Cisneros, Lisa J., United States Magistrate Judge

This Document Relates to: ALL ACTIONS

PRETRIAL ORDER NO. 9: ORDER ON ESI PROTOCOL DISPUTES

The parties have filed competing proposed ESI protocols and briefs in support of their proposals. The Court resolves the parties’ disputes below. The final ESI protocol will be entered as a stipulated order after the parties file a final version reflecting the Court’s rulings in this Order.

Where the Court refers to section numbers from the parties’ proposed ESI

protocols, the Court will specify which party’s document it is citing unless the disputed

subject matter is address in the same section in both protocols.

I. DISCUSSION

A. Definitions

1. Definition of “Attachment”

The parties disagree about how to define “attachment,” at least in part as an outgrowth of a larger dispute about whether documents hyperlinked in electronic communications should be treated as “attachments.” The resolution of this issue hinges on the outcome of the parties’ dispute about the treatment of cloud-based documents. As discussed in greater detail below, the Court will not resolve that issue at this juncture. See Part I(J) below. This definition, too, should be revisited in accordance with the eventual resolution of the cloud-stored documents issue.

2. Definition of “Parent-Child”

Plaintiffs’ proposed definition, contained in Section 2(t) of their proposed ESI protocol, shall be adopted as follows: “‘Parent-child’ shall be construed to mean the association between an attachment and its parent Document in a Document family.”

B. Cooperation

The parties disagree over certain introductory language that describes the parties’ obligations to cooperate. The core object of dispute is Uber’s desire to include language from Sedona Principle No. 6 to the effect that “responding parties are best situated to evaluate the procedures, methodologies, and technologies appropriate for search, review, and production of their own ESI[.]” The text on which the parties do not agree is emphasized below:

The Court will not require the parties’ ESI protocol to restate Sedona Principle No.

6, nor will the Court require that the parties adopt the principle in the abstract. See Klein v.

Facebook, Inc., No. 20-cv-08570-LHK (VKD), 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 175738, at *7

(N.D. Cal. Sep. 15, 2021). Nor will the Court adopt Plaintiffs’ additional language in this

section. Instead, the disputed paragraph shall read, in its entirety, as follows: “The Parties

are aware of the importance the Court places on cooperation and commit to cooperate in

good faith throughout this Litigation consistent with this Court’s Guidelines for the

Discovery of ESI and this Court’s Rules of Professional Conduct.”

C. Documents Not “Reasonably Accessible”

Plaintiffs’ proposal contains a paragraph describing a relatively detailed process for meeting and conferring about sources of ESI that the Producing Party determines are not “reasonably accessible,” which includes a seven-day timeframe and a provision for bringing disputes to the Court if meeting and conferring is unsuccessful. Uber omits most of this language and simply says that the parties should meet and confer about such sources. The disputed language is as follows:

Plaintiffs’ proposal is preferable because it provides clearer guidance for resolving these disputes and a defined time period for doing so. The parties shall adopt the language in Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 7.

D. Search Queries and Methodologies

1. Overview of Search Queries and Methodologies

The parties disagree over certain introductory language in Section 8 of their

proposed ESI protocols:

The parties shall adopt Uber’s proposed language for this portion of the protocol, with the following modifications:

The Court strikes the reference to Section [7] because there are other sections of the

ESI Protocol that address aspects of the discovery process that will be appropriate subjects

for meet and confers. The Court also recognizes that terms such as “predictive coding” are sometimes used interchangeably with TAR, though in recent years TAR appears to be the

more commonly used term. See The Sedona Conference, TAR Case Law Primer, Second

Edition, 24 Sedona Conf. J. 1, 7 n.1 (2023). Furthermore, as TAR methodologies evolve,

they are categorized as TAR 1.0, TAR 2.0, and so on. The purpose of the prefatory

language In Section 8 of the ESI Protocol is not to enumerate every topic for negotiation.

Instead, the purpose is to require the parties to cooperate, consistent with the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure and our Court’s guidelines, to determine the search queries and

methodologies that will be used and how ESI discovery will be conducted more generally,

in a manner that satisfies the “reasonable inquiry” under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

26(g)(1).

2. Technology Assisted Review (TAR)

The parties disagree over certain language in the description of the TAR methodology that Uber intends to use. The language on which the parties disagree is emphasized below.

The parties shall adopt Plaintiff’s proposed language in this section.

3. TAR and Search Terms

The parties disagree about whether the dataset to which the TAR methodology is

applied will be pre-filtered with search terms—i.e., whether TAR processing will be

“stacked” with the application of search terms. Plaintiffs request language foreclosing this

approach, while Uber seeks to omit Plaintiffs’ proposed language:

Instead of Plaintiffs’ proposed language, the relevant section of the ESI protocol

shall read as follows: “TAR processing may be ‘stacked’ with the application of search

terms. If search terms are to be applied, the parties shall meet and confer regarding the

proposed search terms. The search terms may be agreed by the parties, or certain search

terms may be ordered by the Court if the parties are unable to reach an agreement.”

4. TAR Sample Set and TAR Training Process

Plaintiffs’ proposal describes a detailed process by which the TAR methodology

will initially be applied to a sample set of documents and the documents will be reviewed and coded for relevance, with input from both parties. See Plaintiffs’ Proposed ESI

Protocol, § 8(a)(3). It then describes a process through which the TAR software will be

trained using the agreed upon, coded sample set. See id. § 8(a)(4). Uber’s proposal omits

any discussion of this subject. Uber, with the support of its expert Maura Grossman,

argues that the training processes described by the Plaintiffs are unnecessary for the TAR

2.0 methodology they will use. See Grossman Decl. (dkt. 262-7) ¶¶ 15–17.

The Court agrees with Uber. TAR 2.0, unlike TAR 1.0, does not require a preliminary training process or a sample set with which to carry out that process, so it is unnecessary for the protocol to include any of Plaintiffs’ proposed language on these subjects. Plaintiffs’ proposed Sections 8(a)(3) and 8(a)(4) shall be omitted.

5. Stopping Criteria

The parties disagree over the language describing the “stopping criteria” that will

dictate when the TAR is paused for validation of the results. The parties’ proposals are as

follows, with key disputed language emphasized:

Plaintiffs’ proposed language provides more definite guidance for the validation process, while Uber’s approach is more vague and therefore more likely to lead to disputes. The parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed language on this topic.

6. Validation—Recall and Richness

The parties disagree over a phrase regarding what information Uber will have to

disclose as part of the TAR validation process:

The parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 8(a)(6)(vii). However, references to “Richness” shall be replaced with the term “Prevalence” in this section and in all other ESI Protocol provisions concerning validation. See, e.g., Grossman Decl. ¶ 24 (describing steps to estimate “recall and prevalence”).

7. Validation—Further Review

Plaintiffs’ proposal sets forth a process through which Plaintiffs will have the opportunity to review documents from the TAR validation sample and independently assess whether the process has accurately coded the documents. Plaintiffs include a provision that “[i]f the recall estimate derived from the validation sample is below 80%” or otherwise is “too limited,” then the parties shall discuss remedial action. Plaintiffs’ Proposed ESI Protocol § 8(a)(6)(x). Uber argues that Plaintiffs’ proposal on this topic would require an excessive degree of transparency and input into Uber’s search processes. They also argue that the benchmarks Plaintiffs set (for example, the 80% figure) are unreasonable and unlikely to be met by any conceivable TAR approach.

The review process that Plaintiffs propose establishes quality-control and qualityassurance procedures to validate Uber’s production and ensure a reasonable production consistent with the requirements of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(g). See Forrest Decl. ¶ 41; Luhana Decl. Ex. 8 (dkt. 261-9) (In re: 3M Combat Arms Earplug Prods. Liability Litig. TAR Protocol). However, some adjustment to the provision that appears to set an 80% recall requirement is needed. The parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed Sections 8(a)(6)(viii)–(x) with this modification to Section 8(a)(6)(x). The following sentences shall be added at the end of Section 8(a)(6)(x):

8. DisclosuresIf the validation protocol leads to an estimate lower than 80%, or even lower than 70%, this lower recall estimate does not necessarily indicate that a review is inadequate. Nor does a recall in the range of 70% to 80% necessarily indicate that a review is adequate; the final determination of the quality of the review will depend on the quantity and nature of the documents that were missed by the review process.

If the Producing Party is identifying responsive ESI, which is not already known to be responsive, using search terms, the Parties will meet and confer about search terms in English and any other languages used in the Producing Party’s documents. Before implementing search terms, the Producing Party will disclose information and meet and confer within seven days of the ESI Protocol being entered, or on a date agreed upon by the parties, regarding the search platform to be used, a list of search terms in the exact form that they will be applied (i.e., as adapted to the operators and syntax of the search platform), significant or common misspellings of the listed search terms in the collection to be searched, including any search term variants identifiable through a Relativity dictionary search with the fuzziness level set to 3, any date filters, or other culling methods. At the same time the Producing Party discloses the search terms, unless the Receiving Party agrees to waive or delay disclosure, the Producing Party shall disclose the unique hits, hits with families, and the total number of documents hit. Within seven days after the Producing Party discloses its list of search terms and related information, the Receiving Party may propose additional or different search terms or culling parameters and may propose a limited number of custodians for whom, across their email and other messages, the Receiving Party requests that no search term pre-culling be used prior to TAR 2.0. At the same time the Receiving Party discloses its proposals, it may request that the Producing Party provide hit reports, and the Producing Party must promptly respond with that information but may also provide other information. The parties must confer within 14 days after the Receiving Party’s proposal to resolve any disputes about the search terms. The parties may agree to extend this deadline, but no extension may be more than 14 days without leave of the Court. Use of search terms shall be validated post-review using comparable methodology and metrics to those set out in Disclosures (a) and (c) above.

E. End-to-End Validation of Defendants’ Search Methodology and Results

Plaintiffs propose parameters for the parties to meet and confer regarding

procedures to validate the effectiveness of Uber’s search methods. Uber objects to the

inclusion of this section and would omit it entirely. But in light of Uber’s obligation under

Rule 26(g) to certify complete production, it is appropriate that Uber demonstrates to

Plaintiffs that it has made a reasonable inquiry as to the completeness of its production. In

light of the anticipated volume and methods of ESI to be searched, Plaintiffs propose a

reasonable process for Uber to do so. Similar language has been included in ESI orders in

other MDLs. See, e.g., TAR Protocol, In re: Volkswagen “Clean Diesel” Marketing, Sales

Practices, and Prods. Liab. Litig., 15-md-02672-CRB, Dkt. 2173 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 7, 2016).

Accordingly, the parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 9, which is as follows:

The Parties shall participate in an iterative and cooperative approach in which the Parties will meet and confer regarding reasonable and appropriate validation procedures and random sampling of Defendants’ Documents (both of relevant and nonrelevant sets and of the entire collection against which search terms were run or TAR or other identification or classification methodology was used), in order to establish that an appropriate level of end-to-end recall (the percentage of responsive Documents in the initial collection before any search terms or TAR or manual review was applied which were classified as responsive after Defendants search, TAR and review processes) has been achieved and ensure that the Defendants’ search, classification and review methodology was effective and that a reasonable percentage of responsive ESI was identified as responsively being omitted.

F. Unsearchable Documents

The parties disagree about the language that should govern documents that cannot be searched through text-based means, such as images, spreadsheets, or videos:

It is more efficient for the Court to direct the parties now regarding unsearchable documents, rather than leaving the issue for a later meet and confer process. Accordingly,

the parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 10.

G. Non-Traditional ESI

Section 10 of Uber’s proposed ESI protocol states that, while the ESI protocol is intended to “address the majority” of ESI handled in this matter, the parties may “come into contact with more complex, non-traditional or legacy data sources, such as ESI from social media, ephemeral messaging systems, collaboration tools, data formats identified on a mobile or handheld device, and modern cloud sources.” Uber’s Proposed ESI Protocol § 10. If that occurred, the parties would agree to “take reasonable efforts to appropriately address the complexities introduced by such ESI.” Plaintiffs’ proposal does not include a comparable provision. Insofar as Uber’s proposed language implies that the listed types of ESI are exempt from the ESI protocol or otherwise due for special treatment, it would leave too many sources of ESI outside the bounds of the protocol—it would create an exception that could swallow the rule. Uber’s proposed Section 10 shall be excluded.

H. Reassessment

Section 11 of Plaintiffs’ proposed ESI protocol provides for the “reassessment” of

search methods after the search process has been completed, if one of the parties or the

Court “perceive[s] the need” to do so. It further notes that “the time, cost, and/or other

resources expended in connection with ineffective methodologies and/or processes shall be

deemed irrelevant to the issues of reasonableness and proportionality for additional efforts

required.” Pls.’ Proposed ESI Protocol § 11. Uber’s proposal does not contain a

comparable section. The Court agrees with Uber that this section is unnecessary.

Moreover, the Court will not predetermine that any issue related to reasonableness or

proportionality is irrelevant. Accordingly, Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 11 shall be

excluded.

I. Deduplication

The parties disagree over whether certain language should appear in their proposed

sections on “deduplication.” The parties’ competing proposals are as follows, with disputed language emphasized:

Plaintiffs’ expert Douglas Forrest attests that the sorting contemplated in the emphasized language above is typical in ESI protocols, and nothing in evidence submitted by Uber addresses this specific issue or contradicts Forrest’s assertion. See Forrest Decl. ¶¶ 74–78 (dkt. 261-7). The parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed language in this section of the ESI Protocol.

J. Cloud Stored Documents

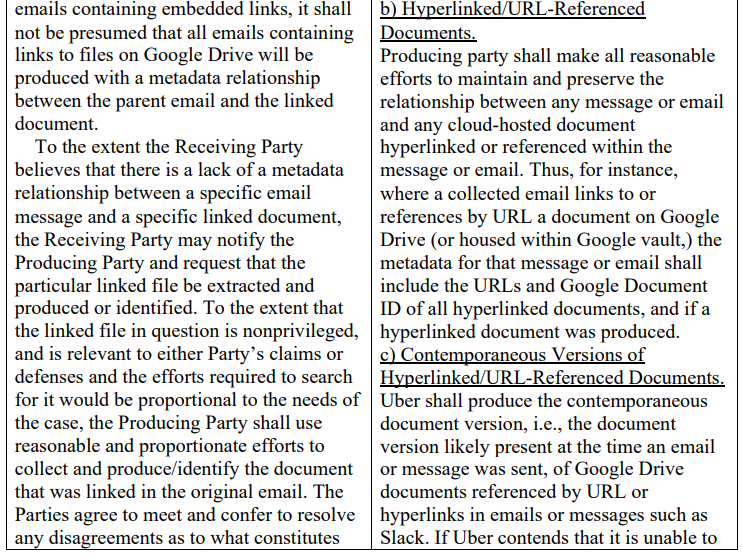

One of the parties’ central areas of dispute is the treatment of cloud-based documents, such as Google Docs, that are incorporated into emails or other communications by hyperlink. In essence, the parties’ competing proposals on this topic reflect disputes over (1) whether the Producing Party will have to identify the metadata associated with the email and hyperlinked documents; (2) whether the Producing Party will have to produce hyperlinked documents along with the communications that link to them; and (3) whether it will have to produce contemporaneous versions of those documents, or simply have to produce whatever the current version is at the time of production. Plaintiffs argue that Uber can and should use a program called MetaSpike to achieve the types of output Plaintiffs want, while Uber argues that MetaSpike is not a feasible or proportional solution, and that the “Google Parser” tool developed by Lighthouse, Uber’s e-discovery vendor, should be used. The proposed language is as follows:

Uber asserts that complying with Plaintiffs’ proposal will not only be unduly expensive, but that existing technology (including MetaSpike) does not permit it to do so. For support, it points to a number of recent ESI protocols that have declined to treat hyperlinked documents and traditional email attachments the same way. Plaintiffs and their expert disagree that their proposal is infeasible, and they point to several other recent MDL ESI protocols that have adopted their basic approach of treating hyperlinked documents as attachments.

This is a difficult, and highly technical, area of dispute. With respect to Plaintiffs’ demand that Uber produce the contemporaneous version of hyperlinked/URL-referenced documents, the evidence that Uber has introduced in support of its position—principally, the declarations of Philip Favro, an e-discovery expert, and Jake Alsobrook, a representative of Uber’s e-discovery vendor—speaks generally about the difficulties of automated production of hyperlinked documents, and particularly old versions of those documents, in the Google Workspace environment. See Favro Decl. (dkt. 262-8); Alsobrook Decl. (dkt. 262-9).

Google Vault is a primary concern because much of Uber’s ESI is located in

Google Vault due to is retention policy. The parties’ declarants agree that Google Vault

provides functionality to enable users to preview and export earlier versions. See Favro

Decl. ¶ 22 (dkt. 262-8); Forrest Decl. ¶ 73 (dkt. 261-7). Favro, however, represents that

Google Vault does not offer a “scalable process” to enable users to capture both the current

version of a document, along with the version contemporaneously exchanged by email.

On the other hand, Forrest states broadly that “Google Vault also has an API that should be explored,” and he proposes that “macro recorders may enable automation and should also

be considered” to the extent that Google Vault requires manual steps to recover a

document. None of Uber’s declarants specifically address whether a macro is feasible to

automate to some extent the process of collecting the contemporaneous versions of

hyperlinked/URL-referenced documents within Google Vault.

Plaintiffs also assert that Uber can access contemporaneous versions of Google documents sent with e-mails by using MetaSpike’s Forensic Email Collector (FEC). ECF No. 261 at 15. Neither Favro, nor Alsobrook, specifically address FEC or the feasibility of deploying it in Uber’s data environment or systems. However, a single paragraph in the declaration of Uber’s counsel, Caitlin E. Grusaukas, states that in connection with negotiations over the JCCP protocol, unnamed counsel for Uber spoke directly with an unnamed person at Metaspike, and “[o]n information and belief, Metaspike confirmed to Uber’s counsel that its FEC software program cannot access items stored in the document retention and archiving system, Google Vault, which Uber uses for Google Workspace data.” Grusaukas Decl. ¶ 6 (dkt. 262-1). The vagueness of this paragraph—and the fact that it is made on information and belief, even though it is one Uber attorney’s description of a conversation had by another Uber attorney—makes it unhelpful. See also Exh. D to Grusaukas Decl. (dkt. 262-5 at 29) (“Metaspike’s documentation indicates that FEC only collects Google Drive documents as well.”). Nor does Plaintiff’s expert clarify the matter. In one statement Forrest seems to concede that FEC is not able to access emails stored in Google Vault. See Forrest Decl. ¶ 72(a). In another Forrest suggests that, depending on a variety of factors, FEC may be deployed at some scale to retrieve emails and linked documents in Google Vault. See id. ¶ 72(c).

In other complex litigation, more detailed information has been requested and

provided to explain why such tools are not feasible. See Declaration of Sam Yang, In re:

Meta Pixel Healthcare Litigation, No. 22-cv-03580-WHO (VKD), Dkt. No. 265 (N.D. Cal.

June 1, 2023); id., Declaration of Jamie Brown, In re: Meta Pixel Healthcare Litigation,

No. 22-cv-03580-WHO (VKD), Dkt. No. 266 (N.D. Cal. June 1, 2023); see also Third Order re Dispute re ESI Protocol, In re: Meta Pixel Healthcare Litigation, No. 22-cv03580-WHO (VKD), Dkt. No. 267 (N.D. Cal. June 2, 2023) (ruling that “the commercially

available tools plaintiffs suggest may be used for automatically collecting links to nonpublic documents have no or very limited utility in Meta’s data environments or systems”).

Accordingly, and in recognition of the challenging nature of hyperlinks, Uber shall direct

an employee with knowledge and expertise regarding Google Vault and Uber’s data and

information systems to investigate in detail the extent to which Google Vault’s API, macro

readers, Metaspike’s FEC or other programs may be useful to automate, to some extent,

the process of collecting the contemporaneous version of the document linked to a Gmail

or other communication within Uber’s systems, whether the email or communication is

stored in Google Vault, or outside. This investigation shall not be limited to documents

referenced by URL or hyperlinks in emails or Google documents stored in Google Vault,

but shall also include other cloud-based messages such as Slack. Uber’s designated

employee may consult with Uber’s e-discovery experts. Likewise, Plaintiffs shall also

more thoroughly investigate these potential solutions.

The parties shall complete their investigation by March 22, 2024, and meet and confer with by March 27, 2024 regarding the hyperlinks issue. The parties should also discuss related portions of the ESI protocol, such as the definition of “attachment,” the metadata categories in Appendix 2, and Sections 1(e), 4, and 14 of Appendix 1. If there is still disagreement on these issues, the parties may submit a discovery letter pursuant to procedure established under Pretrial Order No. 8. If the parties submit a discovery letter to resolve these issues, Uber’s employee designated to conduct its investigation shall submit a declaration supporting its positions, and Plaintiff’s expert(s) and/or e-discovery vendors shall do the same. Uber may also submit declarations from its experts and e-discovery vendors.

K. Continuing Obligations

The parties disagree over certain language in a section regarding the parties’

continuing obligations to meet and confer about discovery. The competing proposals are as follows, with disputed language emphasized:

The parties shall adopt Uber’s proposed language on this topic as modified by the Court. The text of this section shall read: “The parties will continue to meet and confer regarding discovery issues as reasonably necessary and appropriate. This Order does not address or resolve any objections to the Parties' respective discovery requests.”

L. Appendix 1: Production Format[1]

1. Family Relationships

The parties agree on the following text, which shall be included in the ESI Protocol:

Family relationships (be that email, messaging applications, or otherwise) will be maintained in production. Attachments should be consecutively produced with their parent. Objects, documents or files embedded in documents, such as OLE embedded objects (embedded MS Office files, etc.), or images, etc., embedded in RTF files, shall be extracted as separate files and treated as attachments to the parent document. Chats from programs like Slack and HipChat should be produced in families by channel or private message.

Plaintiffs further propose the following language:

“Attachments” shall be interpreted broadly and includes, e.g., traditional email attachments and documents embedded in other documents (e.g., Excel files embedded in PowerPoint files) as well as modern attachments, internal or non-public documents linked, hyperlinked, stubbed or otherwise pointed to within or as part of other ESI (including but not limited to email, messages, comments or posts, or other documents).

The Court will resolve whether to include this text in the ESI protocol after it

decides the disputes raised in Part I(J) above. At that time, the Court will also address the

disputes concerning Metadata Fields and the Production of Family Groups and

Relationships.

2. Redactions

The parties disagree over language governing redactions for relevance made to

documents that otherwise contain relevant information:

The parties shall adapt Plaintiffs’ proposed language in Appendix 1, Section 17.

3. Mobile and Handheld Device Documents and Data

Plaintiffs propose to include a section concerning the production of data on mobile devices. Uber omits any such provision, and—as already discussed—its proposed protocol contains a separate section regarding “non-traditional ESI,” including data from mobile devices. See Part G above. The Court has rejected Uber’s non-traditional ESI language, and it similarly finds that Plaintiffs’ proposed Section 22 of Appendix 1 is reasonable. Accordingly, Appendix 1 shall contain the following language:

If responsive and unique data that can reasonably be extracted and produced in the formats described herein is identified on a mobile or handheld device, that data shall be produced in accordance with the generic provisions of this protocol. To the extent that responsive data identified on a mobile or handheld device is not susceptible to normal production protocols, the Parties will meet and confer to address the identification, production, and production format of any responsive documents and data contained on any mobile or handheld device.

4. Parent-Child Relationships

The parties disagree over certain language relating to the production format of

documents in a parent-child relationship:

The parties shall adopt Plaintiffs’ proposed language in this section of Appendix 1.

M. Appendix 2: Metadata

The parties disagree over the inclusion of certain metadata information, particularly with respect to Google Workspace documents. The Court proposes the following resolution, which the Court believes to be reasonable based on the information before it:

1. Exclude certain fields proposed by Plaintiffs, including (1) “ParticipantPhoneNumbers” and “OwnerPhoneNumbers,” which relate to a service, Google Voice, that Uber does not use; (2) “Rfc822MessageId” and “Account,” which the Alsobrook Declaration, unrebutted by Plaintiffs, states are duplicative of certain other fields; and (3) “LINKGOOGLEDRIVEURLS,” producing which would impose a substantial burden on Uber’s vendor and which appears to serve essentially the same function as another field, “LINKGOOGLEDRIVEDOCUMENTIDS,” the inclusion of which is undisputed. See Ciaramitaro Decl. (dkt. 261-22); Alsobrook Decl. ¶¶ 13–15 (dkt. 262-9).

2. Include the remainder of the metadata fields proposed by Plaintiffs, which

are generated by Google Workspace applications and which, although they may not be

standard information provided by Uber’s vendor, can likely be provided without undue

burden

The Court recognizes that the parties have devoted relatively little attention to the metadata field disputes, either in their briefing or their expert declarations. It may also be the case that the utility of certain metadata fields depends on the outcome of cloud-stored documents disputes. Accordingly, the parties may negotiate the metadata issues when they meet and confer about the cloud-stored documents. But in the absence of complete agreement by the parties on an alternative approach or an otherwise compelling justification, the parties shall adopt the solution proposed above.

II. CONCLUSION

The Court’s rulings on the disputed ESI terms above will be incorporated by the Parties into a final Stipulated and [Proposed] ESI Protocol to be submitted to the Court at the appropriate time. The parties shall comply with the instructions regarding further investigations and meet-and-confer regarding the cloud-stored documents issues, metadata fields, and related provisions of the ESI protocol, including completing their investigations by March 22, 2024, and meeting and conferring by March 27, 2024. See Parts I(J), I(M) above. If any disputes remain after March 27, 2024, the parties shall promptly continue to meet and confer and resolve the outstanding issues by no later than April 3, 2024. If disagreements remain, the parties shall begin the process of preparing a joint letter following the procedures set forth in Pretrial Order No. 8, paragraph 3, and the parties’ joint discovery letter is due April 12, 2024.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Footnote [1] Delete

Footnotes