices pose to litigants). Fortunately, technology offers a remedy in the form of keyword searches that may be used to locate responsive documents and limit excessive discovery. Id. Although keyword searches help eliminate problems, they can create issues of their own as well. One problem with keyword searches is their potential to be over or underinclusive. The degree to which the search terms either exclude or include relevant documents can have an immense effect on the number of documents produced. See L-3 Commc'ns Corp. v. Sparton Corp., 313 F.R.D 661, 666 (M.D. Fla. 2015) (discussing challenges presented by the search term process and the factors that create accurate search terms).

Having conducted an in camera review, this Court agrees with Defendant that the vast majority of the disputed documents are entirely irrelevant to this case. If in fact they emerged from the use of agreed upon search terms, perhaps those terms needed to be further narrowed or only applied to information held by certain custodians or divisions within NuCO2. As it stands, most of the documents submitted relate to issues regarding state or local regulatory requirements, safety standards and permitting processes, mergers and acquisitions of NuCO2 or its clients, and other prospective business opportunities. These subject matters are not germane to the case, helpful to the Plaintiffs or reasonably likely to lead to admissible evidence. Because these documents are irrelevant, Defendant is not required to produce them. Thus, Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the documents listed in Attachment A is denied on relevancy grounds.

B. Accountant-Client Privilege

The next category of documents involves three emails and accompanying attachments that NuCO2 claims are protected by the accountant-client privilege. Under Florida law, confidential communications between an accountant and client are protected when the communications involved were made for the purpose of accounting services:

A client has the privilege to refuse to disclose, and to prevent any other person from disclosing, the contents of confidential communications with an accountant when such other person learned of the communications because they were made in the rendition of accounting services to the client. This privilege includes other confidential information obtained by the accountant from the client for the purpose of rendering accounting advice.

Fla. Stat. § 90.5055. “A communication between an accountant and the accountant's client is confidential if it is not intended to be disclosed to third persons other than: (1) those to whom disclosure is in furtherance of the rendition of accounting services to the client; and (2) those reasonably necessary for the transmission of the communication.” TIC Park Ctr. 9, LLC v. Cabot, 2017 WL 9988745, at *9 (S.D. Fla. June 9, 2017) (citing Fla. Stat. § 90.5055(1)(c)).

This Court need not extensively discuss the accountant-client privilege because it does not apply to any of the documents submitted for this Court's review. Defendant submitted three documents that it claims are confidential accountant-client advice: NuCO2_Priv_932, NuCO2_Priv_934, and NuCO2_Priv_968. The first two documents relate to technical issues NuCO2 experienced with its automatic billing technology. There is no advice from an accountant involved. The third document includes some accounting advice, but NuCO2 is sharing that advice with a customer so it clearly was not meant to be confidential and kept from disclosure to third parties. Thus, these emails and their accompanying attachments are not protected by the accountant-client privilege. NuCO2_Priv_932, NuCO2_Priv_934, and NuCO2_Priv_968 are included in Attachment A, however, because they are not relevant to the pending litigation. As a result, the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel NuCO2_Priv_932, NuCO2_Priv_934, and NuCO2_Priv_968 is denied on relevancy grounds.

*4 Since none of the documents NuCO2 claimed were protected by the accountant-client privilege actually warrant such protection, the Court is concerned that other documents are being improperly withheld on this basis. Consequently, the Defendant is instructed to re-review any document withheld based on the accountant-client privilege to ensure that it meets all of the legal requirements. Any document previously withheld under the accountant-client privilege that is relevant and does not meet the requirements of this privilege must be turned over to the Plaintiffs within ten (10) days of this Order.

C. Settlement Negotiations

NuCO2 withholds several documents on the basis that they reveal confidential “settlement negotiations.” In support, NuCO2 relies on Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Chiles Power Supply, Inc., 332 F.3d 976, 980 (6th Cir. 2003), in which the Sixth Circuit held that communications made in furtherance of settlement negotiations are privileged and protected from discovery by litigants in another action. Id. Goodyear is not binding on this Court, however. Indeed, courts in this circuit have rejected the argument that settlement agreements have special protection from discovery. See Kadiyala v. Pupke, 2019 WL 3752654 (S.D. Fla. Aug. 8, 2019) (Matthewman, J.) (reviewing cases and finding no privilege protecting settlement agreements from disclosure); United States ex rel. Cleveland Constr., Inc. v. Stellar Grp., Inc., 2017 WL 11460973, at *1 (M.D. Ga. Oct. 23, 2017) (declining to “invent” a settlement agreements privilege); Jeld-Wen, Inc. v. Nebula Glass Intern., Inc., 2007 WL 1526649, at *3 (S.D. Fla. May 22, 2007) (Torres, J.) (noting that there is “nothing magical” about settlement agreements and no binding or persuasive authority in the Eleventh Circuit instructing otherwise).

The undersigned rejected the idea of a settlement agreement privilege in Silver Streak Trailer Co., LLC v. Thor Indus., Inc., 2018 WL 8367073, at *7 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 15, 2018):

Confidentiality and relevancy considerations are the typical barriers to permitting discovery of settlement agreements. Virtual Studios, Inc. v. Royalty Carpet Mills, Inc., 2013 WL 12090122, at *4 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 23, 2013). However, “[d]espite the salutary purposes of preserving confidentiality to encourage settlements, under appropriate circumstances courts have the authority to encroach upon such agreements.” Gutter v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 2001 WL 36086590, at *1 (S.D. Fla. Jan. 31, 2001). Even Federal Rule of Evidence 408, which limits the admissibility of settlement negotiations, “does not create a settlement privilege for purposes of discovery or make settlement agreements and negotiations per se undiscoverable.” Kipperman v. Onex Corp., 2008 WL 1902227, at *9 (N.D. Ga. Apr. 25, 2008). The undersigned recognizes the interests third parties have in the confidentiality of settlement agreements, but litigants cannot shield settlement agreements from discovery solely based on confidentiality if the agreement is relevant to the action, or likely to lead to relevant evidence. Gutter, 2001 WL 36086590, at *1; Channelmark Corp. v. Destination Prod. Int'l, Inc., 2000 WL 968818, at *2 (N.D. Ill, July 7, 2000).

In this circuit, the caselaw makes clear that the touchstone for whether settlement agreements must be disclosed is relevance. Virtual Studios, Inc. v. Royalty Carpet Mills, Inc., 2013 WL 12090122, at *4 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 23, 2013); Mohamed v. Columbia Palms W. Hosp. P'ship, 2006 WL 8435429, at *4 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 30, 2006); Norton v. Bank of Am., N.A., 2006 WL 8432180, at *9-10 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 27, 2006). Consequently, NuCO2 may not withhold settlement documents that are relevant to the litigation. A list of relevant, non-privileged documents previously withheld as settlement negotiations is found at Attachment B. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the documents listed in Attachment B is granted. These documents must be turned over to the Plaintiffs within ten (10) days of this Order. The interest in confidentiality as to these documents may be adequately addressed by the stipulated protective order at docket entry 38.

*5 NuCO2 is not required to turn over settlement documents that are irrelevant or otherwise privileged. Settlement documents that are irrelevant are listed in Attachment A and Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel them is denied. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel is also denied as to settlement documents that are relevant but protected by the attorney-client privilege. Attorney-client privilege documents are discussed below.

D. Attorney-Client Privilege

In federal court, federal common law typically governs the application of attorney-client privilege. Fed.R. Evid. 501. When a federal court is sitting in diversity jurisdiction, however, state law governs. Id.; In re 3M Combat Arms Earplug Prod. Liab. Litig., 2020 WL 1321522, at *4 (N.D. Fla. Mar. 20, 2020); Bivins v. Rogers, 207 F. Supp. 3d 1321, 1324 (S.D. Fla. 2016). The parties are before this Court by virtue of its diversity jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1332(d). Because Florida law provides the rule of decision, Florida law determines the applicability of attorney-client privilege. See Burrow v. Forjas Taurus S.A., 334 F. Supp. 3d. 1222, 1233 (S.D. Fla. 2018) (“State law governs the application of the attorney-client privilege in a federal diversity action.”).

Under Florida law, “[a] client has a privilege to refuse to disclose, and to prevent any other person from disclosing, the contents of confidential communications when such other person learned of the communications because they were made in rendition of legal series to the client.” Fla. Stat. § 90.502(2) (2019). Stated more succinctly by the Florida Supreme Court, attorney-client privilege applies to “confidential communications made in the rendition of legal services to the client.” Burrow, 334 F. Supp. 3d at 1233 (citation omitted). “A communication between lawyer and client is confidential if it's not intended to be disclosed to third persons other than (1) those to whom disclosure is in furtherance of the rendition of legal services to the client[,] [and] (2) those reasonably necessary for the transmission of the communication.” Fla Stat. § 90.502(1)(c).

The application of attorney-client privilege requires the weighing of conflicting policy considerations. On the one hand, the underlying purpose of the attorney-client privilege is to encourage clients to communicate openly with their attorneys. In re Abilify (Aripiprazole) Product Liability Litigation, 2017 WL 6757558, *2 (N.D. Fla. Dec. 29, 2017). On the other hand, attorney-client privilege obstructs the truth-seeking process and contravenes the fundamental principle that the public has the right to view the evidence. See MapleWood Partners, L.P., 295 F.R.D. at 583 (discussing the competing policy concerns raised by attorney-client privilege). This tension—between encouraging transparency between counselor and client and promoting the truth-seeking inquiry of the adversarial process—is heightened when the client asserting the privilege is a corporation.

When the client is a corporate entity, there is heightened risk that the attorney-client privilege will be used to hide information. Burrow, 334 F. Supp. 3d at 1223. Standard corporate email practices—undoubtedly guided by the fallacious notion that a paragraph or label claiming privilege makes it so—encourage the inclusion of in-house counsel in communications that do not pertain to legal advice or srvices. This potential for abuse has led the Florida Supreme Court to provide further guidance for the application of attorney-client privilege in the corporate context: Corporate clients’ claims of attorney-client privilege are subject to heightened scrutiny. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Deason, 632 So.2d 1377, 1383 (Fla. 1994). When the party asserting the privilege is a corporation, it bears the burden of proving that “the communication would not have been made but for the contemplation of legal services; ... the content of the communication relates to the legal services being rendered; and the communication is not disseminated beyond those persons who, because of the corporate structure, need to know its contents.” Preferred Care Partners Holding Corp. v. Humana, 258 F.R.D. 684 (S.D. Fla. 2009) (quoting 1550 Brickell Assocs. v. Q.B.E. Ins. Co., 253 F.R.D. 697, 699 (S.D. Fla. 2008)).

*6 Plaintiffs complain that Defendant wrongfully asserts attorney-client privilege over emails that do not involve lawyers or legal staff. DE 85 at 5 (complaining that “[m]ore than 29% of the documents NuCO2 withheld do not contain an attorney or attorney-staff on them”). Plaintiffs insist that if attorneys do not participate in an email communication, that email cannot be protected by the attorney-client privilege. Plaintiffs’ position is incorrect. It is not necessary for an attorney or legal staff to be a party to a communication to make it privileged. While the lack of any attorney involvement may be a factor tending to weigh against a finding of privilege, “[t]he ultimate touchstone for application of the privilege ... is whether the communication revealed advice from, or a request for advice made to, an attorney in some fashion.” United States v. Davita, Inc., 301 F.R.D. 676, 682 (M.D. Ga. 2014). Just as the lack of an attorney on an email does not necessarily render that email discoverable, an attorney's participation on the email chain does not necessarily establish privilege either. See Burrow, 334 F. Supp. 3d. at 1236 (stating that a communication is not privileged by virtue of an attorney's presence). “Defendants must show, irrespective of whether one or [any] lawyer[ ] sent or received the communication, that the communication was confidential and that the primary purpose of the communication was to relay, request, or transmit legal advice.” Id. The identity of the sender or recipient is not the important consideration, what is important is the subject matter of the communication and whether it reveals legal services or advice. If two business employees exchanged emails concerning the collection of documents for the purpose of requesting legal advice, such a communication would be privileged despite no lawyers being involved. Conversely, if in-house counsel sent a business employee an email containing his or her feedback on the effectiveness of a recent marketing strategy, that email would not magically become privileged because it was sent by in-house counsel. In re Denture Cream Products Liability Litigation, 2012 WL 5057844, *10 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2012). Regardless of whether a communications’ participants include lawyers, the party asserting attorney-client privilege carries the burden of showing that the primary purpose of the communication in question was to obtain legal advice. Preferred Care Partners, 258 F.R.D. at 689.

Most of the emails NuCO2 refuses to disclose are in fact protected by the attorney-client privilege. The privileged emails largely involve in-house counsel providing legal advice to NuCO2 managers or responding to legal inquiries or concerns. Some of the emails are between NuCO2 managers and employees, and do not involve lawyers or legal staff. Yet, that is not fatal to Defendant's privilege claim. Emails in which employees transmit legal advice received from counsel between themselves or request information from one another in order to seek legal advice remain privileged despite no lawyer being on the email thread. Attachment C lists all documents reviewed in camera that are protected by the attorney-client privilege. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the documents in Attachment C is denied on privilege grounds.

Some of the emails on NuCO2's privilege logs do not meet the elements of the attorney-client privilege, however. Attachment D sets forth the emails and attachments that are not protected by the attorney-client privilege and which must be turned over in this case. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the documents in Attachment D is granted.

As a final point, this Court notes that many of the emails that NuCO2 claims are privileged were transmitted with multiple documents attached. Plaintiffs complain that the attached documents are “mere facts and customer files” that do not become privileged just by being attached to a privileged email communication. This Court agrees with Plaintiffs’ position, generally speaking. See In re Abilify, 2017 WL 6757558 at *7 (“Simply because factual information has been transmitted to an attorney does not make the underlying factual information privileged.”). At the same time, factual information that has been gathered and transmitted by corporate employees to an attorney for the purpose of receiving legal advice may be privileged, even if such information, by itself, would not otherwise be protected from disclosure. Id.

In Upjohn Co. v. United States, 101 S.Ct. 677 (1981), the Supreme Court set out the basic relationship between privileged attorney-client communications and factual information accompanying those communications: “The privilege only protects disclosure of communications; it does not protect disclosure of the underlying facts by those who communicated with the attorney.” Id. at 685. This principle was reiterated by the Florida Supreme Court in Deason, 632 So.2d at 1387. But Deason clarified that even factual information can be withheld when its disclosure would reveal the substance of legal advice. Id. In Deason, counsel sought to depose corporate managers of Southern Bell to find out about disciplinary actions taken against certain employees. The managers had no firsthand knowledge of these issues; their only knowledge was based on their review of information obtained from their lawyers. The Deason Court explained:

*7 The instant case presents the difficulty of deciphering the communication from the underlying facts. Public Counsel claims that it did not ask the deponents what the company attorneys told them; rather, Public Counsel only asked why the employees were disciplined or what actions of the employees resulted in discipline. Differentiating between these questions is merely a game of semantics. The privileged information which counsel gave to the managers describes the actions of the employees. To answer Public Counsel's questions regarding the specific reasons the employees were or were not disciplined would necessarily require the deponents to reveal the contents of the privileged communication. Public Counsel cannot obtain indirectly through depositions that information which the law does not permit it to obtain directly through disclosure of the written privileged communication. Therefore, Public Counsel and the PSC are restricted from questioning the deponents in a manner that would require them to reveal the content of the communication.

Id. at 1387.

In considering whether documents attached to privileged communications are protected, the Court must first consider whether the content of the attachment is a communication or a fact. See Upjohn, 449 U.S. at 395-96 (the privilege applies only to communications and does not extend to facts). If the attachment contains a communication, the Court must consider whether it evidences a request for legal assistance or the transmission of legal advice. U.S. ex rel. Baklid-Kunz v. Halifax Hosp. Med. Cent., 2012 WL 5415108, *3 (M.D. Fla Nov. 6, 2012). If the attachment contains facts and not communications, the Court must evaluate whether disclosure of the facts would somehow reveal a request for, or the content of, legal advice. See Deason, 632 So.2d at 1387. As Deason explained, Plaintiffs cannot obtain indirectly (through documents attached to privileged emails) that which they could not obtain directly from the privileged communications themselves. Compare Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Ocwen Financial Corp., 2019 WL 1119788, *3 (S.D. Fla. Mar. 12, 2019) (declining to compel disclosure of factual information curated and re-formatted by attorneys for the purpose of providing legal advice), with U.S. ex rel. Baklid-Kunz, 2012 WL 5415108 at *7 (compelling disclosure of factual information that did not reflect legal advice or information transmitted to counsel for the purpose of obtaining legal advice).

With these legal principles in mind, the undersigned reviewed each email and attachment separately to determine whether the attorney-client privilege applies. For purposes of this review, the undersigned refers to the cover email as the “parent” email, each attachment as a “child” document, and the email plus attachments as an email “family.” Where one or some child documents need be treated differently from the parent email in a single email family, Attachment E explains the undersigned's ruling. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the documents in Attachment E is granted in part and denied in part based on the undersigned's specific instructions. Where Attachment E indicates that a document, or a portion thereof, must be turned over, Defendant must do so within ten (10) days of this Order.

E. Sanctions

Plaintiffs also move to sanction Defendant should the Court grant any part of their Motion. Rule 37(a)(5)(A) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides that where a motion to compel is granted, the court must require the party or attorney whose conduct necessitated the motion, or both, “to pay the movant's reasonable expenses incurred in bringing the motion, including attorney's fees.” Rule 37(a)(5)(A). The Rule goes on to state, however, that payment shall not be ordered if the opposing party's nondisclosure was substantially justified. Fed.R.Civ.P. 37(a)(5)(A)(ii). This Court has conducted a thorough review of the documents submitted and determined that the vast majority were properly withheld from disclosure. Therefore, NuCO2's position was substantially justified and the Plaintiffs’ request for sanctions is denied.

CONCLUSION

*8 Accordingly, for the reasons set forth above, it is therefore,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment A is DENIED. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment B is GRANTED. The Defendant shall produce both the exemplar documents in Attachment B and all comparable documents within ten (10) days of this Order. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment C is DENIED. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment D is GRANTED. The Defendant shall produce both the exemplar documents in Attachment D and all comparable documents within ten (10) days of this Order. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel as it relates to documents in Attachment E is GRANTED in part. The Defendant shall produce the exemplar documents as instructed in Attachment E and all comparable documents within ten (10) of this Order. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Compel the remaining documents in Attachment E is otherwise DENIED. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Defendant shall re-review all documents withheld on the basis of accountant-client privilege to ensure that they meet the requirements of the accountant-client privilege. Specifically, any document withheld on the basis of accountant-client privilege must contain confidential communications made by an accountant in rendering accounting services to NuCO2, or confidential information obtained by the accountant from NuCO2 for the purpose of rendering accounting advice. The Defendant shall produce any documents that are relevant and not protected by the accountant-client privilege within ten (10) days of this Order. It is further,

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Plaintiffs’ request for an award of fees and costs incurred in bringing their Motion is DENIED.

DONE AND ORDERED in Chambers at Fort Pierce, Florida, this 24th day of June, 2020.

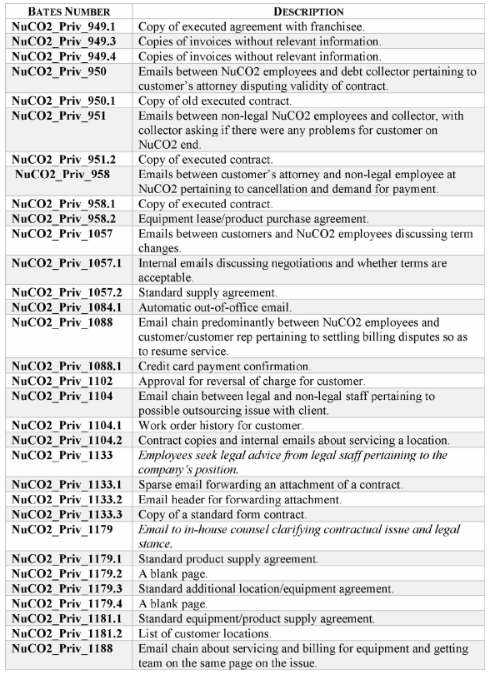

ATTACHMENT A

NOT RELEVANT/DO NOT PRODUCE

Note: The preceding image contains the reference for footnote[1]

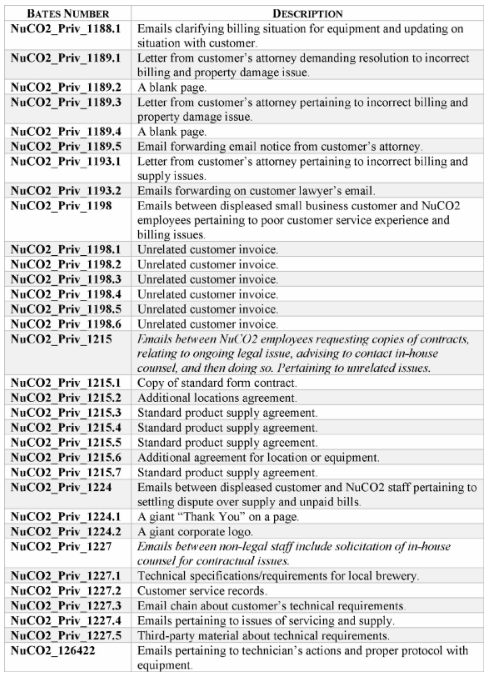

ATTACHMENT B

RELEVANT SETTLEMENT DOCUMENTS / MUST PRODUCE

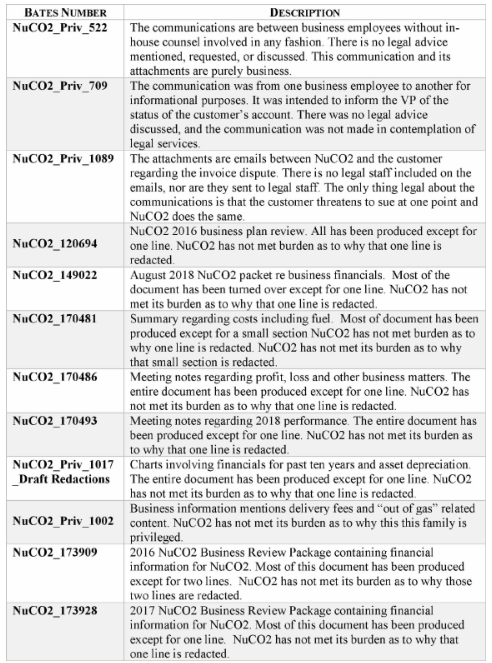

ATTACHMENT C

RELEVANT/PROTECTED BY ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE/ DO NOT PRODUCE

ATTACHMENT D

RELEVANT/NO ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE/ MUST BE PRODUCED

ATTACHMENT E

ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGED IN PART/ PRODUCE AS INSTRUCTED

Footnotes

The Defendant submitted a representative sample of 353 emails to the Court. The majority of these included attached documents, for a total of approximately 992 items for the Court's review. On June 3, 2020, the Defendant provided the Court with five additional documents—with attachments—that were inadvertently omitted from the first sample.

Italics are used in Attachment A to identify documents that may be protected by the attorney-client privilege in addition to being irrelevant.